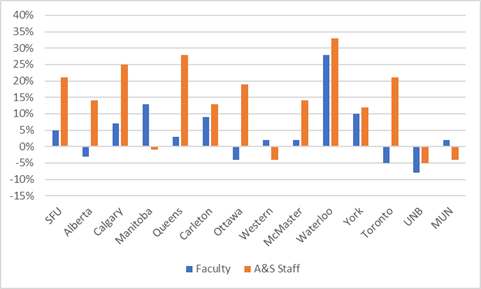

One of the great things about Twitter is the quick feedback about things. And last Wednesday, when I posted the graph below, people started banging on right away, saying “Yeah! Right on! Administrative Bloat!”

Figure 1: Percentage Growth in Academic vs. A&S Staff numbers, Self-Selected Institutions Which Actually Publish Staffing Data, 2010 to most recent year available

Nobody took me up on the offer about how to think about that graph in connection with what I had published the previous day:

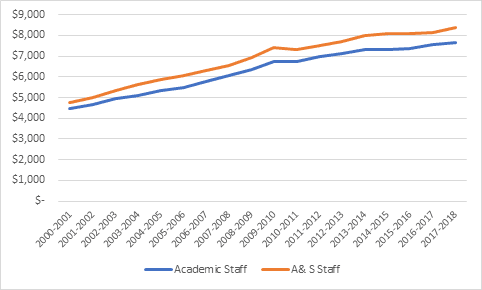

Figure 2: Total Wage Compensation to Academic and A&S Staff, 2000-01 to 2017-18, in millions of constant 2017 dollars

Which is to say that if the first graph (which says that non-academic staff numbers are growing three times as quickly as academic ones) is true and generalizable to the rest of the country, then the only way to reconcile it with the second graph (which comes from higher-quality data and says academic and non-academic staff aggregate wages are growing at comparable rates) is that average wages among academics have to be increasing a lot faster than wages in among staff. In fact, average wages for staff pretty much have to be falling for both to be true – that is, most new jobs are probably at fairly junior ranks. Which decidedly is not what public opinion thinks is happening.

But leave all that aside for a bit. Let’s assume the first graph is right and the second graph is wrong. Is this necessarily a sign of universities going to hell in a handbasket?

For the average prof, I suspect the kneejerk reaction is “yes”. But then, when you point out that a lot of those “admin” people are in fact in places like student services, IT, etc., they usually concede that yes, some of that money at least may be well spent. Indeed, some then talk about how government or tri-council regulations are requiring more form-filling and bureaucratization, and so even though that’s a waste, it’s not the university to blame per se.

I am not sure that the form-fillers are a big deal in macro terms; they exist, but I doubt that’s a big source of employment. I suspect – can’t quite prove it because the data isn’t good enough – that what’s really happening is marketization. There’s a lot more money out there for institutions to chase than there used to be; the issue is that you need to spend money specifically on things that look like “waste” in order to obtain it.

Here’s the way to think about it. Let’s say fifteen years ago you were a president with a budget of $500 million. Then someone says: “you can earn up to another $250 million by concentrating on your image and presentation style to attract new overseas students, rich donors and really big research infrastructure”. If you were a president, how much would you increase your budget in order to tap this new source of money?

That’s a really hard question to answer. No one is saying “if you put in $100 million, you’ll get back $150 million”: that would be too easy. The bargain, as posed, is essentially: put in dollars and you will likely get a positive return. Most institutions do and that’s why most universities are growing, albeit slowly (and, from some faculty members’ POV, often invisibly because it’s not happening in their department and so must not be happening at all). In terms of the thought experiment above, what’s usually happening is that they are spending $100 million extra and getting back $110 million. Which is an excellent rate of return in business. But if you only do the analysis by looking at the composition of the spending side of the equation, then what you see is “administration gone mad”. Doubly so if, like most universities, you can’t be bothered to break out the data by function and just lump all these people together as “staff”.

There’s no question that this more marketized and competitive system generates more “non-core” activity than the old one. It would, from one perspective, be more efficient if someone would just come down from heaven and write universities a cheque for $15 million instead of having them spend an extra $100 million in order to raise $110 million. But that’s the world we live in: not enough people trust government just to hand over an extra $15 million to agencies with weak public accountability mechanisms (come on, you know it’s true), and so we go through this other rigamarole to chase dollars. And yes, it’s an arms race – you can’t not participate because you’ll just get steam-rolled by those who do. C’est la vie.

If there’s a debate to be had, it’s about how effective all this non-academic spending is. My suspicion is that this varies significantly across institutions. For instance, the one area where I absolutely see institutions beefing up is in external relations – fundraising in particular. But is institutional income rising as a result? In some places yes, others no. Nationally, donations to universities are basically flat over the last decade or so, and 2017-18 was a terrible year, with total donations down almost 7% from the year before. So maybe we need to think a little bit more clearly about costs and benefits in these kinds of fields.

Anyways, to sum up: what some see as “administrative bloat” and a diversion of dollars from their “true” scholarly purpose is at least to some degree actually an investment in chasing extra dollars precisely in order to put them to scholarly purposes. The issue is not total dollars but net dollars: if, after spending a lot of money to chase new revenues your institution comes up short – that is, the new revenues serve only to cover the increase in costs and don’t generate surplus for core academic purposes, then you’ve got a problem. Don’t let the raw figures distract you from the actual outcomes.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post