There is a lot of talk these days about populists and universities. There are all kinds of thinkpieces about “universities and Trump”, “universities and Brexit”, etc. Just the other day, Sir Peter Scott delivered a lecture on “Populism and the Academy” at OISE, saying that over the past twelve months it has sometimes felt like universities were “on the wrong side of history”.

Speaking of history, one of the things that I find a bit odd about this whole discussion is how little the present discussion is informed by the last time this happened – namely, the populist wave of the 1890s in the United States. Though the populists never took power nationally, they did capture statehouses in many southern and western states, most of whom had relatively recently taken advantage of the Morrill Act to establish important state universities. And so we do have at least some historical record to work from – one that was very ably summarized by Scott Gelber in his book The University and the People.

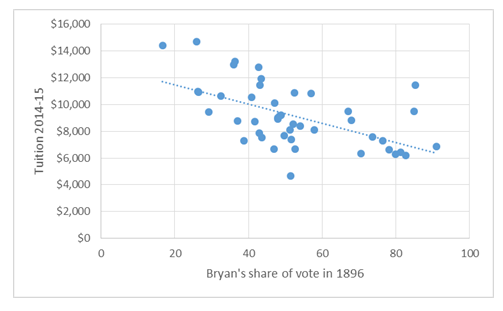

The turn-of-the-20th-century populists wanted three things from universities. First, they wanted them to be accessible to farmers’ children – by which they meant both laxer admissions standards and “cheap”. That didn’t necessarily mean they wanted to increase expenditures on university budgets substantially (though in practice universities did OK under populist governors and legislators); what it meant was they wanted tuition to remain low and if that entailed universities having to tighten their belts, so be it. And the legacy of the populists lives on today: average state tuition in the US still has a remarkable correlation to William Jennings Bryan’s share of the vote in the 1896 Presidential election.

Fig 1: 2014-15 In-State Tuition Versus William Jennings Bryan’s Vote Share in 1896

The second thing populists wanted was more “practical” education. They were not into learning for the sake of learning, they were into learning for the sake of material progress and making life easier for workers and farmers; in many ways, one could argue that their attitude about the purpose of higher education was pretty close to that of Deng/Jiang-era China. And to some extent they were pushing on an open door because the land-grant universities – particularly the A&Ms – were already supposed to have that mandate.

But there was a tension in the populists’ views on curriculum. They weren’t crazy about law and humanities programs at state universities (too much useless high culture that divided the masses from the classes), but they did grasp that an awful lot of people who were successful in politics had gone through law and humanities programs and – so to speak – learned the tricks of the trade there (recall that rhetoric was one of the seven Liberal arts which still played a role in 19th century curricula). And so, there was also concern that if public higher education were made too vocational, its beneficiaries would still be at a disadvantage politically. There were various solutions to this problem, not all of which were to the benefit of humanities subjects, but the key point was this: universities should remain places where leaders are made. If that meant reading some Marcus Aurelius, so be it: universities were a ladder into the ruling class, and the populists wanted to make sure their kids were on it.

And here, I think is where times have really changed. The new populists are, in a sense, more Gramscian than their predecessors. They get that universities are ladders to power for individuals, but they also understand that the cultural function of universities goes well beyond that. Universities are – perhaps even more so than the entertainment industry – arbiters of acceptable political discourse. They are where the hegemonic culture is made. And however much they may want their own kids to get a good education, today’s populists really want to smash those sources of cultural hegemony.

This is, obviously, not good for universities. We can – as Peter Scott suggested – spend more time trying to make universities “relevant” to the communities that surround them. Nothing wrong with that. We can keep plugging away at access: that’s a given no matter who is in power. But on the core issue of the culture of universities, there is no compromise. Truth and open debate matter. A commitment to the scientific method and free inquiry matter. Sure, universities can exist without these things: see China, or Saudi Arabia. But not here. That’s what makes our universities different and, frankly, better.

No compromise, no pasarán.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Universities can exist without free inquiry, but only in the nominal sense: they’re called universities, but they don’t pursue knowledge as an end in itself, so they aren’t.

I know what you mean, here. Such a definition would, however, rule out pretty much rule out every university in the world prior to about 1812, and arguably a majority of them since then.

Maybe it’s best to call it an ongoing challenge: the humanists kept complaining that nobody appreciated their work, and the Oxbridge colleges were attacked in the eighteenth century for lacking practical relevance.