Note: A version of this post appeared in the Telegraph-Journal (paywall applies)

To Fredericton, where the new Conservative Government had its Throne Speech on Tuesday. The key line for post-secondary education (which, for the most part, was ignored) was this one: Your government will undertake an evidence-based review of existing programs supporting post-secondary education and compare and contrast their effectiveness with the canceled broad-based tax credits. (nb. the tax credits were cut to create a Targeted Free Tuition program, described here among other places)

You know what? We at HESA Towers can help with that! Evidence-based analysis is what we do! Let’s see if we can’t save the cash-strapped government of New Brunswick a few bucks and do some of this analysis for them, gratis.

First of all, though, we need to be careful about our terms. The “broad-based tax credits” that the government talks about came in two varieties. The first was a graduate tax rebate (technically the New Brunswick Tuition Tax Cash Back Credit), which was passed in 2006 under the Lord Government. This rebate allowed PSE graduates from any province to get up to $10,000 off their New Brunswick taxes over a number of years and it was – unusually for Canada – refundable. The second was the provincial version of the old federal suite of non-refundable tax credits for tuition and an “education amount” of $200/month (“old suite” because the feds eliminated the education amount in 2016, though the tax credit for tuition still exists).

The purpose of these two sets of credits were somewhat different, but in neither case was it “supporting post-secondary”, if by that we mean direct support to the institutions providing post-secondary education. In the case of the non-refundable credits, their purpose generally was to provide students and/or their families – the credits were transferable – with tax-based financial support to offset tuition and living costs (I suppose if you squint hard enough that’s support to institutions because it makes it easier for students to pay tuition, but it’s a stretch). In the case of the graduate tax rebate, students received no money unless and until they graduated, so it is extremely difficult to make the case that it had anything to do with access (not that the spinmeisters didn’t try, of course). Rather, the purpose of that money was to “encourage skilled, well-educated workers to choose to live and work…in New Brunswick”. Nothing wrong with that goal, of course, but worth pointing out that it’s quite different from “supporting post-secondary students,” let alone “supporting post-secondary institutions”.

A worthwhile question at this point is “did the tax credit increase the number of post-secondary graduates in the province?” One way to find out is to ask the people who used the credit whether the credit made a difference in their decision to live there, which fortunately the Finance Department did to everyone who submitted a request for the tax credit. I will leave it to the Government to release the exact results as part of their evidence-based review, but as I understand it, the answer is “not much”: of the various factors graduates were asked about, the tax credit was least often credited as having had an effect on location.

Another way to answer the question is to ask all students: “how much money would it take to convince you to move to another province?”, A few years ago, we at HESA asked a few thousand students across the country a) in which province they thought they would end up working, b) how much money they thought they would make and c) how much they would have to be paid to agree to do the exact same job in each of the other provinces. Basically, it was a way to estimate reserve wages for working in each of the provinces. You can see the full results here; what we found with reference to New Brunswick was that 18% of respondents would be happy to work there for the same amount of money or less than they would elsewhere, whereas 50% said they’d either require a pay boost of $25,000 or “would never move there”. Only 2% said that a sum in the range of what the graduate tax credits provided would be enough to change their minds. Draw your own conclusions about the efficacy of said tax credits.

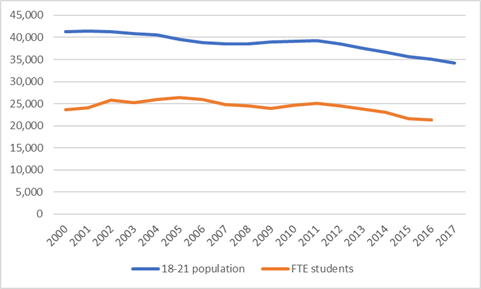

Now, one idea that seemed to pop up a couple of times during the election campaign was that the elimination of the tax credits and their replacement by a targeted free tuition regime had had some kind of negative effect on enrolment. And it is certainly true that domestic enrolment numbers are falling in New Brunswick. But there is a pretty straightforward reason why this is happening: as figure 1 shows, FTE student numbers have been moving in lock-step with the numbers of 18-21 year-olds resident in the province since about 2005. Unless you’re prepared to argue that changes to tax credits and student aid programs in 2016 had a negative causal effect on the birth rate in the late 1990s, this isn’t a very promising line of inquiry.

Figure 1: New Brunswick Youth (18-21) Population and Domestic FTE Enrolments, 2000-2016

I could go on at length here, but I won’t. The point here is not that there is no reason for a new government to wonder whether the previous government’s initiatives were sensible. It’s always good to try to find more effective ways to spend public money. And we at HESA Towers always applaud governments who want to conduct evidence-based reviews. The point, rather, is that based on the evidence which is currently available, it’s really hard to see much of a case for the previous tax regimes having done much good, or that their elimination did a lot of harm.

And, to reiterate our offer about saving a cash-strapped provincial government some money: if the government just puts some data out there. we’re happy to contribute some work in gratis to make sure this evaluation gets done right. Just call us.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post