Today I want to go back to that COU report on academic staff I described yesterday (mind-blowing because of how much previously unavailable data it provided) and pick up on the other set of issues it raised: namely, the status of part-time and non-tenure track staff (ie. sessionals). The data is not perfect, but it is by several orders of magnitude the best thing ever published on the subject. So here goes.

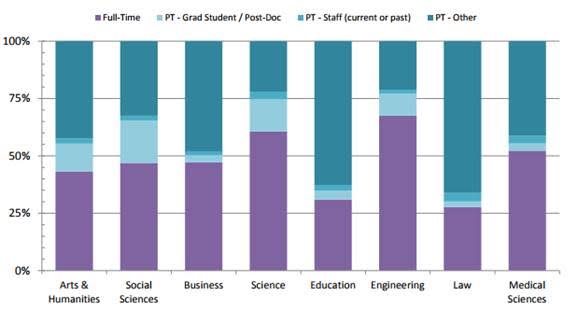

The report makes a distinction between tenure stream professors (42% of all instructors), full-time non-tenure stream (6%) and part-time instructors (52%). This mix varies quite a bit across faculties. The proportions of FT to PT is highest in Engineering, and lowest in Law and Education. The composition of PT faculty also varies substantially across fields of study. In no faculty do grad students and post-docs form a majority of the PT population; however, they come closest in Science, and they make up a substantial proportion in both Social Sciences and Humanities. They are essentially non-factors in Business, Law and Medicine.

Figure 1: Distribution of Full-and Part-time Professors by Field of Study

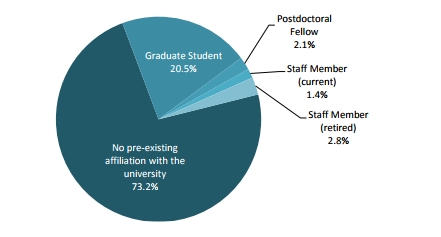

In fact, across all areas of study, only 23% of part-timers are actually grad students. Another 4% are either current or former faculty members (part-time status is sometimes a way of easing into retirement). The remainder are described as having “no pre-existing relationship with the university”.

Figure 2: Part-timers by affiliation with the University

With respect to qualifications, the report notes that only about 35% of part-timers hold a PhD and maybe 2% have a professional degree: the remainder have Master’s Degrees or lower (among full-timers, over 90% have a PhD). But that 60% plus without PhDs are a pretty mixed bag. Obviously a third of those are grad students, and in Education, Nursing and Business they are probably professionals with on-the job experience. But without being able to cross-reference the tables, it’s hard to know how to interpret this data.

There is also an interesting attempt to try to try to knock down a persistent strawman in the debate about sessionals; namely, that all sessionals are wannabe profs and why don’t we just expand the ranks of the full-time professoriate, dammit (see, Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations, among others)?

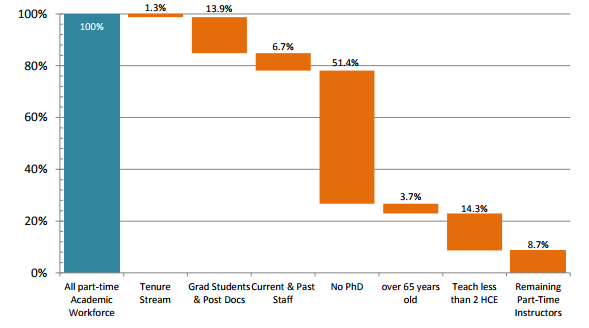

The data here is based on a smaller sample of institutions – just the six (we don’t know which ones) who were able to provide data on 80% or more of their PT staff (meaning it’s an incomplete and potentially biased sample to start with). I think it’s fair to say this data is probably not as reliable as the stuff in the rest of the data in this document. But it’s still interesting, and still better than pretty much any other data out there, so let’s have a look.

Figure 3: Summary of Part-Time Instructor Composition

Figure 3 is a waterfall graph, meant to parse the various components of the part-time academic workforce and show why most of them don’t fit the stylized picture of the sessional-as-wannabe-full-time academic. Basically, if you take out the 1% of Part-timers who are actually tenure stream, the 14% who are graduate students and post-docs (remember, this is a different set of institutions, so it’s 14% here and not 23% as in figure 1), and the 7% who are current and past staff, and the 51% who have no PhD and the 4% who are over 65 years old (and hence presumably not looking for a full-time gig), what you’re left with is just 23% of part-timers who might fit the stereotypical description. And of those, fewer than half (8.7% of the total) are teaching more than one course at the moment and so might be said to be trying to eke out a living through sessional work.

I think this is a fair attempt to refute the idea that there are lots of people who a) want to be profs, b) have the qualifications to be profs and c) are actively making a (poorly paid) living through sessional teaching. But it’s not a good way to measure people who might want to be profs and are being shut out: many of those with fewer than two courses might take more courses if offered, and a fair chunk of the grad students and post-docs may be aspirants to prof status as well.

In any case, once again huge kudos to COU for doing this work and making the data available. It’s a major contribution to better understanding staffing patterns in Canadian universities.

And to all those universities outside Ontario who haven’t yet published similar data: what are you waiting for?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Alex as one of these people who “) want to be profs, b) have the qualifications to be profs and c) are actively making a (poorly paid) living through sessional teaching”, whose existence you are actively trying to refute, it’s hard for me to be objective here.

I do grasp the logic of flexible labour that’s driving the dwindling number of full-time faculty, but can we not ask some broader questions about long term costs and consequences of the academic caste system? Precarious part-timers like me trying to continue research without funding (nevermind knowing whether I’ll be working in three months); burned out TT faculty; a narrowing of research agendas with resources concentrated in the hands of TT rockstars; the social costs of over-producing graduate students who then can’t use their skills; the quality of student learning. Just because these things are hard to measure doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

It’s also just an unkind system. I know no one gives a shit about kindness over data, but we work with students who not only need support academically, but are often also are struggling to find a place for themselves and establish adult identities under conditions of profound economic and social uncertainty. Neither TT nor precarious faculty have the luxury of contributing to the sense of community that restores tired, overworked colleagues and gives students a secure intellectual and emotional foundation upon which to develop as young adults.

Unis and colleges are Employability Factories. No one is happy. And that sucks.

Laura

I’m wondering if non-tenure track staff in the Medical Sciences disciplines, many who don’t hold a PhD, are overly influencing the results that we are seeing.in Figure 3. It would be interesing to know whether the profile for Graph 3 is similar across disciplines and perhaps the total number of staff reported under each major discipline.