For reasons that continue to baffle me, the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario keeps putting out quite fascinating research papers with almost no fanfare. Seriously, reading their publications page is the literary equivalent of the sound of a tree falling in an empty forest. Fabulous, fabulous stuff that somehow appears in conditions of near-absolute secrecy.

The latest in the series of obscure diamonds is a piece written by the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation’s Reuben Ford, Taylor Shek-wai Hui and Cam Nguyen, called Postsecondary Participation and Household Income and it mainly does two things. First, it details the evolution of provincial student aid programs and second, it looks at changes in access to post-secondary education by income group. I won’t say this is a definitive paper in terms of student financial aid and access for reasons I’ll outline below. But it still makes an enormous contribution to the Canadian literature in both areas.

The first fifty pages, which catalogues policy changes in student aid programs over the past 20 years will, in all likelihood, be a tough read for most. However, as the author of what is pretty much the only previous attempt to bring order to the comparison of the country’s 14 student aid programs (see pp. 181-218 of my 2004 book The Price of Knowledge co-authored with Sean Junor), I thought it was fabulous. What they have done in this section is an enormous public service. If, one day, Statscan and the various provincial and federal student aid programs could get their act together and actually merge their individual client files with the Post-Secondary Student Information System to create one powerful research data base (don’t worry, not holding my breath, since we all know nobody cares enough to expend the effort), this document will be the bible for figuring out what kinds of natural experiments could examine the effects of small policy changes.

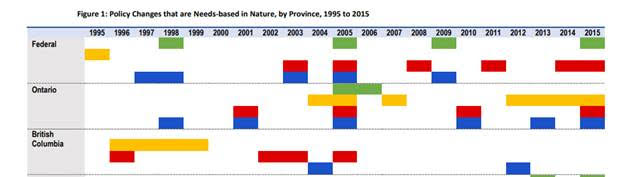

But even without that, the whole section is worthwhile for the super-neat colour-coded chart on p. 51-2 (partially reproduced below), showing the timing of individual policy changes in every province (green for income/need-targeted grants, yellow for untargeted grants or tuition freezes/reductions, red for higher loan limits or lower expected contributions, and blue for indirect measures like loan interest reductions). It’s brilliant.

The second half of the paper uses Census data to look at PSE participation rates by province and family income using census data from 1996, 2001, 2016, 2011 and 2016 (ok, 2011 is National Household Survey data rather than the census). In practice, because of the data source, what the study is actually looking for is something closer to transition rates: it’s only looking at 17-18 year olds in most provinces (18-19 in Ontario for the years before the final year of high school was eliminated), and more importantly it’s only looking at those students who are declared as resident in a household with their parents. There are a lot of fairly noisy line graphs and tables in this section and a number of conclusions, but I think the important ones are 1) participation rates rise with family income and parental education (no kidding); 2) over those 20 years, PSE participation rates of 18 year-olds rose in some parts of the country (Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland) and fell in others (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Nova Scotia); 3) individuals with at least one immigrant parent are much more likely to attend PSE and specifically university and 4) Ontario is the only province to see improvements in access to both universities and colleges among below-median income students over this period.

Now, where things get a little fraught is the policy conclusion piece. It states – correctly – that most changes in policy appear to be uncorrelated to changes in outcomes. It also states that the one place and time where we see major increases in access is in Ontario around the time that the McGuinty government introduced the “30% off” tuition benefit. The authors do not outright state a causal relation between the two events, but there is no attempt to seek other possible explanations for the change, either. Nor, unfortunately, do they try to do much in terms of trying to tie policy changes to actual changes in net costs, the way Wilfrid Laurier’s David Johnson did in his 2008 piece “How is Variation in Tuition across Canadian Provinces Related to University Participation in the Youth in Transition Survey”, or as we at HESA did in The Many Prices of Knowledge or Beyond the Sticker Shock: A look at Canadian Tuition Fees (back when we were still EPI Canada). This means that they aren’t looking at real net price changes, but just working from announced policy changes. (The significant increase in the percentage of students with at least one immigrant parent – particularly in the Greater Toronto Area – was probably worth exploring as a factor in Ontario’s rise in over the past decade).

I don’t mean to knock the piece as a whole, because it’s methodologically sound (and the authors do put a lot of effort into the caveats about what the data does and does not show) and brings a lot of valuable information to the table. And it’s not implausible that a one-off 30% decrease in net tuition might have had a significant enrolment impact on 18 year-olds, although it does beg the question why a roughly-similar sized reduction in Newfoundland a decade earlier did not have a similar effect. But I think the way the conclusion is phrased is probably more suggestive than the evidence warrants.

That aside: it’s another great piece of work from SRDC and another useful public service from HEQCO to have commissioned and published it. Kudos.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Why more PSE participation in ON than NL with similar tuition reduction policies? Possible factors: 1) more opportunity for young NLers in high-paying offshore oil or AB tar sands jobs, 2) only 1 uni & 1 college in NL, high cost of leaving to attend PSE.