You may have seen the news from California regarding a lawsuit by a well-to-do Berkeley resident against the University of California which has forced the latter to reduce its 2022 enrolment by 2,600 students. Basically, the plaintiff – a well-to-do local who spends half his time in Nelson, New Zealand – said that too many students were destroying the neighbourhood and sued the university over its enrolment plans, using the California Environmental Quality Act. A lower court agreed with the plaintiff and issued an injunction against the university that was upheld by the California Supreme Court; however, the state legislature eventually came to the University’s rescue and passed legislation nullifying the Court order. Access protected; crisis averted.

So look, obviously, this is a perfect example of obstructive NIMBYism, and the way that regulations made for the 1970s are halting our ability to densify urban neighbourhoods in response to the challenge of climate change. But on the other hand: dude’s got a point. Growing enrolments – and specifically, growing numbers of international students who need short-term housing – are putting real pressure on rental markets around the world, and have been for some years. You name it: Auckland, London, Dublin, Amsterdam – it’s not hard to find stories of cities where surging numbers of international students are putting enormous pressures on short-term housing markets.

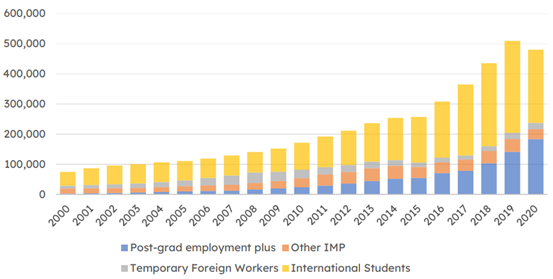

It’s happening in Canada too. It’s just that, in that typical Canadian way, we don’t want to talk about it. And yet the evidence is absolutely incontrovertible: just read these two recent pieces (Forecast for Failure and One Million New Ontarians) from the Institute for Smart Prosperity to get a sense of how international students are straining the housing market. Check out the figure below, which is taken from the latter report; it shows the number of non-permanent residents in Ontario by visa type. International students jump from about 100,000 in 2011 to about three times that many in 2019.

Figure 1: Non-Permanent Residents in Ontario, by Classification Type and Year, 2000-2020

Where exactly do people think all these students are living? Are we under the impression that an equivalent number of new rental units have appeared in Ontario during this period? Because I can assure you that they haven’t. As basic economics would suggest, the result is that rents – and also land values – are dealing with increased scarcity.

Let me spell this out a little bit more. Sine 2010, Canadian governments have, on aggregate, held institutional funding to universities and colleges to inflation. Institutions, for various reasons, have decided that they cannot subsist on just inflation. As a result, they have turned to the one market that can really make up for stagnant funding: international students. Getting foreigners to pick up the tab for our own institutions sounds like not just a public good but a public great, but there is a catch. These international students need a place to live. And in the absence of anyone actually choosing to build purpose-built housing for these students (because that would cost too much and would kill the entire purpose of admitting international students in the first place), institutions have simply imposed an externality on their surrounding communities: higher rental rates for local residents. Or rather: higher shelter costs for younger/poorer local residents and big capital gains for landowners.

Now, you can choose to blame universities for these externalities (for being unable to keep their expenditures in line with inflation), or you can choose to blame provincial governments (for being unwilling to increase funding in a way that would satisfy institutions), but either way this situation is doubleplusungood. And it’s definitely not in keeping with the claims universities make to the communities to which they belong about being engines of wealth and prosperity.

The main culprit here are restrictive urban planning laws which make it difficult to densify housing. But I don’t think it makes sense to let institutions off the hook entirely. Institutions all have a pretty good idea of the extent to which the growth in their international student numbers are outstripping growth local rental capacity: the number who are actually doing very much in terms of actively building new housing to bridge this gap is pretty small. More common is a sort of shrug – well, housing is expensive, and if we had that kind of money, we wouldn’t need so many international students, so…

If institutions genuinely want to contribute to inclusive growth in their communities, they have to be a lot more pro-active in developing new housing. That could mean joining forces with pro-growth forces in cities to make it easier to densify: but it also means putting money into housing. Buy land, build houses, run student housing. Enter into PPP arrangements? Sure, within reason that can help expand supply. But the main things is: build, build, build. Governments can help too: CMHC already has some forms of loan insurance for the construction of student housing, but it could go further and return to its policies of the 1960s where it provided loans directly to universities on 50-year amortizations and interest rates equal to the government’s rate of borrowing (currently, that’s about prime minus 120 basis point). Or, we could copy the State of California, which last year devoted a half-billion dollars in one-time funding to increase affordable housing near campuses, and which is considering adding another $5 billion into the project in the near future.

Success will require a lot of co-operation and co-ordination between institutions and different levels of government, which, as we all know, is not necessarily a strong point of the Canadian post-secondary sector. But it’s both urgent and necessary. Low-income urban Canadians simply can’t be the ones who indirectly have to pay for expanding university and college budgets.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Now, try doubling a university’s enrollment in a small city, like say, Sydney, NS, where housing was not plentiful before the doubling occurred. Also, do that without the university having any idea how many students were planning to show up, nor giving the community a heads-up that they were coming. We had international students who had come from halfway around the world living in hotels and walking door-to-door in residential areas looking for places to live….Not a good welcome, but the upper admin did give itself a good pat on the back with all the funds it was raking in.

Also, the local Cineplex is now doubling as classroom space with the university using theatres as lecture halls for its make-money programs (cbu.ca/cineplex).

Growth is good, but growth without proper planning is not.

With regards to UC Berkeley, in their defense, they have been trying to build additional student housing, and they have the land to be able do so, but their plans keep on being blocked by the same group that took them to court over their enrolment numbers. It’s not that the Save Berkeley Neighborhoods group feels that more students are putting pressure on rent (they don’t care about that they all own their own homes), they don’t want increased density, at all. They want to maintain the character of their existing neighbourhoods replete with single family homes, and profit from the growth in value that they have experienced due to constrained supply. It’s all about NIMBYism.