Morning, all. It’s time for our annual provincial budget round-up. University Affairs has done its round-up of budget announcements; I’m here to put the whole set of financial commitments under the lens and give it some long-term context.

A couple of caveats before I start.

First, PEI is not included, for the simple reason that the government chose not to submit a budget before going to the polls a couple of weeks ago. But, in the big fiscal picture of Confederation, PEI’s budget is minimal (last year its PSE spending was 0.4% of the national total), I think we can get away with this.

Second, the Ontario budget is a bit of a guess. Under the Liberal government, the presentation of the Ontario budget became next to useless as a guide to what was being spent each year, but the Tories really have taken it to new heights by not setting out actual new program costing anywhere in the document. Add to the fact that Ontario, unlike every other province in the country, does not publish estimates at the time of the budget (it usually waits about six months) and that the budget line-item for PSE includes college balance sheets (meaning that an increase in college income from international students shows up as increased spending on provincial books) and you could not possibly engineer a process designed to tell you less about actual provincial spending than the Ontario budget. Every single person responsible for budget design in the offices of the Premier and the Finance Minister should be ashamed about the lack of transparency. This is no way to run a democracy.

So, I’ve taken last year’s figures and adjusted slightly for what I believe to be the costs of additional targeted funding for projects targeted towards training additional health care workers and that’s about all I can do.

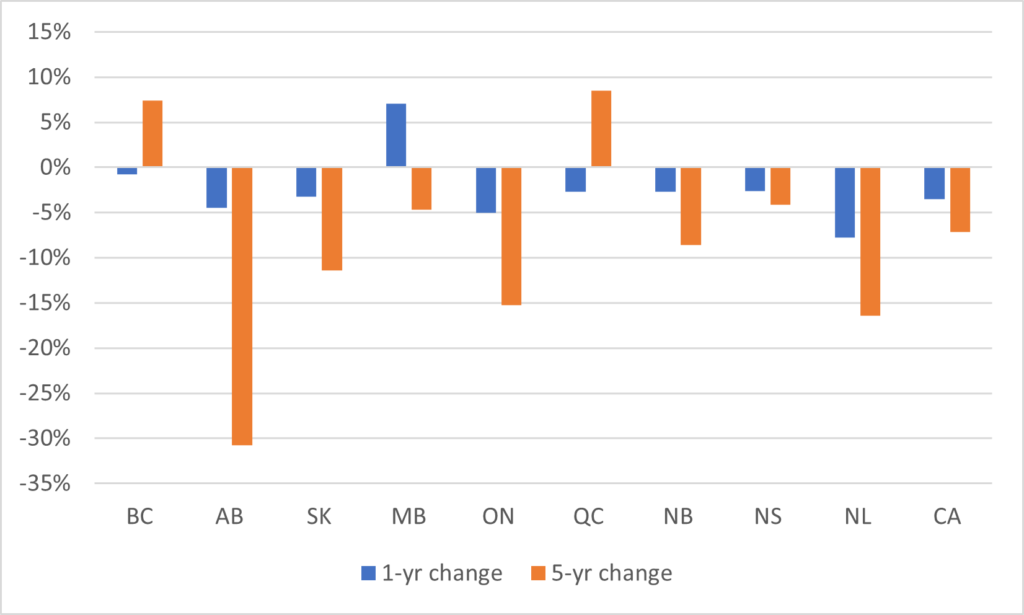

With all that in mind, Figure 1 shows the 1-year and 5-year changes in real provincial support to post-secondary education based on provincial budgetary allocations. As you can see, inflation is really doing its work. In this round of budgets all provinces except Newfoundland and Labrador increased funding in nominal terms; however, in real terms only Manitoba saw an increase. And what an increase! 11% year-on-year, the largest anywhere in Canada since Newfoundland in 2010, at the height of that government’s era of getting-drunk-on-oil-revenues. But over the past five years, only British Columbia and Quebec have increased funding.

As for the laggards: well…the figure for Newfoundland and Labrador is a bit misleading in that five years ago there was quite a large capital project that skewed the baseline numbers upwards: if we were to look at operating budgets alone the drop would be about 16% which is still big but not that big. The Alberta drop of 31% after inflation is pretty horrifying but is actually not quite as bad as what the UCP said it was going to do in its first budget. And the Ontario government’s nominal freeze on grants is now equal to a 15% reduction in real funding, with no end in sight.

Figure 1: One- and Five-Year Changes in Real Budgeted Provincial Transfers to Post-Secondary Institutions, by Province, 2023-24 Budget Cycle

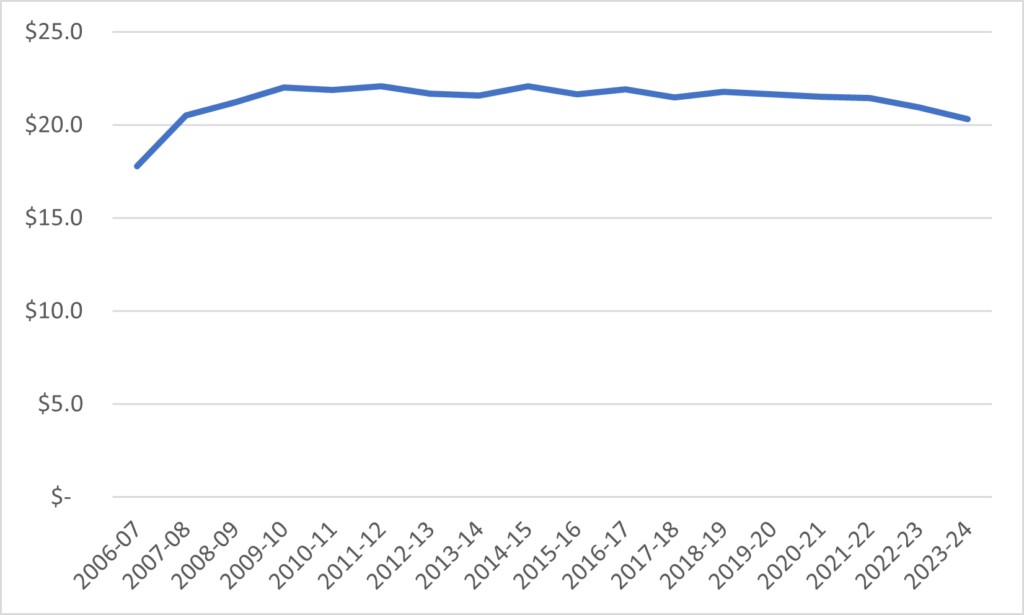

And what does it look like if we aggregate all that provincial data and stick it in one long line-graph? Glad you asked. As Figure 2 shows, total provincial transfers to post-secondary institutions were pretty flat from 2010 to 2020. That is not to say they were flat in every province – just that the ups and downs across the country offset one another. Since then, however, a combination of nominal freezes in Ontario, bug cuts in Alberta and the effects of much-higher-than-usual inflation have combined to create a real decline of about 7% since 2018-19.

Figure 2: Aggregate Budgeted Provincial Transfers to Post-Secondary Institutions, in Billions of $2023, Canada, 2006-07 to 2023-24

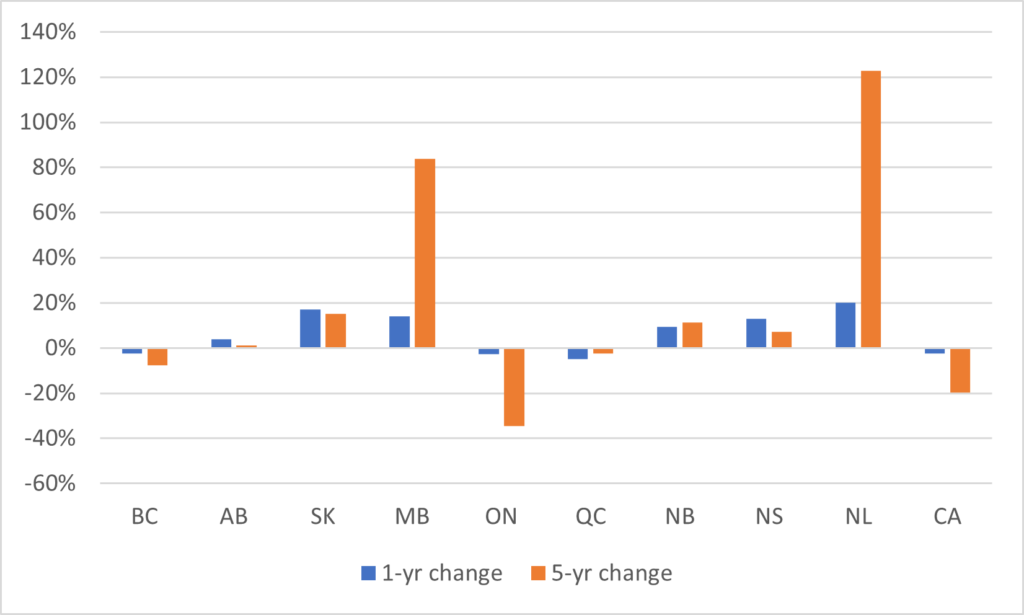

Now, over to student financial aid. This one is a bit harder to track because some provinces have weird ways of accounting for – or at least publishing – their data on student aid. For instance, I am pretty sure the jump in Newfoundland and Labrador is a change in how their data is provided rather than anything else (although 2018-19 was the year the province changed the way it administered funding and marked a big drop from previous years). As Figure 3 shows, provinces are roughly evenly split, both over a period of one year and five years, in terms of increasing or decreasing their student aid budgets. However, because Ontario made such drastic cuts to its system in 2019, the national aggregate of provincial student assistance is still down roughly 20% over the past half-decade.

Figure 3: One- and Five-Year Changes in Real Budgeted Provincial Expenditures on Student Financial Aid, by Province. 2023-24 Budget Cycle

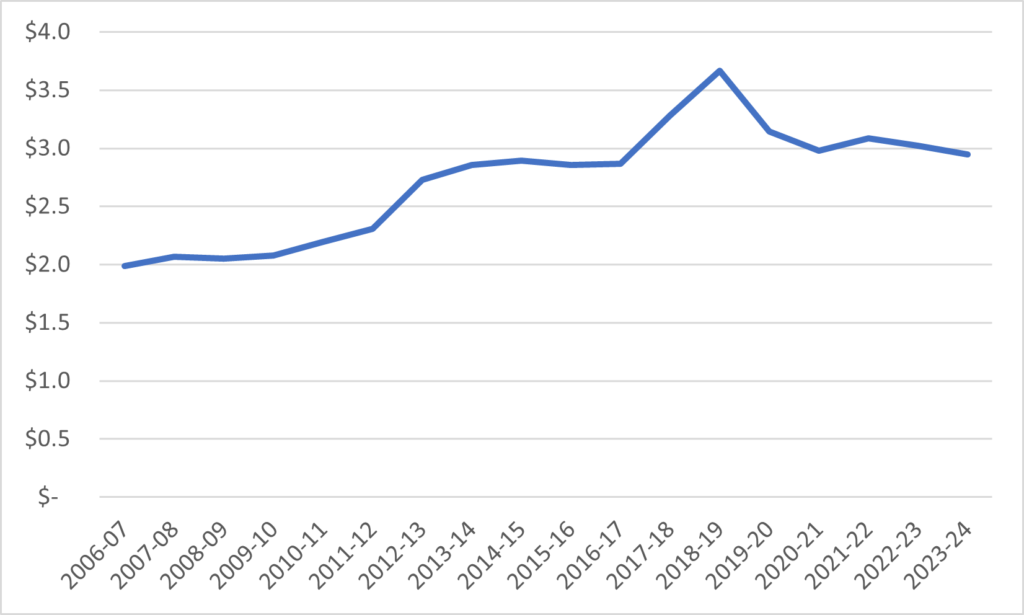

And that brings us to Figure 4, which looks at aggregate budgeted student assistance funds over time. This graph looks quite different from Figure 2. Despite cutbacks, real provincial student aid budgets are up by a third over where they were in the late 2000s. They are also down about twenty percent from where they were when Ontario still had its targeted-free-tuition program under the Wynne government.

Figure 4: Aggregate Budgeted Provincial Expenditures on Student Financial Assistance, in Billions of $2023, Canada, 2006-07 to 2023-24

And that’s your budget analysis for 2023. Tl;dr: there is absolutely no indication that any province – save possibly Manitoba – seems interested in reversing the long-term trend of declining per-student and per-unit of GDP spending on higher education. Oh, and provinces like giving money to students more than they like giving money to institutions.

A short programming note: tomorrow is podcast day and I’ll be talking to Ellen Hazelkorn about recent developments in higher education in Ireland. Next week the blog will be off while I am working (and doing a bit of sightseeing) in sunny Uzbekistan. Regular blog service will resume May 1.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Isn’t the real issue “what are we getting in return for all that public spending?” If you have posted on what has happened to research output and impact, degrees granted, quality of graduates… then it would be great to see if spending is correlated with the promised societal impacts of said spending. If we cannot demonstrate impact and universities are seeking public funds based on the public having faith that money spent has a longer term payoff then we need to recognize that. If there is a measurable impact then someone could attempt a return on investment type of calculation. But I am not sure what we gain from focusing on spending in isolation since it gives no guide as to how much we need to spend on universities. If universities are suffering from Baumol’s Cost disease, cost increase with no productivity increase, then what’s the cure?

Preemptive apologies: This may be a little too cynical, but it’s no fun if you’re always distanced/objective/professional.

This blog ties in nicely with the blog “Historical Higher Education Data-Palooza Part 3” from April 17 that clearly demonstrated the ever increasing role of fundraising and student fees. There seems to be some silver lining from the student aid side. However, for some provinces this has only a very small impact and cannot compensate for the loss in operating budget. There also seems to be a race to the bottom that looks like a popularity contest among provincial politicians: “I am tougher on universities than you are.” The problem with this is that politicians take the services of their provincial universities for granted. However, philanthropic fundraising and tuition hikes can only go so far. Universities will therefore be tempted to put more focus on two kinds of programs:

– low-cost high-revenue (well, you know, some politicians like to chastise “useless” programs, but secretly, everyone loves a cash cow);

– programs that are easily explained to politicians and the public (the easier explained, the more money can be charged!).

…and cut high-cost low-revenue programs (but no cuts to varsity sports, for heavens sake, that’s a big political no-no!).

This disdain for universities is partly driven by a perception that universities graduate the wrong kind of people: “We need more welders/carpenters/mechanics.” It so happens that I do have friends that worked in the trades and then retrained for other jobs or went to university. Their stories are always similar. Pulled into trade colleges out of high school with the promise of lifelong rewarding careers, and then treated and paid like unskilled laborers after graduation, and eventually laid off when manufacturing took a downturn.

Notwithstanding, the statement “We need more trades people and less university graduates” is very popular in many circles, and yet no politician would ever dare to go to a high school graduation ceremony and tell graduates and their parents “You new graduates must all go into the trades. I do not want you to attend university!” – nor would they prevent their own children from attending university. I have seen my fair share of children of politicians (who subscribe to the tough-on-universities mindset) in my classes, even in the liberal arts. It’s all so great if you can talk about in general populist terms without ever telling high school graduates to their faces that they must not attend university. More often than not, the Right Honourable MLA XY wants everyone to become a trades person, except their own child.