Whenever you hear somebody complaining about higher education funding in Canada, it’s usually only a matter of time before someone says “why can’t we be more like Scandinavia?” You know, higher levels of government funding, no tuition, etc., etc. But today let me tell you a couple of stories that may make you rethink some of your philo-Nordicism.

Let’s start with Denmark. The government there is trying to rein public spending back in from a walloping 56% of GDP, and bring it back down to an only slightly less-imposing 50% by 2020. And it’s doing this while the economy is still weak, and while oil prices are falling (Denmark has some North Sea oil so, like Canada, it tends to see low oil prices as a negative). So cuts are on the way across many services, and higher education is no exception: universities there will see cuts of 2% in their budgets for each of the next four years. Over to Finland, where it’s the same story in spades. Nokia as a technological saviour/massive boost to government coffers is long gone, and economic contraction in Russia is hitting Finnish exports hard. With the economy declining and the government trying to stay out of debt, the government there also laid out cuts to many services, including higher education: there the hit is a cut of roughly 13% out to 2020.

Now, in North America, when you hear about cuts like this you tend to think “oh, well, at least the government will let institutions make some of it back through tuition, either by increasing enrolment, or raising fees, or both”. And in general, this attenuates the impact of funding cuts (unless of course you’re at Memorial in which case you are plain out of luck). But remember, these are free-tuition countries. By definition, there is nothing that can attenuate the cuts. And so that 2% per year cut for the next four years in Denmark? The University of Copenhagen has since announced a first round of cuts equaling 300M DKK ($62 million Canadian), equal to about 5.5% of the university’s operating budget, and that will involve cutting 500 staff positions. Those cuts in Finland? The University of Helsinki has decided to cut almost 15% of its staff positions.

Total reliance on government looks good on the way up; much less so on the way down. That’s why tuition fees are good. You know students will pay tuition fees every year, which makes them more dependable than government revenue. Fees balance the ups and downs of the funding cycle.

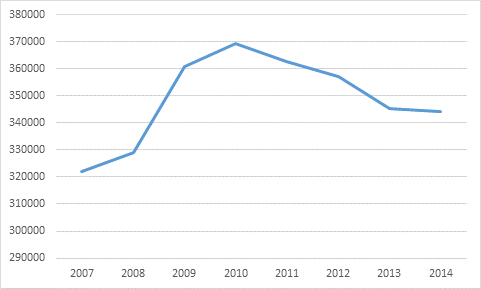

Another thing tuition fees do is to provide an incentive for institutions to accept more students; if institutions can’t charge tuition and aren’t funded according to student numbers, their inclination will be to accept fewer students, thus undermining the “access” rationale for free tuition. And this seems to be the case in allegedly-access-friendly Sweden, where enrolment in first and second degree programs has actually been in decline over the past few years.

Total Bachelor’s/Master’s Enrollment at Swedish Universities, 2007-2014

I know what you’re wondering: is it a demographic thing? No. The 2015 version of the annual report, Higher Education in Sweden (which is a great report by the way… one of those documents you wish every country could publish), makes it clear that the ratio of applications-to-acceptances for students with no previous post-secondary education (i.e. 18-19 year olds) has actually been rising for the last few years (from 2:1 to 2.5:1). And it’s not a financial thing either: between fall 2010 and fall 2014, real expenditures at Swedish universities increased by 12%, or so.

So what’s going on? Well, a few things, but mainly it seems to be that universities prefer to get more dollars per student than actually increasing access. And I mean, who can blame them? We’d all like to get paid more. But I genuinely cannot imagine any jurisdiction in North America – you know, big, bad North America, with its awful access-crushing neo-liberal tuition regimes – where reducing spaces while government expenditures were increasing wouldn’t be considered an absolute scandal. Yet this is what is happening in Sweden, and apparently everyone’s OK with it.

Total reliance on government funding can make universities complacent about access. Fees can incentivize institutions to actually admit more students. Fees have a role to play in access policy. The data from Scandinavia says so.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I enjoyed this post, and hope that it shifts some of the thinking away from the effects of “liberalism” (whatever that’s supposed to mean) to massification, effects also seen in progressive countries and, indeed, in communist regimes.

I would add, moreover, that the above seems a good reason why governments should not fund universities from year to year — thereby making them hostage to the budget cycle and the overall economy — but endow them forever. This would, moreover, provide some of the benefits of a sovereign wealth fund, as a stabilizer on the economy, and be somewhat harder to raid for populist projects.

Did you notice any changes in funding in Norway? I know that it has a ginormous sovereign wealth fund, but does it also endow its institutions of higher learning separately?

1. Isn’t, “admit fewer students and given institutions the same amount of money” the advice Ken Coates was giving last year? Who knew Scandinavia was paying attention. Of course that raises the whole issues of “attendance as a good in itself” vs accusations of diluting standards.

2. Regardless of tuition or not, it seems trivial that governments could simply adopt a per-student funding formula that would make institutions compete to admit more students to get more funding, whether it’s direct from them or indirect from the government on their behalf. That’s roughly how school boards wind up competing with one another, at the primary and secondary levels.