Two Thursdays, two big reports out of St. John’s. The first was a 355-page doorstopper on the post-secondary system; the second is the Report of the Premier’s Economy Team, snappily-titled The Big Reset, which broadly covers the province’s entire economy and government in a mere 342 pages. I’m guessing this second report will have a bigger impact on the province’s post-secondary system, so it’s worth looking at what it says. But first, a quick backgrounder on the province as a whole.

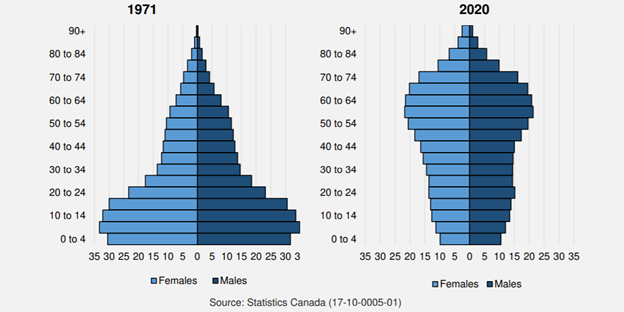

Newfoundland and Labrador is a difficult province to run. Greater St. John’s makes up about 40% of the province’s population, but the rest is scattered in a unique way. The next three biggest cities combined (Corner Brook, Grand Falls-Windsor and Gander) equal less than 10% of the provincial population. The other 50% live in communities that are smaller than 10,000, and most in communities smaller than 5,000. And it’s not compact: those communities are scattered all around 10,000 km of island coastline and across Labrador. Providing services like health and education to a province like this is incredibly expensive, and as a result Newfoundland has the highest program expenses per capita of any province in the country. Plus, due to outmigration, the province’s age-pyramid is simply brutal: health care costs are rising inexorably, and there are fewer and fewer young people to pay for it all.

Figure 1: Newfoundland and Labrador’s Population Pyramid

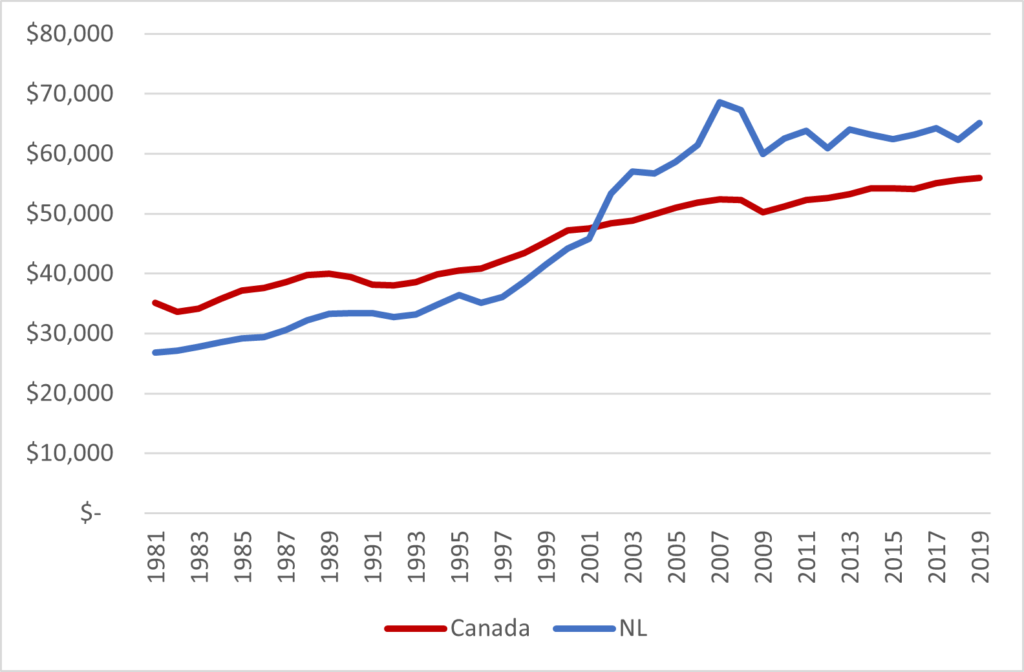

The province spent its first fifty years or so in Confederation as a have-not province. Then, after 1997, when offshore oil went into serious production, GDP per capita rose by a head-spinning 90% (this wasn’t all good news: part of the increase in GDP per capita occurred because the population base shrunk by about 10%). Suddenly, the province zoomed into “have” status.

Figure 2: GDP per capita, Canada vs. Newfoundland and Labrador

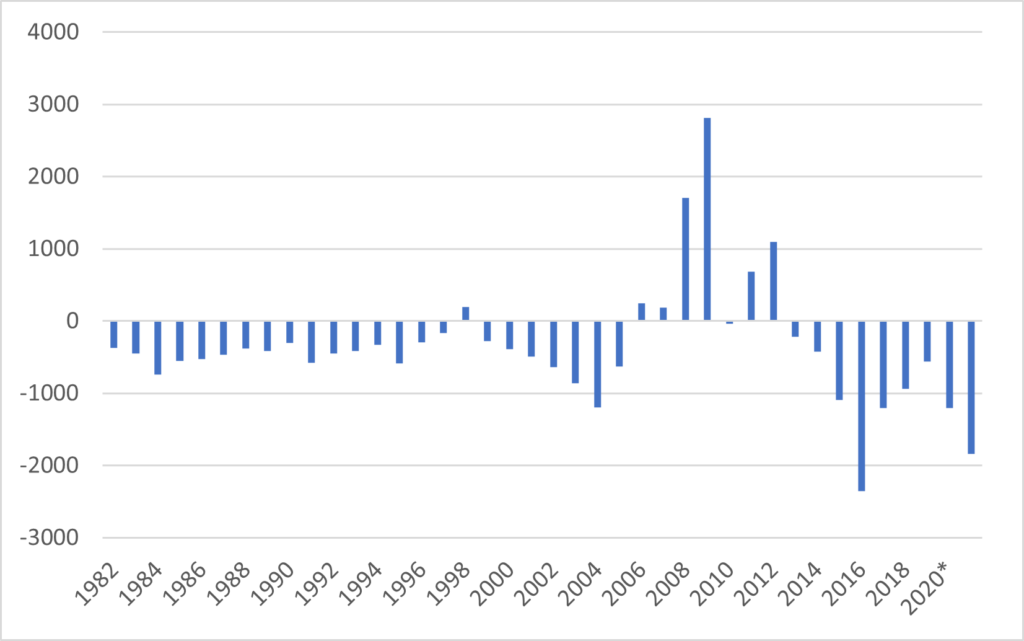

Those good times translated what had been decades of constant governments deficits into a brief period of plenty, as shown in Figure 3, below. Suddenly, instead of running deficits, the province was running massive surpluses. And not only was it running such surpluses, but it was also expanding the size of government: public spending went from about $5 billion a year to $8 billion a year in this period. Times were good…until they weren’t. The whole thing rested on the price of oil staying north of $100/barrel, which stopped about seven years ago. Since then, it has been nothing but record deficits (technically there was a surplus in 2020, but only because they had to book 30-odd years worth of revenue from the Atlantic Accord, a oil-revenue sharing deal with the federal government, all at once: the underlying deficit was still over a billion dollars).

Figure 3: Budget Balance, in millions of $2020, Newfoundland and Labrador, 1982-2021

And, of course, the less said about the billions of dollars lost on the Muskrat Falls project, the better.

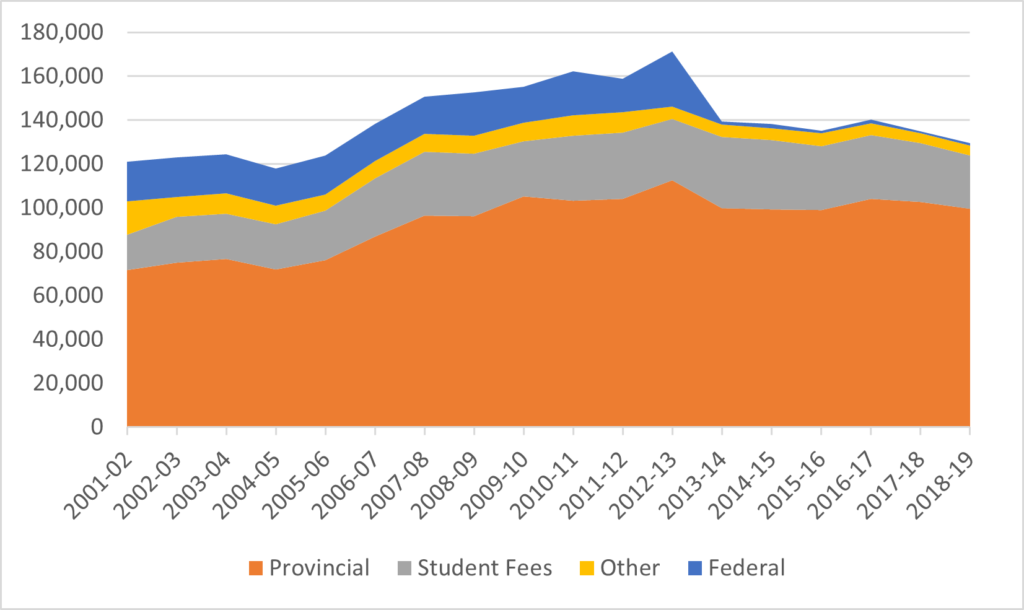

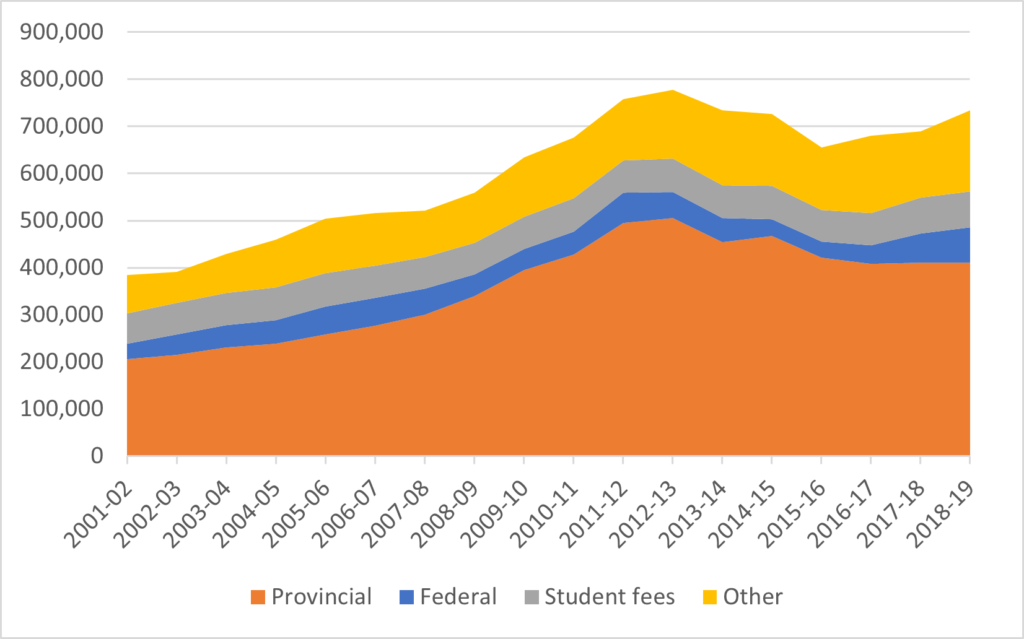

Now, how did this all play out in post-secondary education? At the College of the North Atlantic, provincial funding grew by about 57% in real dollars between 2001 and 2012, before dropping by 13% in 2013 and then staying roughly even since then. Student fee revenue makes up about 18% of total fees, which is slightly more than what it was in 2001, when the tuition fee freeze began. And if you’re wondering about the big drop in federal funding, I’m guessing that has to do with a change in the way EI payments for college-level training were recorded.

Figure 4: Community College Funding in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2001-02 to 2018-19, in thousands of $2018

Over on the university side, the rise and fall was more dramatic. Here, government funding rose by 150% in real terms between 2001 and 2012. Basically, the province turned a firehose of money on Memorial University (though note that in Newfoundland, some of this money is flow-through to hospitals because of a weird funding arrangement for clinicians, so it may not all have gone to the educational enterprise). Since that peak, real government funding has fallen off by 20%, though the university has compensated somewhat by increasing self-generated revenues and obtaining new money from the feds (it seems to be mostly SIF money for capital improvement). That might sound like a win – after all, provincial grants still are twice what they were in 2000 – but of course when universities get money, 70% goes into salaries, much of which is impossible to get off the books because of tenure (short of pulling a Laurentian, anyway). Student fees now make up barely 10% of total income.

Figure 5: University Funding in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2001-02 to 2018-19, in thousands of $2018

Ok, so that was a long backgrounder, but it makes the summary of The Big Reset simple. The province is broke and getting broker. With a structural deficit of $1.2 billion, the province is borrowing over $2,200 for every citizen every year. During that weird period last year when oil prices briefly went negative, financial markets stopped buying Newfoundland bonds. It is not clear how long the province can stay solvent. The Big Reset suggests a lot of things to reboot the economy, but the big one is this: close the budget gap in five years, using a 65-35 combination of expenditure reductions and new taxes. Those expenditure reductions can basically be summarized as: a 25% reduction in payments to Regional Health Authorities and a 30% cut to Memorial and the College of the North Atlantic. That works out to a cut of $16.6 million to Memorial every year from 2022-23 to 2026-27, and of $4.3 million to the College of the North Atlantic. To compensate, the report suggests giving both institutions greater leeway to increase tuition fees.

What would it take to make the books balance without any cuts? Well, at Memorial, it would mean roughly doubling tuition fees. Which sounds absurd, until you realise that Memorial’s tuition fees (net of ancillary fees) are only about $3,000 and that it could double tuition and still be below the national average. For international students it could triple fees and only barely meet the national average. Obviously, one needs to worry about access, though as I noted a couple of weeks ago, the effects of fees on demand are often over-estimated, especially where loans are available (though this requires that the provincial government re-invest in student financial aid, something it cut significantly in 2017).

For the College of North Atlantic, it’s more complicated because, for a variety of reasons, community college students are usually more responsive to fee hikes than university students: it’s not clear that CNA would actually be able to recoup this money entirely from fees. Cost reductions are almost certainly on the cards there instead, mainly through the closure or re-purposing of campuses.

While there is no guarantee that Newfoundland’s newly-elected government will adopt the report in its entirety, my guess is that what shows up in the provincial budget next month is going to be pretty similar to this. It’s going to be a heck of a change, and no doubt a painful one. But with some luck and hard work, it’s do-able.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This seems a terrifying example of the inability of universities — and of the governments which support them — to prepare for bad times by wisely putting money aside in good times. When things were going well, they could have endowed rather than expanded Memorial, or at least paid off any of its mortgages, while doing maintenance in advance.