I had the pleasure of spending a couple of days in Alberta last week, and I would spend some time writing about the ways in which Alberta higher education is structured differently from the rest of the country. For that, I have to get into the public finance weeds.

Twenty years ago, Alberta arguably had the best public service in the country (it’s still pretty good, but it’s fallen a bit). One of the innovations they hit on as they ran balanced budgets during the late 1990s was the concept of “ministry business plans”. In these, the government lays out three important things. First, it details the government’s priorities in each ministry; in the case of Advanced Education, it lays out what the government wants the system to achieve (which, alone, puts it a class ahead of pretty much every other province, where governments often behave as if what they want from the higher education is to shut up and not cause problems).

Second – and this is pretty dope – the ministry sets targets for the system to achieve in each of the priority areas and reports on those targets each year. Wild, right? That’s dangerously close to governments taking responsibility for outcomes, which is generally verboten in Canadian politics (doubly so when it comes to education). You can see why this was considered radical when it was introduced.

Third – and this is practically unheard of – the ministry budgets forward on a triennial basis. That is, the ministry roughly knows what its budget will be three years out. Sure, sudden changes in oil prices might send those numbers up or down, as can changes of government (though this was not a familiar concept in 1990s Alberta), but basically the Ministry and everyone associated with it can make long term plans. Which, you know, cool.

(Changes of governments are capable of causing whiplash. Take the 2018-21 business plan, written by the NDP. It prioritized i) accessible, affordable learning opportunities, ii) having a system contribute to Alberta’s economy, society, culture and environment – the accountability measure for which includes graduate satisfaction rates for some bizarre reason – and iii) an accountable and co-ordinated system. The 2019-2022 business plan, written by the United Conservative Party, prioritizes i) ensuring Albertans have skills to get jobs, ii) fiscal responsibility and iii) PSE institutions having the flexibility to innovate and compete. Those are perfectly legitimate sets of objectives but getting institutions to switch their focus from one to the other isn’t exactly easy).

There’s one problem here, though. For unclear reasons, the Government of Alberta decided that all of the provinces’ colleges’ and universities’ books had to be included on the provinces’ books. This isn’t entirely unknown elsewhere – it’s partially true in British Columbia, where the auditor-general ruled that institutional debt had to be carried on provincial books because the province would likely have to bail out wayward institutions that got into financial trouble (probably fair). In BC, the main consequence of this policy is that during recessions, the province puts the kibosh on institutions taking out mortgages to construct new buildings, because the debt shows up on provincial books.

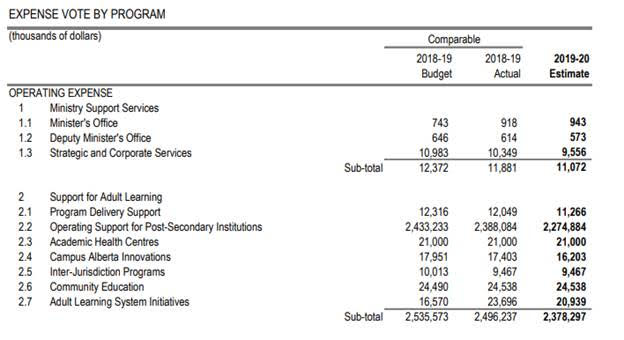

In Alberta, things are wackier. On budget nights, most colleges and universities look to the Government Estimates to gather figures like this:

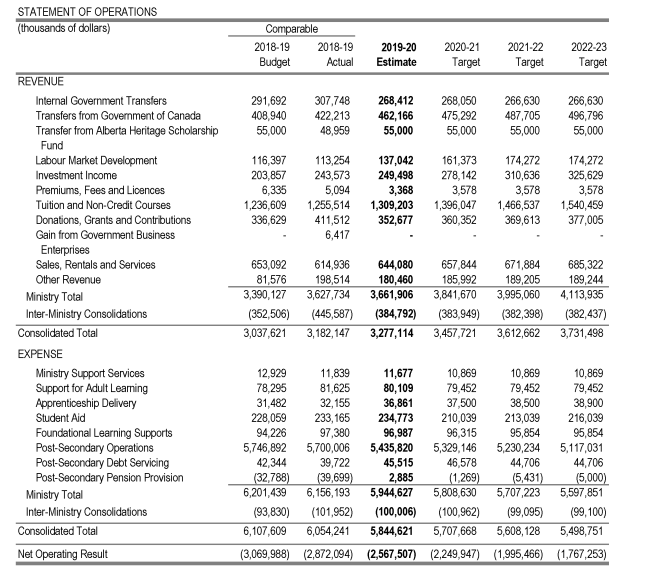

Simple enough, right? Just look at the line where they say how much they are going to put into institutions (2.2). But in Alberta, government relations-types also have to consider the Business Plan, which expresses things completely differently (my apologies to all of you reading this on phones):

Note here that there is a “consolidated total revenues”, “consolidated total expenses” and “net operating results”. “Revenue” is money from everyone except the Ministry of Advanced Education. Expenses is total expenses. And “Net Operating Results” (which is always a loss), is what the Ministry of Education actually intends to spend.

This tends to mess people up: I had a journalist claim that the government intended to cut education spending by $550M between 18-19 and 22-23, because that was the fall in projected consolidated expenses. No, no, no. The government wants institutions to cut spending by $400 million. It’s going to cut its own spending by twice that, $1.1B (the figure is calculated from the annual declines in the consolidated total), and let the institutions make up the other half through higher fees and other forms of cost-recovery.

This is bizarre. It’s one thing for a government to cut transfers to institutions, but who in their right mind tries to limit total income/expenditure (would the government like the universities to turn away donations, for instance)? Unless the government includes only the consolidated totals on the balance sheet, in which case, by some batshit weird accounting, an institution accepting a major donation would have a negative effect on total government-wide expenditures.

Another problem with provincial accounting policies is that they don’t understand how institutions can run surpluses and yet have no disposable cash. You may want to read this hilarious explainer the University of Alberta had to write to the Government of Alberta and explain how things like endowments and restricted funds work, since apparently no one in government really understands them. It’s funny not just because government doesn’t get endowments, it’s also funny because the government of Alberta is apparently making the same arguments CAUT makes about university accounting policies. I’m sure faculty associations across the country can take pride in that one.

Anyhow, the upshot here is this: every other government in the country writes a cheque to institutions, sets rules of varying stringency around opening new programs, recruitment, and tuition and says “vaya con Dios”. In Alberta, the control extends to actually controlling both institutions’ expenditures and revenues more directly.

And this is part of what’s making the government’s approach to institutional performance indicators so confused. More on that tomorrow.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

When you specify a difference like 1.1 B can you please reference the numbers you use to make this calculation?

For example, I’m assuming the journalist 550M comes from the row (consolidated total) 6,054,241 (2018-19 actual) – 5,498,741 (22-23 target).

Does the 1.1 B come from the row (net operating result) 2,872,094 (18-19 actual) – 1,767,253 (22-23 target) ?

I very much appreciate your article, and writing, but as much as I want to understand I found myself struggling.

thank you for any feedback can you provide,

Joseph Mann