My work exists at the junction of a few different fields – management, public administration, sociology and economics (which is kind of funny because my degree is in none of those things) – all of which have their own specialized jargon. One of more jargon-y terms that I know I use a lot is “human capital”, a term which often seems to be misconstrued. So, I thought I would give an explanation a shot.

The OECD definition of human capital, which is as good as any, is “the knowledge, skills, competencies and other attributes embodied in individuals or groups of individuals acquired during their life and used to produce goods, services or ideas in market circumstances”. The term “capital” here can be distracting – former World Bank chief economist Branko Milanovic, drawing on Thomas Piketty. has suggested the term human capital “obfuscates the crucial difference between labour and capital by terminologically conflating the two.” This is unhelpful because such “capital” can really only de deployed/realized in the form of “labour” whereas financial capital does not require labour to be realized. So why use the term, when a simpler one like “skills” was available? Mainly because the coiners of the term wanted to emphasize i) skills are a stock not a flow and ii) the investment angle, that people invest time/money in developing skills. You can come down on different sides of the issue (Gary Becker, who developed the term, has a point since the Nobel committee did award a prize to him for this stuff, and Carleton’s Nick Rowe has an interesting rebuttal to Milanovic here), but it’s possible to use many of human capital theory’s insights about decisions to take/not take more education (that is, the aspects which deal directly with issue of access) without getting too caught up in these discussions.

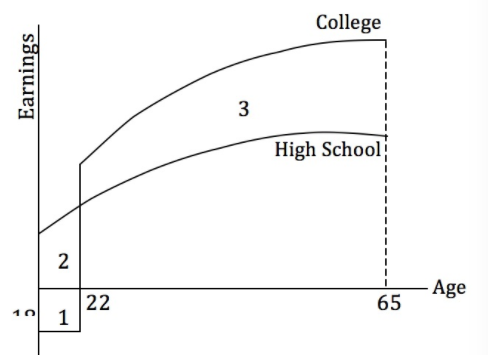

The basics of the investment decisions are encapsulated below in figure 1.

Figure 1: Human Capital Theory

So the x-axis is time/age, and the y-axis is earnings. This graph depicts the go/no-go decision regarding post-secondary decision for a typical 18 year old. The lower of the two curves represents a lifetime income path for someone with high school education, while the upper curves describes it for someone with a bachelor’s degree. Area 3 is therefore the notional “benefit” of higher education. But there are costs, namely, the income foregone from time spent studying (area 2) and the actual fees paid to attend the institution (area 1). If area 3 is larger than areas 1+2 (all figures suitably adjusted into net present values) then the education is “worth it” and a student should make the investment; if not, not.

When you think about access this way, a whole bunch of things come into focus. Such as:

- Appropriate fee policy is contingent both on length of degree and graduate earnings premiums. The shorter the program, the more earning years a person will have and hence the greater the total benefit. All things being equal, shorter programs delivering the same credential should be charging more. Similarly, the level of fees should be related to the graduate earnings premium. If earnings do not increase much in line with education (the case in parts of Scandinavia, for instance) then the case for fees is much weaker; the case for fees rising in line with anticipated graduate earnings by field of study is pretty good.

- From an investment perspective, foregone income and tuition fees are the same thing. Therefore, an increase in minimum wages should have an identical impact to an increase in tuition fees as it raises the cost of education.

There are a lot of valid objections to this theory, of course. Teenagers don’t calculate costs and benefits out to the dime before making a decision. The benefits to education are not purely monetary. The costs of education are not purely monetary either, particularly if you come a low-education background/community and there is a significant process of cultural adaption that needs to occur in order to succeed at school (which certainly has psychological costs).

But these objections only matter if you take the theory literally rather than seriously. Of course, teenagers aren’t amateur econometricians, but this is still a schematic of the cost/benefit decision most people implicitly use. Of course, not all costs and benefits are monetary, but they are costs and benefits nonetheless and they can still be put on both sides of the ledger when weighing the question “is getting this degree worth it”? And liquidity still matters: just because something is a good investment doesn’t mean everyone has the scratch to put themselves through school once they’ve made the decision to go. This is why student loans are such an important policy tool.

Long story short: human capital theory is a good metaphor. Use it responsibly and it’s an important tool to think about access and related policy matters.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post