There’s a lot happening in Brazil these days, what with an economic catastrophe, an impeached President, a significant fraction of the country’s political class and business elite under indictment, the return of major gang warfare to Rio and a set of Men’s World Cup qualifying results which suggest that the selecão might not be quite as useless one would think given their performances in their last three tournaments. Meanwhile, there are lots of big stories in higher education, too:

Science With Borders

When then-President Dilma Rousseff launched the program Science Without Borders in 2011, it was like catnip for research universities around the world. Brazil was going to “internationalize” its higher education system by sending hundreds of thousands of graduate students abroad on full-tide scholarships? Bazinga! Cue international offices making frantic efforts to learn Portuguese and making scouting trips to Campinas and Porto Allegre.

It didn’t take long for reality to hit. By 2015, with the Brazilian economy in free-fall, the government “suspended”, mostly to save money but also in response to mounting criticism (from OISE’s Creso Sà, among others) that the program did not represent good value for money due to design flaws. This spring the government dropped the other shoe: the program is being shuttered for good. Given the economic chaos, it may be a long while before we see that many Brazilians seeking schooling outside the country again.

Blame it on Rio

The state of Rio de Janeiro is broke, thanks to a combination of economic depression and the crippling costs of holding the Summer Olympics in 2016. So broke, in fact, that the state is having trouble paying to keep open its public universities. Bills to subcontractors have gone unpaid for months, leaving students without cafeterias. By June they ran out of money to pay teachers, and at the end of July the university shut down indefinitely. Professors, for reasons which I don’t totally understand, chose the day after that announcement to go on strike (obviously, striking if you don’t get paid makes sense, but striking after the term has already been suspended seems like odd timing). School resumed in late August, but pay was interrupted again almost immediately and professors went back on strike last week.

The federal government, which is considering various bailout plans for the state, has told the Rio government to start thinking about privatization and – in the case of universities – charging fees (something the federal government does not do itself at federal universities). Cue the usual inaccurate stuff about how tuition can’t possibly co-exist with access, which is ludicrous because…

Two Million New Students in One Year?

…as we all know, something like 75% of all students in Brazil are in private universities which exist almost entirely off tuition fees (there are a few older Catholic universities which have other streams of income but they’re the minority). If your point of reference for private universities is American 4-year institutions, you might think there is big inequality here, with the richer kids going to private universities and poorer ones relegated to the free public ones. But of course that would be wrong: the free public ones (some of them, anyway) are the prestigious institutions, and with places rationed on academic results, it’s the kids from better-off families who tend to predominate. Most studies which have looked at the question suggest that the income distribution in the two systems is either roughly comparable or more tilted to the poor on the private side.

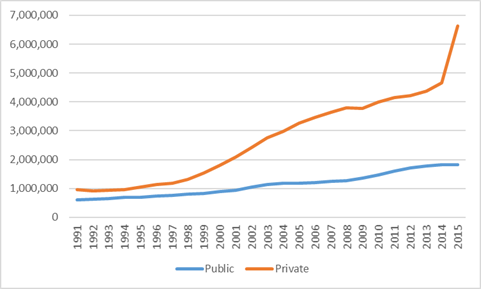

Over the last decade, both left and right governments have counted on private education providers to do the bulk of the work in expanding access. For instance, during Lula’s first term, the government created a program called ProUni, which gives institutions tax breaks in return for providing bursaries for low-income students (at least one for every 10.7 students served). This program was part of the reason behind the remarkable growth in private university enrolments – from 1 million undergraduate students in 1994 to over 4 million in 2010 (for some reason, Brazilians only keep statistics on undergraduate enrolments – data on graduate students is almost impossible to find).

Figure 1: University Enrolments by Sector, Brazil, 1991-2015

Source :Instituto Nacional de Estudos et Pequisas Educacionias Anisio Teixeiras

But if the long-term trend on private education in Brazil is impressive, what happened in 2015 is nothing short of astounding. According to the Institutio Nacional de Estudis et Peguisas Educacionias Anisio Teixeiras, which publishes the country’s most complete set of enrolment statistics, in 2015, numbers in the private sector jumped by just under 2 million students, from 4.67 million to 6.63 million. I half-think this is a misprint, but it seems like an authoritative source and Brazil is just crazy enough as a country that this might actually have happened. If so, it’s a development to watch.

Bom Fim de Semana

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I think there is a mistake in the data used for the graph. Enrollments in the private system did not jump as shown. Official data are:

Year/Public/Private/Total

2014/1,961,002/5,867,011/7,828,013

2015/1,952,145/6,075,152/8,027,297

A possible source for the difference would be to count distance learning in 2015 but not for earlier years.

Best wishes, Renato Pedrosa (University of Campinas/Center of Studies in HEd)