Here are three interesting nuggets from last week’s Ontario University Application Centre’s data release.

Long Term Trends

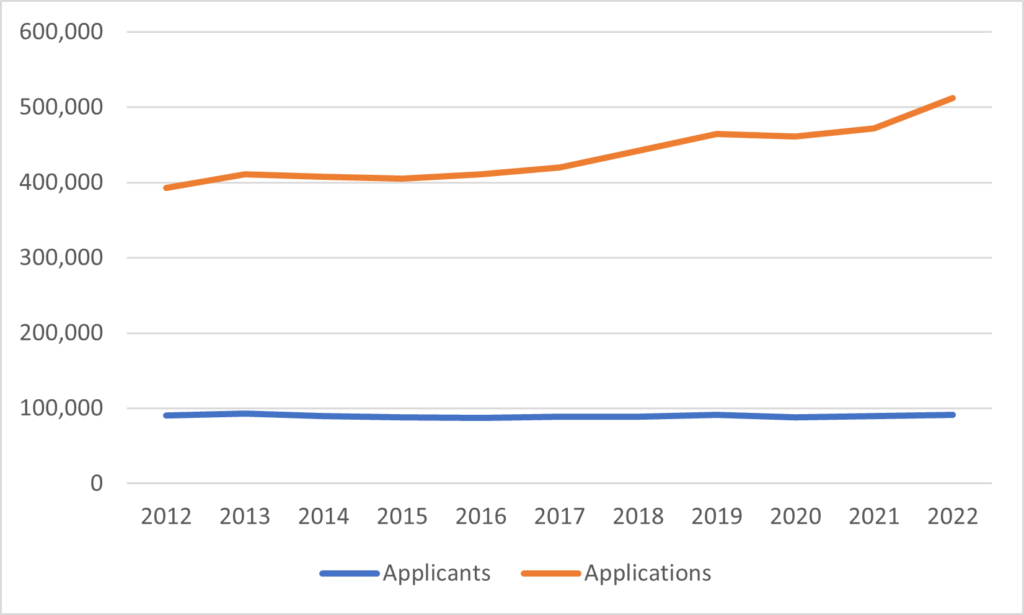

Students, on average, are applying to a lot more institutions than they used to. To wit, since 2016, the average number of applications per applicant was 4.7. It’s now 5.6.

Figure 1: Direct-From-High-School Applications and Applicants, Ontario, 2012-2021

This doesn’t just mean an extra $5 million to OUAC in fees: it affects the way we have to analyse data from institutions. You probably saw a lot of triumphant communications about “record number of applications”. Indeed, I’m pretty sure a majority of Ontario institutions hit an all time high in terms of applications: Ontario Tech was up a whopping 33%, Guelph saw a jump of 22%, Trent 17%, OCAD U 16%, Waterloo 15%, etc. But it’s not an increase in applicants, necessarily; it might just be the same number of students applying to more programs at the same university.

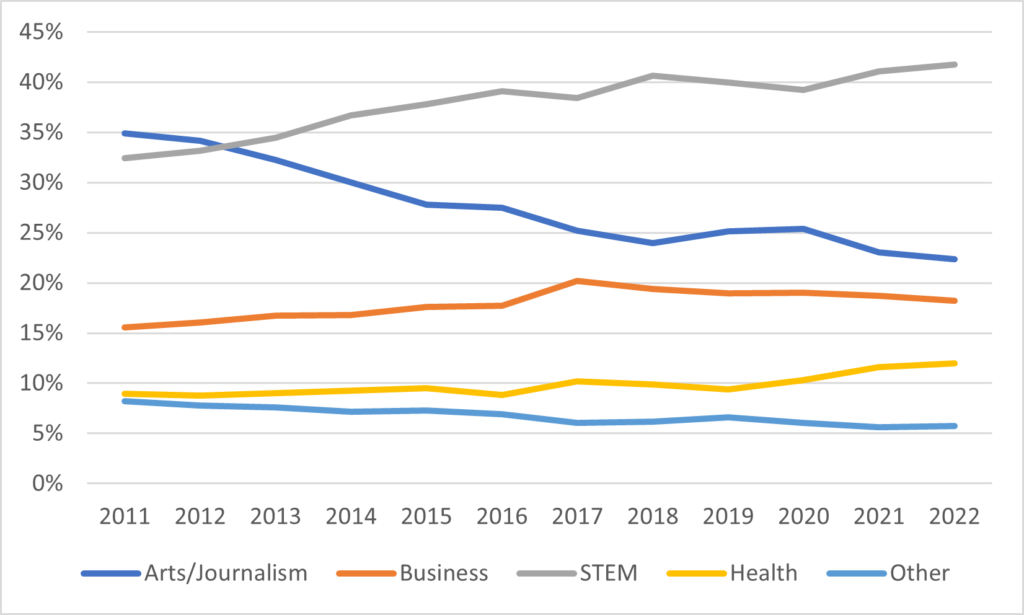

Unfortunately, we can’t whether this is the case because OUAC has stopped publishing data by applicants and now reports everything by applications. This was done in the name of simplifying data releases, which I kind of get, and they are being very nice about facilitating data access beyond what’s published, but there is a bit of a loss of data granularity. Basically, it means that whenever you try to look at trends over time, you have to take account of the fact that it is not just the number of applicants that are changing, but applicants’ behaviours with respect to applications as well. For instance, usually I monitor the number of first-choice applications by field of study, because it’s a purer measure of actual applicant preference. Now, I can only look at shares of total applications, as I do below in Figure 2. The overall picture isn’t too different from looking at it from a first-choice stand-point (see last year’s blog on this subject), but it does seem as though a few in-demand subjects – notably computer science – tend to look better on this shares measure than on the applicants measure, presumably because the field is in such demand that people feel it worth their while to file for five, six and sometimes seven program choices in order to get in somewhere. So, think of Figure 2 as being consistent with the overall picture of demand, but possibly exaggerating the interest in STEM fields.

Figure 2: Shares of Applications by Broad Field of Study, Ontario, 2011-2021

Université de l’Ontario Français is in Deep Trouble

Last year, l’UOF managed to attract 19 applications from secondary school student across the province, of which exactly two were first-choice (in the end, three students from this pool ended up as confirmed students). We don’t know how many first-choice applications there were this year, because of the new way OUAC is releasing data, but we do know that the total number of applications received was just fourteen, five less than last year.

Now, I am sure that the institution’s backers will be quick to point out that “105” applicants (a catch-all code for everyone not applying from an Ontario secondary schools, including mature students, out-of-province students and international students) will make up the difference. Last year, the school managed to pick up 145 students from these sources; there is no data on the breakdown of these students but my understanding is that most were international students. No doubt the same will be true again this year.

The issue is not whether UOF is in imminent danger of financial failure – the feds will keep it afloat until 2024. But when federal funding runs out and the full burden of running the institution falls back on the province, the university may find itself in trouble, because the emerging institution is not the one the province thought it was backing when it agreed to fund the project five years ago. Then, the commitment was that in the second full year of teaching the student body would be 85% domestic and only 15% international: that is to say, it was meant to be a francophone university for franco-Ontarians.

That’s quite clearly not where this institution is headed; rather, it is becoming an institution run by franco-Ontarians for the benefit of an international student audience. For whatever reason (and Le Devoir’s Étienne Lajoie does a great job describing the issues here), the franco-Ontarian community is simply not backing this institution in the way it counts – with enrolments. One bad year can be dismissed as a fluke, bad luck, teething troubles, whatever: two bad years suggests a bigger problem. The Lajoie article quotes UOF officials suggesting they should be judged only after 10 to 15 years: I have a feeling they may not get that much time.

Laurentian applications down 43.5%

This is not really a surprise. Last year’s applications came in before the insolvency declaration: actual enrolments ended up at 30% below the previous year because many students who were accepted simply said “no thanks” after hearing about the institution’s financial situation. Plus there are somewhat fewer programs at Laurentian to which students could apply, which would depress applications still further.

So don’t think that a 43.5% decline in applications as necessarily heralding anything much in terms of actual enrolments. The institution will almost certainly accept almost everyone who applies, and it will be as aggressive as possible in its use of incentives to maximize yield. It’s not impossible (though it is unlikely) that we will no drop in new enrolments. This would still result in a reduction in total enrolments because the graduating cohort will be bigger than the entering cohort, but if it happens it will still be a positive result.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post