[the_ad id=”12755″]

One of the unique aspects of Canada’s higher education funding system is its regime of Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) and various kinds of public subsidies to these plans – the Canada Education Savings Grant (CESG), the Alternative Canada Education Savings Grants (A-CESG) and the Canada Learning Bond. What are all these things, and do they work as intended?

Let’s start with RESPs, which are simply accounts in which interest and capital gains are allowed to accumulate tax-free. As far as I can tell, these are a Canadian invention, and they date back to the big tax law changes of 1971-2. Americans have their version of these as well (they are called “pre-paid tuition plans” or “529 plans” after the section of the tax-code which created them), but they date only from the mid-80s. These were of fairly minor interest for a long time, because they were not very flexible, and it was possible to lose money on them (if your child never attended post-secondary education, for instance).

But then in the late 1990s, the federal government made two changes to these programs. The first change was fairly minor – allowing parents to transfer RESP gains to an RRSP if the intended beneficiary did not attend post-secondary education. The bigger one was the creation of the Canada Education Savings Grants: a 20% matching grant (up to a maximum of $400 per year).

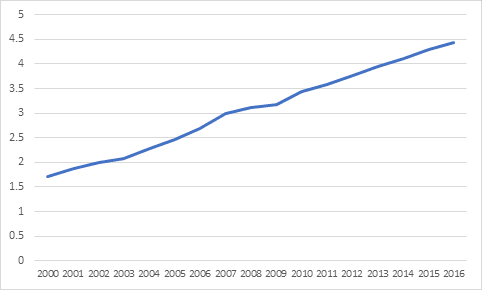

Its hard to overstate how big a deal this was in education finance. Here’s a graph showing annual contributions to Registered Education Savings Plans (data is from the CESG annual statistical review and dollars are unadjusted, which makes it look a little bit more spectacular than it actually is). The first billion or two in annual contributions was probably just parents shifting over savings from other types of instruments to these new accounts. But the fact that annual growth is consistently in the 5% range implies it has been the catalyst of an ongoing revolution in the way Canadians pay for post-secondary education. As of 2016, 51% of all Canadian children aged 17 and under had RESPs in their name.

Figure 1: Annual RESP Contributions, in Billions of Dollars

Of course, this approach was immediately criticized (by me among others) as being unduly generous to upper-income Canadians, who had far more ability to take advantage of this subsidy than others. After a few years, the Government of Canada responded by creating Canada Learning Bonds, and the “A-CESG”, which is a 40% match for families in the bottom income quartile (more or less – the income thresholds kind of match up) and a 30% match for “middle-income” families (basically 2x the line for the 40% match, which lines up with around the 60th percentile of family income). It has taken awhile, but this has had an effect. Back in 2006, just 16% of total program expenditures went to low and middle-income families (i.e.. those eligible for A-CESG); in the past decade this figure has risen to 43%.

There doesn’t seem to be much doubt that CESGs incentivize PSE savings (for more on this, see the summative evaluation of the program here). But the bigger question (which for some reason the summative evaluation does not address) is: does any of this affect access to PSE or decision-making about choices about PSE? Some great new data came out last week on the question of savings (though not specifically CESGs from the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC). Do read the whole report, but the key takeaway is that while there is no evidence of a direct relationship between “early-stage savings” (i.e. savings before age 14/15) and post-secondary aspirations, there is some evidence that savings allows some students at the financial margin to choose universities over colleges.

You can, if you want, build a case for CESGs from this. We know CESGs increase savings, and increasingly so among lower-income groups. We know savings increase choice in – if not access to – post-secondary education. So, we can probably say that these are an effective tool to increase affordability in PSE, which in turn leads to increased choice. Whether they are a particularly cost-effective way to achieve these goals is another question entirely.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post