A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a little bit about Nordic countries and some of the trade-offs they consider in order to keep tuition fees at zero when public funding is under stress. I thought I would complement this with a piece that looked at the access side of the Nordic system, both in terms of student aid and in terms of the kinds of access challenges that exist even in a free-tuition system.

To start with student aid: a very useful report came out a couple of weeks ago from the working group for Student Aid in the Nordic Countries (ASIN), entitled Students in Nordic Countries – Study support and economics (in Danish, but Google Translate is your friend). Now in these countries, not only is tuition free but student aid is universal. No messing around with need assessment, which means not only is everyone eligible for assistance, but the amount of assistance delivered is simply a flat allowance, equal for all (in theory, anyway – by my count about a third of bachelor’s-level students in Norway, Sweden and Finland don’t receive any student aid and it’s not clear to me why, though relatively short eligibility periods – that is, the number of years one may borrow – may be one reason).

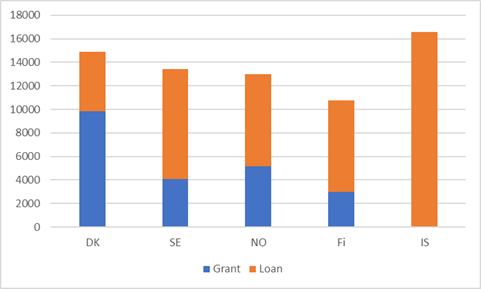

As we see in Figure 1, which shows total aid available to students for a Canadian-style 8-month period of study (the loan amounts are maximums, students are not required to take any loan at all, but it can negotiated up to that amount). What you see is that the Nordics differ significantly with respect to aid. Iceland provides the most ($16,000 per year or so), but it is all loan. Denmark is, by most measures, the most generous with $15,000 in total and roughly a 2:1 grant/loan ratio, though grant aid is taxable in Denmark and so the “net” amount may be slightly lower than that. Norway, Sweden and Finland all provide lesser amounts with loans predominating (28% in the case of Finland, 30% in Sweden and 40% in Norway).

Figure 1: Student Aid Eligibility for an 8-month study period, Nordic Countries 2018

It’s hard to compare these numbers to the Canadian experience because need assessment and provincial variation in programs means Canada doesn’t have a “typical” amount of student aid. But broadly speaking, the Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish packages look a lot like what low-income Canadian students will be getting next year, assuming the Liberals pass their proposed changes to student aid. The difference, of course, being our students pay tuition and theirs don’t.

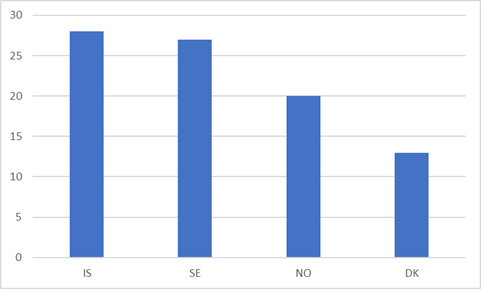

So, this is not a bad deal, right? Free tuition, easy grants, loans, etc. Students have all their needs taken care of, so they must be really able to study hard, right? Wrong. In Norway and Iceland over two-thirds of students have some paid employment during the school year, in Denmark 62%, and in Sweden and Finland roughly half work. That’s about the same as Canada – but in most countries in the region the number of hours worked is significantly higher than the Canadian average, which is around 18 hours per week.

Figure 2: Median Weekly Hours Worked, Among Full-Time Students in Paid Employment

Clearly, the idea that better student aid results in more hours of studying must not be correct, and that many students may be more interested in maximizing income than in studying. But still, that money must be buying something, right? Broader access to higher education, maybe? Fairer life chances?

Wellllll, no, not really. A recent review of literature on access to higher education in Nordic countries suggests that they all have more or less the same problems we have in Canada: students from higher social capital backgrounds more likely to attend post-secondary education. Another study suggests that while Norway and Finland have reduced inequality over the last 30 years, Sweden and Denmark have not; moreover, as in North America, the advantage held by students from more privileged backgrounds is more pronounced in prestige fields like medicine than elsewhere.

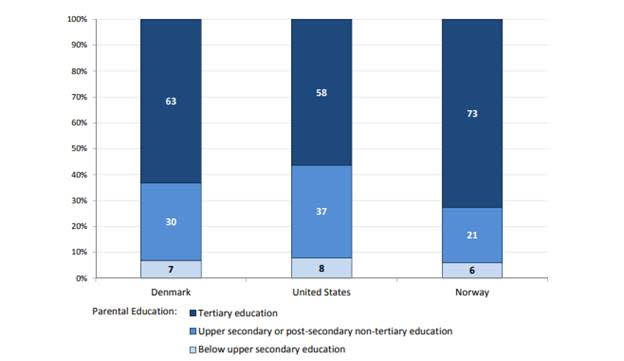

But perhaps the most startling evidence about social background comes from this 2016 paper co-authored by Nobel laureate James Heckman comparing social mobility in Denmark and the United States. It contains the chart below, which never fails to amaze.

Figure 3: Proportion of 20-34 Year-Olds in Tertiary Education, by Parental Educational Attainment

So what does free education – not just free tuition but free tuition with major amounts of grants – buy you? It’s a lot less obvious that you’d think.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The other question is how many get to go to post-secondary

Pretty similar to Canada. Finland a little higher, Sweden a little lower, Norway and Denmark (I think) in between. Not sure about Iceland.

The previous two HESA posts were pretty good. This one, though, isn’t as well reasoned.

One minor point: conflating grants and loans as ‘student aid’ is misleading. We can see this clearly in the stats presentedx where students in countries which offer loans work many more hours than students in countries that offer grants.

A more significant point: citing the educational achievement of parents as an indicator the system favours an elite. This may be true in countries where only a small percentage obtain post-secondary degrees, but attainment in nordic countries is high, so it is not surprising parental achievement would be high.

Similarly, citing reduction in inequality over the last 30 years provides misleading results when looking at nations that started that time period as relatively egalitarian.

Given the overall high standard of living, relatively egalitarian society, and high scores on the happiness index, it’s perhaps not really accurate to say that high levels of student aid doesn’t really buy anything.

Except I didn’t say that. I said it’s not clear what it buys. But nice try.

Right on the money

I wonder if the number of students working, as well as the number not taking student aid, would be a function of a Scandinavian commitment to life-long learning. If a large fraction of students are doing some sort of continuing ed, then they wouldn’t need financial aid, and they’d certainly be working at the same time.

But to answer your concluding question: Free tuition buys a distinction between those privileged in the sense of prepared, coming from families who value education, growing up surrounded by books, etc., and those privileged in the sense of rich. The two groups largely overlap in practice — better-educated parents are, not surprisingly, richer on the whole — but they aren’t, in principle, the same thing.

A hypothetical example: let’s imagine a student both of whose parents spend their entire medical careers working for the Swedish Red Cross in international refugee camps, and never make more than a modest income. Their offspring are likely to be attracted to the same career. (Many children follow their parents). In Sweden, such offspring could go to medical school at any institution, assuming that they’re good enough to be admitted; in Canada, they’d have to win some serious coin in scholarships or take out a loan burden crippling their ability to choose their future careers conscientiously rather than meretriciously.

That’s what free tuition and universal student aid buys. One might call it true meritocracy, or simply a (relative) freedom from financial considerations in pursuing the life of the mind.