Last week, I wrote a piece about how the professoriate is aging and how these aging professors are taking up an increasing fraction of university budgets. My back of the envelope calculation suggested that for the extra $1.15 billion we are spending on this group compared to 15 years ago, we might be able to hire as many as 10,000 new, younger profs and thus help renew the professoriate.

(To be clear this would not mean 10,000 extra professors, it would mean a little over 5,000 as of course we’d have to lose some professors to free up the money. Still, 5,000 professors would increase total faculty complement across the country by 11% or so, which is not nothing).

Anyway, this finding provoked much debate on the twitters and elsewhere, and many good points were made both pro and con sides of the issue. But marring all those good points was one seriously bad point, one which I hear all the time and needs to be stamped out because it’s killing universities: “even if universities had that $1.15 billion, they wouldn’t hire new FT profs anyway”.

Assuming the average life of a professor is about 33 years, universities should see about 3% of their staff retire in any given year (the churn rate is higher, because people also leave for all kinds of retirement-related reasons, but leave that aside for now). However, as we noted last week, people seem not to be retiring at the rate they used to. So let’s say the retirement rate is actually just 2% per year. So over a given – say – six year span, if universities were not hiring full-time profs to replace retiring professors, we would expect the number of tenured or tenured-track profs to have fallen by about 12%.

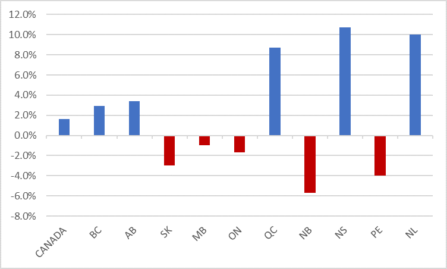

But that’s not even vaguely what’s happening at Canadian universities. Figure 1 uses data from Statistics Canada’s UCASS survey from pre- and post- its multi-year hiatus to show the number of full-time tenured and tenure-track profs. Across the country as a whole, the number of professors actually rose slightly. And while the number fell slightly in a number of individual provinces (e.g. Ontario), it fell by nothing like the 12% one would expect if in fact universities were not replacing their retirees. Only in New Brunswick does that narrative seem even slightly true, which one would expect since (as I noted back here) the province’s higher education system has been in full-on disaster mode for several years now.

Figure 1: Change in number of Full-time Academic Staff by Province, 2010-11 vs. 2016-17, Canada and Provinces

Source: CANSIM 477-0017

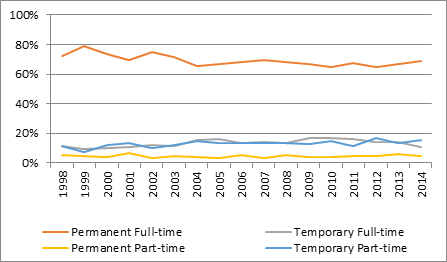

Well, yeah, some might say, but what about sessionals and part-timers? Those are through the roof, right? Nope. The Canadian Association of University Teachers, in its ever-handy Almanac, regularly publishes a very interesting data cut from the Labour Force Survey. And what it shows is that of the people who say their primary job is teaching at a university, roughly 70% say they are permanent full-time employees and only about 25% say they are on temporary contracts – and those numbers have barely moved in fifteen years.

Figure 2: Academic Staff at Universities by Employment Status and Permanency, Canada, 1998-2014

Source: CAUT Almanac

(OK, yes, the LFS is a somewhat tricky instrument to use for looking at higher education staff, because with a random sample of just 55,000, on average it probably only includes about 150 people who teach in universities, so take the above numbers with a grain of salt. That said, the results seem to be relatively consistent over time, which suggests some degree of reliability).

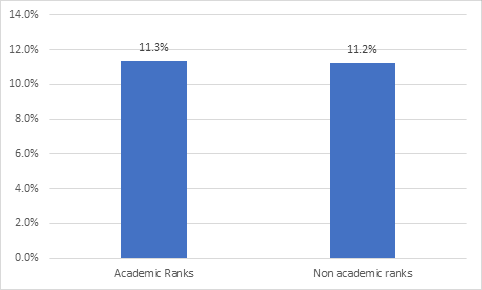

Some might still try to argue about all those other sessionals, the ones who have outside jobs but are coming in and teaching a course or maybe two per year. Their numbers have skyrocketed, right? Well, first, it’s not entirely clear why we’d worry much about this group (they have other sources of income, they’re probably teaching because they enjoy it and students are getting exposure to people with current professional experience). But more to the point, there’s no evidence these numbers are going up either. We don’t have direct numbers on employment, but thanks to the Financial Information of Universities and Colleges Survey, we do know how much universities are spending from their operating budget on salaries for people in the academic ranks versus what they are spending on salaries for “other instruction and research” (which mainly means sessionals, because people on the research side tend to get paid out of the research budget). If we were seeing a big jump in the use of said type of sessionals, we’d see a big increase in this kind of spending. Here’s the increases for 2015-2016 vs five years earlier:

Figure 3: Real Increase in Aggregate Salary Expenditure, Academic Ranks vs. non-Academic ranks 2015-16 vs. 2010-2011

In short: no evidence of disproportionate increase in use of sessionals, and prof numbers are constant or rising in face of a 10% or so loss in numbers due to retirement.

So why do people believe the opposite?

The answer here is discouraging, but it’s a variant on the point I made back here about disciplinary selfishness. By and large, faculty do not care (or, at least, are blissfully unaware) if the university replaces a permanent academic with another permanent academic. Rather, what matters is whether a whether a department gets to replace them. In this way, the university exercising its basic management function – reallocating staff in response to changing priorities and student enrolments – is transformed into an act of unthinkable bean-counting neo-liberal austerity.

But an honest reading of the data shows that’s just not true. That argument is done, dusted, buried. Let us hear of it no more.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Instead of arguing against a nameless ‘some’ or ‘some might say’ you need to find a real person who actually says it and respond to *their* arguments and data.

So here’s the thing: I often hear opinions when people email me or tweet me or speak to me at conferences or speeches or whatever, and if I hear it often enough, I respond to it. I don’t think any of these people would appreciate it if I cited them because my platform is a whole lot bigger than theirs. I don’t think it would be fair.

That doesn’t mean the opinions don’t exist.

Maybe they’re looking at Ontario’s colleges. According to the Colleges Ontario 2013 environmental scan, from 1995/96 until 2011/12, the number of full-time college administrative staff increased by 55 per cent. During the same time period, the number of full-time academic staff increased by less than 10 per cent. At Humber College, from Sept 2005 to Sept 2009 the number of students increased by 25% while full-time faculty numbers increased only 12%. In 2005, 42% of faculty at Humber were full time, but by 2015 that had fallen to 24%.

Hi HESA Towers. Re this statement in today’s column . . .

. . .”first, it’s not entirely clear why we’d worry much about this group (they have other sources of income, they’re probably teaching because they enjoy it and students are getting exposure to people with current professional experience)” . . .

For many faculty associations and faculty unions, this is not the reality they face when coming to the bargaining table. And for those of us “on the other side of the table”, we find ourselves bargaining in an environment where the argument is that we are essentially being abusive of those who teach sessionally not because they have a good job at Price Waterhouse and just enjoy teaching young people in an accounting class one night a week after work but because they teach 10 or 12 courses a year to try make a full time living. (And that was never the intent of sessionally hired faculty.) If all we had to manage were tenured faculty teaching full time numbers of courses and then people who teach one or two courses a year on contract, the situation re what the FAs call the precariously employed would disappear. But we have this other group, sometimes substantial in the scheme of things, that regard their cobbled-together sessional work as an underpaid full time occupation. All by way of saying that contract or sessional faculty are not a homogenous group and if we don’t parse out that difference, we probably have the wrong conversation about whether we have a problem or not with the balance between full time permanent and part time impermanent faculty in the PSE system.

As always, I appreciate the careful attention to data detail in the articles. jc

(It might be interesting, by the way, to compare these numbers with US numbers. Our sense of the situation is often informed by the American press.)

Whether it is becoming more common or not, the practice of hiring sessionals (like, less controversially, the hiring of research-only faculty) breaks down one of the central principles of a university, the unification of research and teaching. It is therefore not merely a concern for any one department — though it may often play out between departments — but an existential threat to the university as such. I wonder whether the numbers are holding up as universities create more positions which are permanent and full-time, but not true tenure-stream positions. This would seem a lesser evil than keeping a large fraction of the faculty in the precariat, but still corrosive to the idea of a university.

It seems at least as much of a threat as the tendency of universities to transform into polytechs by, as you say, “reallocating staff in response to changing priorities and student enrolments.”