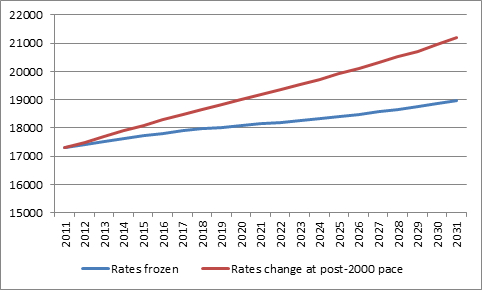

Yesterday, we saw that if one replaces a steady-state assumption about the work-habits of older workers, with a graph that extends recent trends in employment for that age demographic into the near future, then total employment projections rise by 2.1 million over 20 years, more or less wiping out the whole “future labour shortage” theory.

Future Employment Rates, Based on Different Assumptions About Employment Rates Among Workers Over 55

So what are the implications of this?

The first is to avoid complacency. There’s no guarantee that the number of employed older workers will in fact continue to grow. Thus, it’s important to keep removing barriers to continued participation in the labour force, making it as easy as possible for this figure to rise.

The second implication is that the argument for raising immigration quotas might not be as strong as it’s sometimes made out to be. If there is no labour shortage, there is less need to import labour. This is not to say we should decrease immigration (the projections in that chart assume steady-state policy of 250,000 immigrants per year) – and there are certainly arguments for increasing immigration that are not strictly related to meeting labour shortages (increasing the pool of entrepreneurial potential, for instance). But the idea that we’re going to need ever larger numbers of guest-workers to deal with labour shortages is probably overblown.

The third is that, paradoxically, if more older workers stay on, the average skill level in the economy (as measured by credentials) will fall, as older workers tend to have fewer credentials than younger cohorts. The effect of this shouldn’t be exaggerated; there’s more to skills than credentials, and older workers who stay on are disproportionately likely to have advanced education themselves. But it does suggest several very important policy directions, as far as education is concerned.

For starters, Canadian policymakers will need to develop better continuing education programs, in order to help older workers keep their skills sharp, and their credentials up-to-date. As any number of OECD reports will tell you, education and training among adults is not a Canadian forte; changing this is therefore a real and urgent priority.

Another policy issue worth bearing in mind is that, whatever the future labour market situation turns out to be, the best insurance against a future skills shortage is to ensure that our shrinking pool of young people get the best possible educational foundation from which to start their careers. This means raising standards in primary and secondary education; it means wider access to a post-secondary education system which produces curious, innovative, and energetic graduates; and it especially means an extra effort to raise educational attainment among historically under-represented groups, such as our First Nations.

Rising educational standards, broadened access, and better adult education. That’s the trifecta we need to focus on.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post