Yesterday, the Council of Ontario Universities released the results of the Ontario Graduates’ Survey for the class of 2012. This document is a major source of information regarding employment and income for the province’s university graduates. And despite the chipperness of the news release (“the best path to a job is still a university degree”), it actually tells a pretty awful story when you do things like, you know, place it in historical context, and adjust the results to account for inflation.

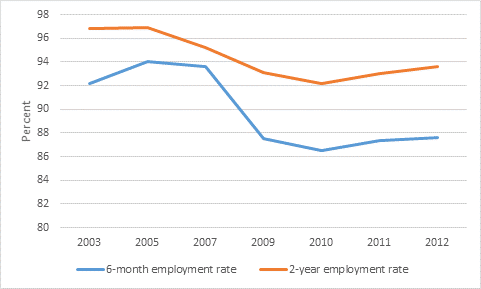

On the employment side, there’s very little to tell here. Graduates got hit with a baseball bat at the start of the recession, and despite modest improvements in the overall economy, their employment rates have yet to resume anything like their former heights.

Figure 1: Employment Rates at 6-Months and 2-Years After Graduation, by Year of Graduating Class, Ontario

Now those numbers aren’t good, but they basically still say that the overwhelming majority of graduates get some kind of job after graduation. The numbers vary by program, of course: in health professions, employment rates at both 6-months and 2-years out are close to 100%; in most other fields (Engineering, Humanities, Computer Science), it’s in the high 80s after six months – it’s lowest in the Physical Sciences (85%) and Agriculture/Biological Sciences (82%).

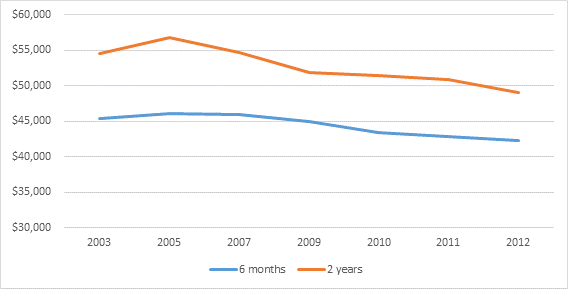

But changes in employment rates are mild compared to what’s been happening with income. Six months after graduation, the graduating class of 2012 had average income 7% below the class of 2005 (the last class to have been entirely surveyed before the 2008 recession). Two years after graduation, it had incomes 14% below the 2005 class.

Figure 2: Average Income of Graduates at 6-Months and 2-Years Out, by Graduating Class, in Real 2013/4* Dollars, Ontario

*For comparability, the 6-month figures are converted into real Jan 2013 dollars in order to match the timing of the survey; similarly, the 2-year figures are converted into June 2014 dollars.

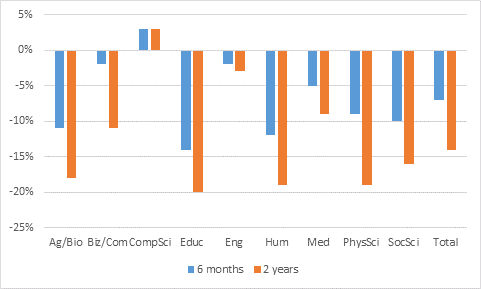

This is not simply the case of incomes stagnating after the recession: incomes have continued to deteriorate long after a return to economic growth. And it’s not restricted to just a few fields of study, either. Of the 25 fields of study this survey tracks, only one (Computer Science) has seen recent graduates’ incomes rise in real terms since 2005. Elsewhere, it’s absolute carnage: education graduates’ incomes are down 20%; Humanities and Physical Sciences down 19%; Agriculture/Biology down 18% (proving once again that, in Canada, the “S” in “STEM” doesn’t really belong, labour market-wise). Even Engineers have seen a real pay cut (albeit by only a modest 3%).

Figure 3: Change in Real Income of Graduates, Class of 2012 vs. Class of 2005, by Time Graduation for Selected Fields of Study

Now, we need to be careful about interpreting this. Certainly, part of this is about the recession having hit Ontario particularly harshly – other provinces may not see the same pattern. And in some fields of study – Education for instance – there are demographic factors at work, too (fewer kids, less need of teachers, etc.). And it’s worth remembering that there has been a huge increase in the number of graduates since 2005, as the double cohort – and later, larger cohorts – moved through the system. This, as I noted back here, was always likely to affect graduate incomes, because it increased competition for graduate jobs (conceivably, it’s also a product of the new, wider intake, which resulted in a small drop in average academic ability).

But whatever the explanation, this is the story universities need to care about. Forget tuition or student debt, neither of which is rising in any significant way. Worry about employment rates. Worry about income. The number one reason students go to university, and the number one reason governments fund universities to the extent they do, is because, traditionally, universities have been the best path to career success. Staying silent about long-term trends, as COU did in yesterday’s release, isn’t helpful, especially if it contributes to a persistent head-in-the-sand unwillingness to proactively tackle the problem. If the positive career narrative disappears, the whole sector is in deep, deep trouble.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Interesting data. My question is how do these university graduate outcomes compare to other post-secondary graduates (eg. community colleges) as well as those who do not go on to post-secondary education at all. If employment and incomes for graduates are trending down for everyone but university degrees have produced the slowest decline, then university may still be the best option. On the other hand, if university graduates have been faring worse than the other two categories I just mentioned, well, then you have an even more serious story that universities may need to care about.

Hi Livio,

It’s a fair point re: relative outcomes (FWIW, my reading of long-term data is that uni results are improving relative to high school but deteriorating relative to college). But “fund us because although we’re doing terribly we’re less awful than the guy next door” works better in economics than it does in politics I think.

Of course one reason that governments fund higher education and encourage a larger and larger number of people to attend is that while they are in education they aren’t in the labour market. If those folks didn’t go to university just imagine what the youth unemployment rate would be!

Also, declines in education salaries are not just about supply and demand. They are the result of political decisions to reduce public sector salaries and decrease numbers of public sector workers. That probably affects employment rates and income for graduates in other fields too, since the public sector is a big employer.

Sort of. I don’t think hiring patterns in education can be divorced from demographics; arguably Ontario waited too long to decrease # of public sector workers in education in face of declining K-12 enrolments. And reductions of public sector pay (or rather, reductions in the rate of growth, don;t think there are many sectors where aggregate pay has actually fallen) has tended to come through attrition. AFAIK *base* rates of pay – what new employees get – has stayed pretty close to inflation in most public-sector white collar occupations (less so in blue collar ones where two-tier contracts have become more common).

i very much enjoy reading your pieces. Thanks . a question- what is the solution to declining grad income levels? You note in the last part of the Basically Awful that ‘until it it tackles …’ so what is the solution?

Also do other provinces do these types of studies?

Most provinces do some kind of grad survey (SK is the basically the only exception) – though they are not usually as frequent or as large as Ontario’s (BC, QC and AB also do it fairly frequently). As to what they should do – hey, I gotta keep some secrets for the consulting business. But paying more attention to transferring transversal skills as well as subject mastery seems like a pretty basic step.

As usual, you are spot on – this is a story universities need to care about. I have a question: How relevant are the differences in employment rates and salaries by program area? There’s no info in the report on further studies after graduation (that I can find). Results from the BC Baccalaureate Outcome Survey suggests this is an important part of the picture. For example, from the 2014 Survey of 2012 graduates (http://outcomes.bcstats.gov.bc.ca):

9% of the surveyed Business, Admin and Management (the largest program in the Business category) graduates were enrolled in full time studies at the time of the survey.

26% of the surveyed Psych, General (the largest program in the Social Science category) graduates were enrolled in full-time studies at the time of the survey.

If the situation is similar in Ontario, then I think prospective students who use the reported differences (from the COU Grad Survey) in employment rates and salaries to compare outcomes of Business and Psychology graduates (i.e. using Social Science as a proxy for Psychology) would be missing something important. This generalizes to other comparisons between Applied/Professional and “Academic” first degrees (Bio, Natural Sciences, Math, etc.).

What do you think?

They do ask that question in the Ontario survey (and employment rates are expressed as a percentage of those who are *not* in FT studies) – I have never seen the results, though.

This strikes me as an excellent opportunity to decouple university education from job-training, liberating the university to pursue higher studies. If universities aren’t working to produce highly-paid (and, therefore, taxable) graduates, maybe government and society in general should question their reflexive belief that that’s what a university education is for.

My guess is this would be accompanied by them questioning why on earth they are paying over 1% of GDP for something which is has nothing to do with the labour market.

We’d need to explain that there’s more to society than a labour market. We’re educators and should be willing to.

Besides, maybe we could just hive off some of the more expensive professional schools, and fund them separately. Teaching and doing research in the humanities or even the pure sciences isn’t, in principle, very expensive.

By the way, you may be interested in this recent New Yorker article, or at least its sources: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/09/07/college-calculus

You’ve probably seen it already, but it would be wrong of me to neglect pointing you to it, especially as it ends on more or less the same point that I made, above.