Last month, my colleague Andrew Parkin at the Environics Institute published a fascinating little piece entitled Is Post-secondary Education is a Waste of Time?, which looks at Canadians’ evolving views on the worth of higher education (Andrew is a former Director General of the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, so we can safely infer that this is not an expression of his own feelings)

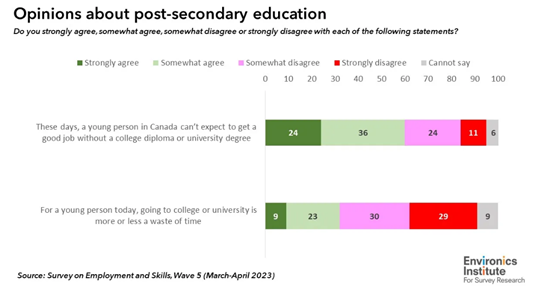

Environics asked two questions: “these days, a young person in Canada can’t expect to get a good job without a college diploma or university degree.” And “for a young person today, going to college or university is more or less a waste of time.” The responses are summarized here in a graphic:

Now you might expect that the way people answer these questions is symmetrical: those who think young people can’t get ahead without degrees are the same people who say a degree is not a waste of time and vice-versa. But here’s where things get interesting. There are, in fact a substantial number of people whose views are – superficially, anyway – inconsistent. In total, 20 percent of the population –believe both that postsecondary attendance is both necessary to get a good job AND a waste of time. Those figures are higher for those identifying as Black (26%), those who are currently students (28%), those between 18-24 (31%) and among males 18-24 (36%).

Now that’s a pretty interesting result, one that should make anyone interested in access to education go “hmmm”. Parkin posits that what is going on here is annoyance at credentialism: people think that post-secondary diplomas and degrees are necessary because employers require applicants to have a diploma or degree, but not because of what you actually learn. That’s a reasonable inference, but I think there are a bunch of other possibilities which are worth considering. Let me give you four.

The first most important possibility is a slight re-statement of Andrew’s hypothesis. It’s not quite that people think the degree as a whole is “a waste of time”, but rather that degrees/diplomas take too much time; that is, a lot of people think they simply take too long relative to the benefit they confer. Maybe they want shorter credential lengths. Maybe they think degrees contain too much filler and not enough meat, or maybe they think there should be more competency tests or prior learning assessment to speed through the process. Worth asking people, especially those who actually are students or young people.

The second has to do with the gender gap – implicitly ten points higher among men 18-24 than women of the same age. I think this stems from something different. For years, scholars who look at finance and risk have noted that men and women have different patterns of investment: specifically, when it comes to investing, women are significantly more risk-averse than men. If, overall, people think that education is a “safe” investment, then we should hardly be surprised that men would be more likely to prefer a riskier alternative – that they can “make it” without a guaranteed ticket to a “good job”.

The third has to do with how people interpret the term “waste of time”. I think it’s quite possible that some of them mean “waste of money” (and since, as the adage goes, time = money, this is consistent). It would be interesting to examine the data to see whether local tuition fee levels make any difference here. More simply: how does this data look in Quebec compared to the rest of the country? The answer might be revealing.

But there’s another more complicated possibility. About twenty years ago, when I was working at the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, we did some public polling (details of which were later published here) which revealed some very interesting facts about how people saw higher education as an investment. There were two key findings. First, people generally overestimate tuition costs and underestimate the gap in wages between people with degrees and those without. And second, the degree to which people’s estimates were accurate were inversely related to family income. That is, lower-income families were systematically over-estimating tuition and underestimating the benefits.

I can easily see how this phenomenon would change people’s responses to the kind of questions Environics posed. Again, if the concepts of “money” for “time” are, to some extent, being conflated by respondents, and some people are both overestimating costs and underestimating benefits (specifically, the gap between earnings in a “good job” and a not-so-good one), then that would certainly account for some of what we are seeing here. In particular, since Black people have among the lowest average earnings of any ethnic group in Canada, this might also explain why this group in particular shows the paradoxical result that it does in the Environics data.

Anyways, this is all speculation. Someone (ESDC? CMEC?) should pay Environics to do some more analysis on their current data, asking questions about the relationship with household income and/or occupation (or, in the case of younger people, parental income/occupation). More expansively, they could pay for some extra questions on the next round asking some follow-up questions that clarify the time/money issue and, to the extent that it really is about time, figure out what people – students especially – think about why degrees/diplomas take too much time and how they think it could be shortened.

Asking these questions will help governments demonstrate their commitment to access to education.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Agreed that students and families are often mistaken about the costs of university attendance and the returns from it because of assumptions they make about what employers want. Is it entirely their mistake and the mistake of colleges and universities in designing programs and recruiting students to them? There is an obverse. Are employers mistaken about what skills and curricular preparation their jobs require? We should remember Ivar Berg’s The Great Training Robbery (1970, 2003) and Michael Spence’s Nobel Prize lecture on asymmetrical markets (2002). Both present convincing evidence that employers over-pay or under-pay graduates because of their own lack of reliable information about the jobs that they will fill. In other words, they are by themselves under-informed and perhaps mis-informed by the higher education establishment and “creeping credentialism” about the productivity of graduates. What, then, looks like “waste” to some students maybe a lucky windfall to others. Final note: Spence gave two examples of highly asymmetrical markets. One, not surprising today, was real estate. The other, which would not have been a surprise to Berg, was higher education.

I’m more interested in the other end of your (or rather, Mr. Parkins’s) graph: who are the people who think that a university education is unnecessary in the job market, but still not a waste of time?

They’re our key market. Certainly, they’re the students I want in my classes.