To Winnipeg, where the University of Manitoba Faculty Association (UMFA) has gone on strike for the second time in five years. It probably won’t be the last institution to see labour action this year (see Ken Steele’s very good round-up of boiling-over labour issues here). The main issue is over money. UMFA’s central claim is that its members have lower salaries than anyone else in the U-15 and that over the past few years UFMA have lost approximately 8% of their wages due to inflation. Combined, this makes it difficult to recruit and retain faculty. Hence the labour action.

Of course, the union would say something like that, wouldn’t it? The question is how accurate the claim is. Thankfully, this is one area where Statistics Canada data is surprisingly complete and up-to-date. One can go quite deep into the weeds in this area. So, let’s do it.

(Before going further, I should stop to note here that in this blog post the “rest of the U-15” is a weighted average, not an institutional average of 12 other schools. Université de Montréal and Université Laval are excluded because their data is incomplete. Also, note that for the rest of the blog I am dealing with averages not medians. Use of institutional medians would give one slightly different numbers, but would not substantively alter the following analysis.)

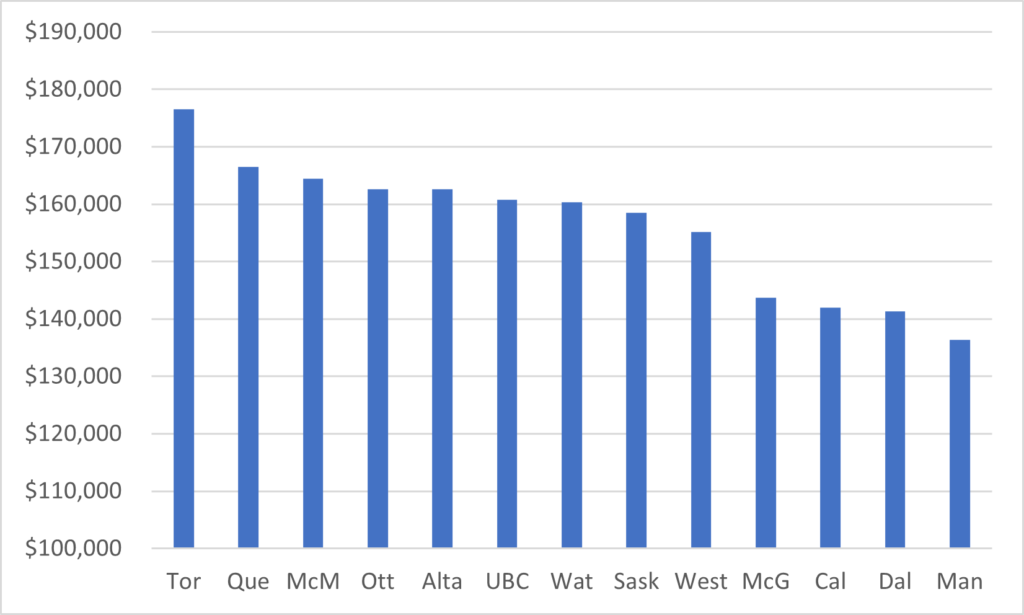

There are certainly salary gaps and University of Manitoba is indeed bottom of the pile. It’s not uniformly bad – for associate profs, U of M comes ahead of a clutch of other universities, including Dalhousie, Alberta, Calgary and McGill. But overall, U of M is, as UMFA says, home to the lowest salaries by far. Part of it is because Manitoba isn’t very rich and doesn’t spend that heavily on higher education and part of it is because Winnipeg is a comparatively cheap place to live. Some of you may recall a few years ago I expressed professorial salaries as a function of housing costs: if we used that as a measure, University of Manitoba would be very close to the top.

Figure 1: Average Annual Salary, all named tenured ranks combined, by institution, 2019-20

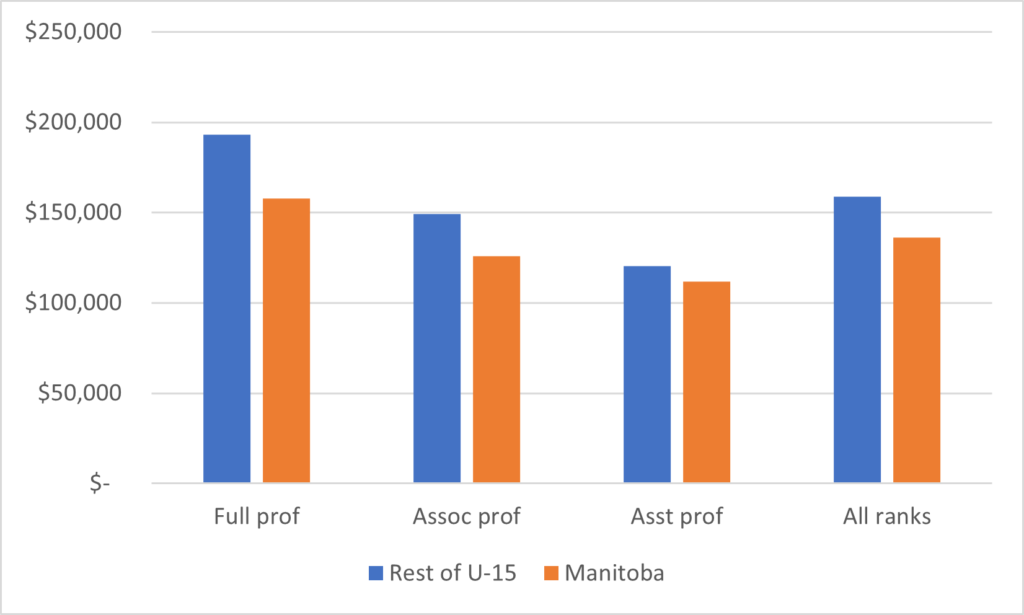

And here’s the data comparing average salaries by rank.

Figure 2: Average Annual Salary for tenured/tenure track staff by rank, University of Manitoba vs. rest of the U-15, 2019-20

So, UMFA has a point about U of M profs being the lowest paid, even if conceivably you could add some nuance to that here and there. But are things getting worse? To check that, we can re-do figure 2 but focus only on real (ie. after inflation) changes in salaries. As Figure 3 shows, across all ranks, professors in the rest of the U-15 saw increases of about 2.6% between 2014-15 and 2019-20 (the last year for which data is available), while professors at the University of Manitoba have seen reductions of about 1.7%. This suggests that a growing gap is a problem.

Figure 3: Real Change in average salaries by professorial rank, 2014-15 to 2019-20, University of Manitoba vs. Rest of U-15.

But a closer look at this data is warranted. A substantial portion of the gap is occurring because of the fall in real salary of full professors. If the problem were simply about the way the salary scales have been frozen over the last couple of years, the gap should be no higher at the top ranks than at the bottom ones. What’s happening here is one of two things: first, it could be that older professors at the top of the salary band are retiring, thus lowering the average payment for this group. Or, second, it could be that older professors are hitting the salary maximum and ceasing to receive annual raises (not all institutions have salary maximums, but Manitoba is one of them). The root cause here is that Manitoba had a lot of old professors about five years ago and one wat another, whether they are staying or going, it is their behaviour which is driving the big change in salary numbers.

Either way, UMFA is on to something: professors at U of M are the lowest paid (though this has something to do with Winnipeg’s cost of living) and they are falling further behind the institutional average, even if it is perhaps not as quickly as being made out and it is to a certain extent being driven by the oldest cohort of faculty members. In other words, we can argue a bit about the magnitude of the problem, but overall UMFA has a case for action on salaries.

The main talking point in the negotiations though, isn’t the salary offer: it’s about how the provincial government chooses to regulate institutions. Back at the time of the last strike in 2016, the Conservative government basically told the institution to hold the line on salaries. Though it did not have a legislative framework to lean on, it did what the government of British Columbia has done since time immemorial and told the institution that it could negotiate any deal it liked up to a certain amount (in this case 0%). The university had little choice but to agree to this and the strike ended in failure, even though the courts later said that the province’s move amounted to unfair interference in collective bargaining. So, the main talking point is “no provincial mandates”, “let U of M bargain independently” etc. All on the theory that if the province weren’t involved, then the university would be munificent with its riches.

This last point seems to me to be slightly wishful thinking. Yes, the university posted a big surplus last year. A substantial portion of that surplus was research funding – some of it I believe one-time – from the federal government that really cannot be used to fund operations. Plus, the provincial government is running a $1.5 billion debt, suggesting that cuts to funds are almost certainly on the way in the near future and the institution is well within its rights to be cautious about increasing its cost base too much.

Still, the fact of the matter is the two sides aren’t that far apart. The union wants a two-year contract in which salary scales would increase by 2.5% each year: the university is offering something a bit more complicated but which amounts to 50-60% of what the unions is asking for, if I understand the math correctly (kudos, btw, to the University of Manitoba for publishing a comprehensive guide to the state of bargaining, available here – more institutions should do this). Adding another 2-3% over two years, including all the impacts on pensions, etc. is probably in the range of about $3-4 million.

The two parties should split the difference and end the strike. A long strike over a gap this small would be silly.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thanks for this analysis. The links don’t seem to work.

Apologies, the links are updated now.