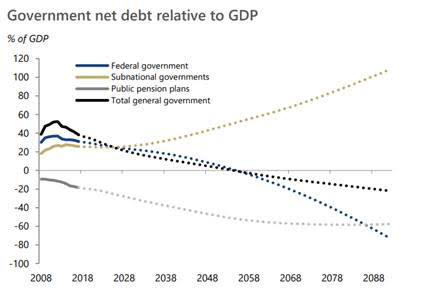

As I noted back on Monday, one of the basic dynamics we see in Canadian public finance is the long-term deterioration of provincial finances and the long-term improvement of federal ones, mainly due to changing demographics and the cost of heath care. Take a look at the projections from the Parliamentary Budget Office from their 2018 Fiscal Sustainability Report, which shows this trend rather clearly: long-term provincial government debt numbers are off the charts, while the feds are on a continuous path to zero net debt.

Now, although the real crunch in provincial government finances doesn’t happen for another couple of decades, provincial finance ministries are highly aware of the overall trajectories and are already looking for ways to change them. Which is why I am fairly sure over the course of the next few years we are going to see a re-emergence of the “fiscal imbalance” discourse of about 15 years ago. This may seem difficult to imagine at the moment, since last fall’s election was the first in 40 years in which no party made any promises about increasing transfer payments for health or social programs (equalization, a much smaller program, is a different story). But the history of fiscal federalism in Canada has taken some odd turns over the years and the 2020s aren’t likely to be different.

There are two ways to deal with fiscal imbalances. The first is to transfer money (or tax room) from the richer level of government to the poorer; the other is to transfer responsibilities from the poorer to the richer. Normally in Canada, the provinces have preferred to do the former rather than the latter, but as the fiscal balance tilts further and further towards the federal government it’s easier to imagine both scenarios.

And in post-secondary it’s easy to spot the one area where something like this could happen: namely, institutional infrastructure.

In the mid-2000s, provinces were accounting for between 70-95% of all infrastructure transfers to universities in the country. In this decade, two things have changed. First, thanks to the Government of Canada’s inclination to disguise counter-cyclical subsidies to the construction industry by funnelling it through the Harper government’s Knowledge Infrastructure Program (KIP) and the Trudeau government’s barely distinguishable Strategic Infrastructure Fund (SIF), federal expenditures on university infrastructure are now averaging close to $500 million a year, if you include CFI funds. College numbers would increase that figure even more.

Second, provincial infrastructure spending has declined substantially. A lot of that has to do with the fact that we no longer have the Stelmach government in Alberta spending nearly a billion dollars a year (because the oil boom is never going to end, right?), but particularly in the last 24 months, we have seen budgets in Alberta and Ontario, which normally make up over 50% of total capital spending, take an axe to this line item, such that – although hard figures for 2018 and 2019 aren’t really available – it’s a good bet that we are now seeing the lowest aggregate levels provincial spending in this area since the late 1990s.

So, if the feds have some money, why not get them into this field on a more permanent basis? Why not make the SIF permanent? The feds have history in this area. In 1960, the Diefenbaker government passed the Technical and Vocational Training Assistance Act, which provided money to provincial governments for construction of vocationally-oriented high schools and what would eventually be called community colleges. And KIP and SIF whistled into existence with nary a peep from provincial governments (IIRC Quebec has a special arrangement where it gets to pre-approve all projects submitted by institutions, thus satisfying the requirement that provincial supremacy in education remains intact).

Making SIF permanent would be a useful way to soak up federal dollars that might otherwise be used on any number of nonsense boutique research ideas. But it would also genuinely make capital planning in Canada a lot more rational. Provinces currently go through boom-bust cycles of capital expenditure – a permanent federal partnership might smooth that out a bit. Also, instead of having some sort of wild orgy of capital project proposals with 60-day deadlines whenever the feds decide there’s a recession and want projects that are “shovel-ready” (which is of course nonsense, since no project submitted on a 60-day deadline is shovel-ready), a permanent process would allow institutions to submit priorities slowly over a number of years, and for the feds to maintain a permanent roster of potential projects which could be activated. It might even provide a spur for improved campus master-planning at small and medium-sized institutions.

Just a thought, anyway.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post