To Winnipeg, where the provincial government suddenly seems to be taking postsecondary education seriously. Yes, recent years haven’t been great – a vindictive Premier ousting a fantastic college President because he used to work for the NDP, or mooting a cut in post-secondary finances so nonsensical that even the Province’s overwhelmingly Tory business community told the government to get real, thus forcing a U-Turn.

But now the government seems to be heading down a different path. For starters, it has pulled postsecondary education out from under the Education Ministry and created a new post for Advanced Education, Skills and Immigration (which could definitely act as a “Ministry of Talent” if it was given proper leeway). In charge of this Ministry is Wayne Ewasko, who probably should have had this portfolio all along since he was an above-average critic for this portfolio when the Conservatives were in Opposition prior to 2015. And as of last week, a new policy to guide this Ministry called “Manitoba’s Skills, Talent and Knowledge Strategy” was released. (The guide is a strategy for the province across a range of portfolios including immigration, not just the post-secondary sector).

So, what’s in this strategy? Here’s the heart of it, from the Executive Summary:

In Manitoba, we need more students accessing and completing post-secondary education. We also aspire for all university and college students to have work experience included in their course of study. Students who connect to employers while pursuing their studies will move quickly into employment upon graduation. We want students to connect to good jobs and stay in Manitoba.

This is a pretty ecumenical statement: greater access, better skills, more prosperous Manitoba. But the question is: how is the system supposed to get there? Well, the strategy has four “high-level objectives”, to wit: i) anticipate skills needed for the future, ii) align education and training to labour market needs and help students succeed now and in the future, iii) foster entrepreneurial and innovative skills and iv) grow, attract and retain talent.

My take on all this is two-fold. The first is that if you take time to read the whole document, you’ll find its crafting very skillful. And the second is that the first of the high-level objectives is less than fully-baked.

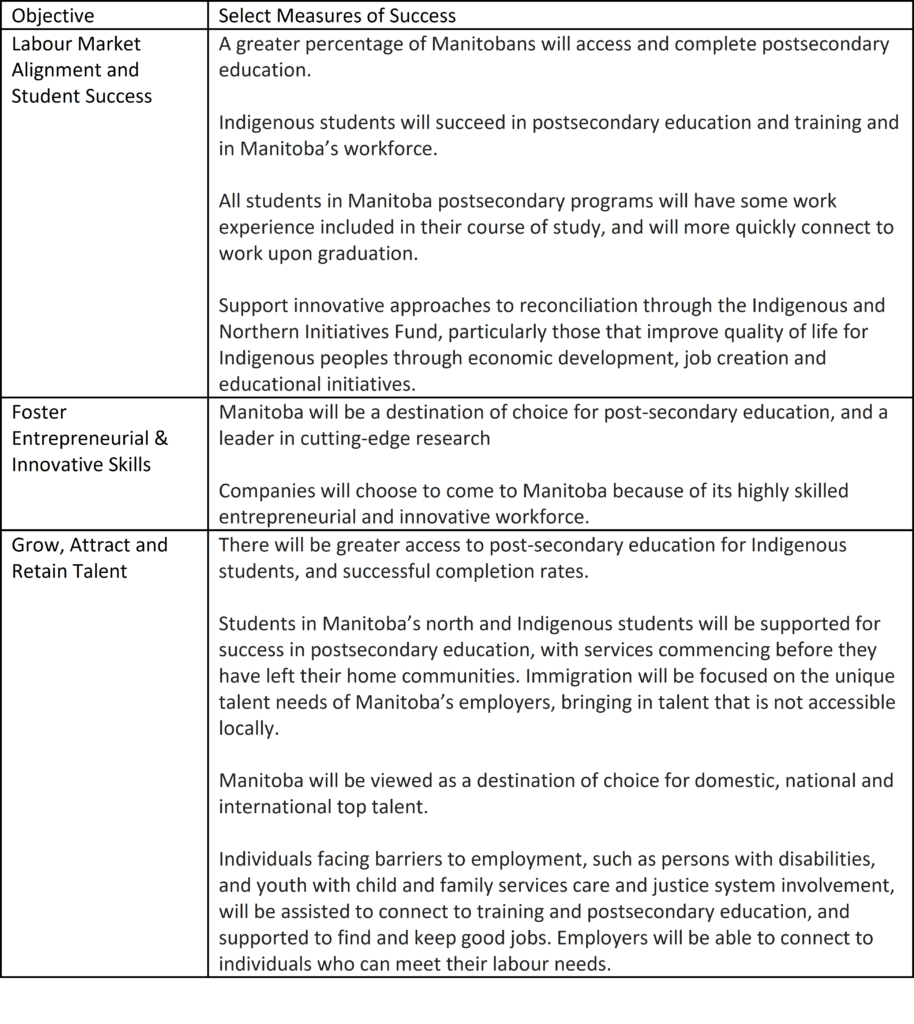

First, on the crafting. There is no doubt at all that the objectives – particularly the second and third ones – are worded in such a way that will appeal to a more right-of-centre audience, and undoubtedly the academic left (which is always irrationally snotty at the use of the words “skills” and “labour market” in relation to education) will do that sneering thing they often do. But if you bother to read the full document, you’ll realize that the headlines and the actual goals are somewhat different. In the table below, I look at the last three objectives and note some selected measures of success.

There is a lot of stuff in here that is highly desirable not just from a Conservative point of view, but also from a Liberal or NDP one. I mean, I get that opposition parties are going to oppose because the Westminster system requires a certain amount of belligerent affective posturing, but a fair reading of this policy shows that could actually be the basis of a long-term, trans-partisan strategy for the province. There’s plenty of room, of course, to be skeptical about some of the short- and medium- term measures the government wants to adopt in pursuit of these goals (partly because many of them are pretty vague). But at the big-picture level there is not a lot here to dislike.

Where I think there is likely a problem – and it is not a huge one, to be honest – is in the stuff around anticipating future skills needs and getting institutions to be “nimble” in responding to shifts in demand. First of all, there does not appear to be any acknowledgement that the Manitoba government itself, and the archaic way it approves programs (or program cancellations) is a significant part of the problem. Second, the document is vague about how forecasting can improve. Governments of all stripes seem to have a limitless faith in the power of “better labour market information”, but frankly it’s really hard to generate and I don’t see any bright ideas in here for how to do it better. Businesses themselves are a really weak source of information, as I and my colleague Yves Pelletier observed in our Review of Manitoba Colleges a couple of years ago: Manitoba is awash in small and medium businesses which don’t have a lot of spare capacity to think even medium term about their evolving skill needs. I am pleased to see that the document also refers to postsecondary institutions’ capacities in terms of looking at trends in skills and technologies, which I think are an important part of the equation, but still overall, I worry that this path leads to over-reliance on some relatively dodgy quantitative methods for looking at ill-defined skills shortages.

Still, this is fixable and shouldn’t detract overall from the bigger picture, which is that this is a reasonable and sustainable approach to skills and talent, and one which seems to have the backing of the province’s postsecondary institutions – check out the Minister’s press conference launching the document here and speed through to 9:45 to see all the province’s university and college Presidents talking about how their institutions already live the values of this report (btw, Mark: great shirt!).

Overall verdict: room for improvement in terms of detailing actual initiatives, but overall a pretty good effort, and one which hopefully can find support across the political spectrum and serve as a basis for long-term policy stability even if a new government is elected. I can think of at least one other Western province which would have been a whole lot better off with this approach than the one it took.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post