Earlier this month, the Queen’s student newspaper, The Queen’s Journal, reported on what seems to have been an extraordinary outburst by the university’s Provost, Matthew Evans, during a campus Town Hall to discuss cutbacks in early December. During this meeting, the Provost is alleged to have said “I’m concerned about the survival of this institution. Unless we sort this out, we will go under.”

The story was picked up by a number of outlets across the country, including CTV and The Globe and Mail. On social media, there was incomprehension. On the one hand, some were quick to suggest that the provost’s remarks implied that Queen’s might be the next Laurentian, about to fail. On the other hand, a determined bunch of staff members who have banded together under the banner of “Queen’s Coalition Against Austerity” (or QCAA) were quick to point out that in fact the situation might not be as dire as the university is making out (the QCAA case is explained in detail here).

So what’s the real story? Well, it’s complicated. The university is certainly facing a financial challenge the likes of which it hasn’t seen in about 30 years. But it’s genuinely complicated, and the way the university has managed the communications around this issue has not really simplified much. As a result, people seem to be speaking past one another.

Much of the challenge in deciphering what is stems from the fact that at big, research-intensive universities, there is a world of difference between what happens in the operating budget and the overall budget, because the former only constitutes between half and two-thirds of the latter. If you don’t take that into account, you can make some really terrible errors. So, for instance, the QCAA’s claim that the university “has consistently overestimated budget deficits by an average of $44 million a year” is based on the fact that the figures in the year-end financial statements (which cover the entirety of the institution) tend to look better than the ones in the annual Budget Report (which only covers the operating budget). But this is a mistake. What looks to QCAA like overly conservative budgeting is in fact simply the fact that parts of the university are doing just fine. Just not the operating budget.

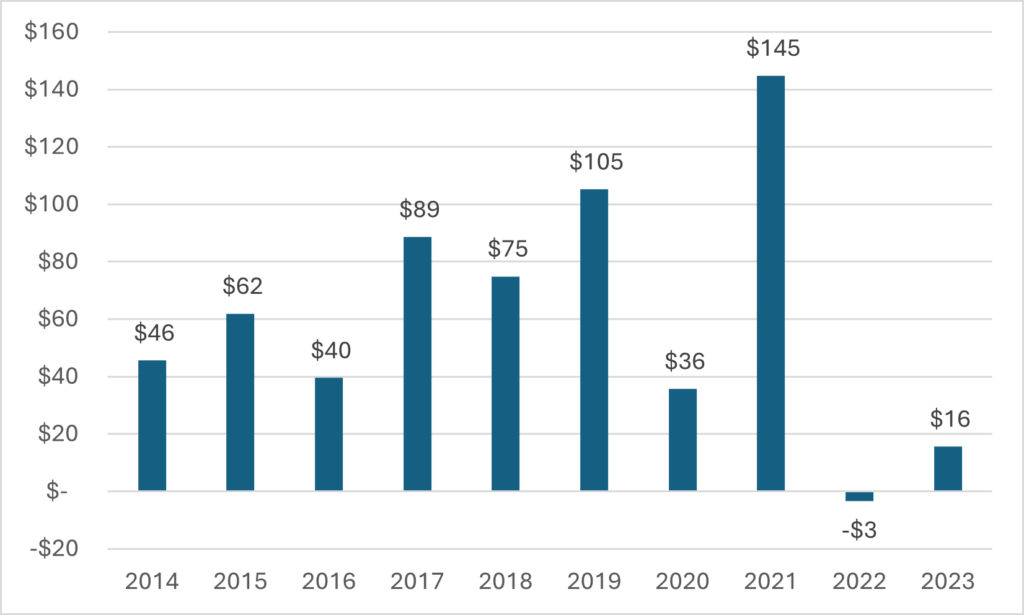

If you only look at the financial statements, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that Queen’s is doing quite well. In the past ten years, only one year has seen the institution post a deficit (2021-22) in the last ten, and the cumulative surplus over the last decade is $608M or so.

Figure 1: Net Annual Financial Surplus, Queen’s University, 2013-14 to 2022-23, in Millions

As a result of these surpluses, if you look at the big institutional metrics, the university looks healthy. It far exceeds key provincial metrics with respect to financial sustainability. Though its debt has grown somewhat in the past decade, its “expendable net assets” (more on this in a second) have grown faster, so that its viability ratio has never been better. In theory, as of last April it had about eight and a half months worth of “expendable net assets”, about twice what it had a decade ago. On the basis of this, a major bond rating agency gave the university a big thumbs up just this spring.

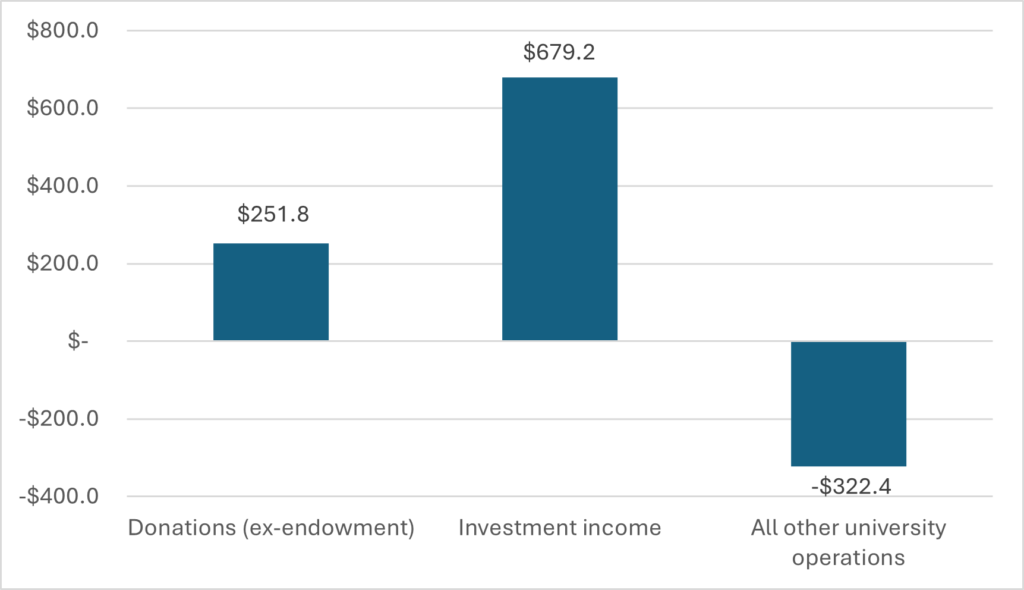

But dig a little deeper and the problems start to show up fast. For instance, as you can see in Figure 2 below, more than 150% of that surplus over the past ten years comes from donations and invested income. The university has been losing about $32 million per year on every other facet of its operations. Now this doesn’t affect the long-term future of the institution quite so much because both “donations” and investment here represent only those moneys which are made available in any given year (i.e., they exclude donations and endowment income which are directed to the endowment). But what it tells you is that the university is unusually reliant on donors and financial wonks to make up shortfalls in the operating budget.

Figure 2: Cumulative Source of Surplus, Queen’s University, 2013-14 to 2022-23, in Millions

(To be clear, you want donations and investment income to enhance your budget. It’s how you get new buildings and have nice things. But ideally, you do that on top of a balanced budget, rather than use that income to cover other operational deficits. Also, I am pretty sure Queen’s is not alone in running its finances this way. I suspect if I went across the U15 probably half of them would have charts that look like Figure 2).

It’s not hard to identify the sources of stress in the operating budget. Over the past five years, total salary mass is up on average five percent per year, or $136 million. Government grants increased over that same period by $5 million and student fees increased $76 million. In other words, the growth in salary costs alone have outpaced the two main sources of external institutional income by $55 million. If there is a similarity between Queen’s and Laurentian, it is that Queen’s has not had a lot of luck attracting international students. These days, it seems as though Ontario universities have difficulty balancing their budgets if their student body has fewer than 15% international students; Queen’s is stuck at a shade over 10% and quite simply that spells trouble. In the case of the 2023-24 operating budget, it means a deficit of $62.8 million (or, in the delightful phrasing of whoever draws up institutional budget, “a balanced budget after the $62.8 million draw-down of reserves”).

At this point the question naturally arises: why can’t the university use more money from the endowment to fund the operating budget? The main reason is that a significant chunk of the endowment is restricted because donors tend to put conditions on the donation be it for scholarships, research chairs, or whatever. Some of the endowment is “unrestricted” and in theory more of that money could be used to cover general gaps in the operating budget, but the thing is that endowments are meant to at least stay stable over time. Raise the withdrawal rate too much and the asset starts to shrink. In fact, withdrawals from the endowment exceeded investment returns three times in the past decade: the big cumulative numbers Queen’s has posted in endowment returns have come from a couple of mondo years where the stock market went wild, mainly in 2021. That’s not to say that more money couldn’t be made available for spending as the QCAA’s is demanding; all it would take is a change to the disbursement rules. It’s just that the margin to do so probably isn’t that large. 2021 does not happen that often.

But what about all those “expendable assets” the university has? By definition they can’t be restricted, right? Well, it’s an interesting question. The term “expendable assets” actually includes all internally restricted endowments apart from capital assets sinking funds for debt repayment, as well as things like departmental reserves. So while Queen’s has something like three-quarters of a billion dollars in “expendable assets”, most of those assets are already spoken for and are in use somewhere in the university or are being set aside for future building construction/improvement or land purchase, departmental reserves, etc. In a pinch, if you were facing the liquidator, might want to prioritize current spending over these future-oriented uses. But let’s not pretend that all expendable funds can actually safely be spent on immediate uses without damaging the institution.

So my view is that Queen’s is not, on the whole, overreacting to its situation. The operating budget needs to come back into balance. There are fair arguments to be had about whether that needs to be done in two years rather than three, the extent to which the balance needs to come through increased revenue or reduced costs (the former is more hopeful, the latter more reliable) and whether there is room to change endowment disbursement policy to reduce pressure on the operating budget. At the same time, talk that the institution is “going bust” is probably unhelpful: deliberate or not, it conjures up images of what happened at Laurentian, and however bad the current operating deficit is, Queen’s simply is not facing the kind of disastrous liquidity position that Laurentian was.

Cooler rhetoric from the administration is therefore called for, but so too is a better public exposition of institutional finances. As I have said before (here and here), universities in general are not good at keeping their staff informed about the realities of income and expenditure. In the absence of such clarity people try to fill in the gaps as best they can, end up confusing operating budgets with institutional financial statements and getting the wrong end of the stick.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

It’s disheartening that consultants promise ways for institutions to diversify their revenue streams, but when it comes to faculty pay and the overall financial health of the institution both can suddenly only be tied to provincial government grants (stagnant) and tuition revenue (frozen in the case of domestic) rather than all revenues. It’s an impressive trick to render a $600 million accumulated surplus irrelevant.

Coupled with last week’s blogs that suggested that university presidents aren’t paid enough and that faculty are childish impediments to change, the intended audience of these blogs is clear. I suppose the message might be different were faculty the ones hiring consultants.

Hi Michael. Glad to see you are thriving at OCUFA.

I suggested university Presidents were not overpaid, which is different from saying they are underpaid. And literally no one in the Brian Rosenberg podcast used the word “childish”. Hope that helps.

“To be clear, you want donations and investment income to enhance your budget. It’s how you get new buildings and have nice things. But ideally, you do that on top of a balanced budget, rather than use that income to cover other operational deficits.”

One can square this circle in another way than by raiding endowments to pay operating expenses: use endowments to endow what would otherwise be operating expenses.

So instead of taking $40 million from investments to cover a $40 million shortfall in operations, use $40 million to create 20 endowed chairs, thereby removing about $4 million dollars (annually, forever) from the operating expenses. One could endow other things, as well, such as building maintenance, landscaping, scholarships, maybe even an acquisitions budget for the university library.

The investment fund doesn’t get spent — in fact, you want it there, earning revenue — but operating expenses gradually go down. It might, however, be better to hive off parts of the endowment fund, setting up separate funds for each of the things being endowed. This would remove the temptation from anyone wanting to raid the endowments for a pet project of some sort, or just to reduce the government grant.

10% return never happens. 5% is about where the philanthropic standard tops out. So $40M in fundraising gets you $2M a year in perpetuity.

I’d have to go back and check, but pretty sure that Queen’s endowment donations (distinct from the money that gets raised and spent in the same year) average less than $30M per year (and therefore would generate shy of $1.5M in earnings). Their costs have been rising at about $32M/year over the last decade. So this strategy might cover 5% of the growth in costs each year.

My apologies. I was guessing at returns, and should have guessed lower. My wider point still stands, however: there is a way to pay for at least some operating expenses from endowments, without running the endowments down.

BTW, in the blog itself, you say that “The university has been losing about $32 million per year on every other facet of its operations.” That seems rather incompatible with “Their costs have been rising at about $32M/year over the last decade” (above), which would produce a deficit of $32 million in the first year, $64 million in the second year, and so forth.

If the operating deficit is only $32 million / year, then converting $640 million (i.e., $30 less than the investment income of the current endowment over the past nine years) into a series of endowments for particular purposes ought to wipe it out. The effect could be achieved by assigning $70 million / year from the endowment income for particular purposes, for about ten years.

This would also have the happy benefit of protecting individual programs, professorships and so forth from whatever provincial official, change agent or Mongol horde wants to eliminate everything not deemed relevant.

(As a further apology, I shouldn’t be so unfair to the Mongol Empire, which patronized artists and scholars).

I have been wondering about this for some time now: What is the Ontario government’s master plan for universities? With all due envy, Queen’s is a first-class university with an excellent international reputation. And it’s not the only one of Ontario’s “academic crown-jewels” that is in trouble. Under-funding its universities in this way is extremely short-sighted, and imposing a domestic tuition freeze on top is outright indecent.

Are there too many universities in Ontario? Are too many students attending university? Does the Ontario government hope for a “consolidation” of the sector through Darwinism? Pray tell! Ontario university employees, students, and the public deserve to know.

It seems to me that the PSE sector is an important industry in Ontario (no frowning, please, I chose that word deliberately – and why not? It’s making a lot of money for Ontario). If one of your flagship universities sinks, that will imply a loss of how many thousand “high-paying jobs” and sink a “whole region into recession”? Ever heard those phrases in other Ontario industries and recalled the reaction? I guess it’s all in whether you love or hate any particular industry.