Yesterday, I showed how universities in New Brunswick were – despite welcome new promises of stable funding from the provincial government – facing problems because salary increases were going to eat all the available new money. Some of you possibly thought I was being alarmist. But it’s easy enough to show how this can happen. In Ontario, it already has.

For data here, I pulled the financial statements for the last five years at the “Big 8” (Toronto, Waterloo, Western, Queens, Guelph, York, Ottawa, and McMaster), which comprise about 75% of all university spending, and hence are a pretty good proxy for the university system as a whole. It’s not as good as Stastcan data; but, on the other hand, it gives me something past 2011, which is the most recently-available Statistics Canada/CAUBO report. And here is what it shows:

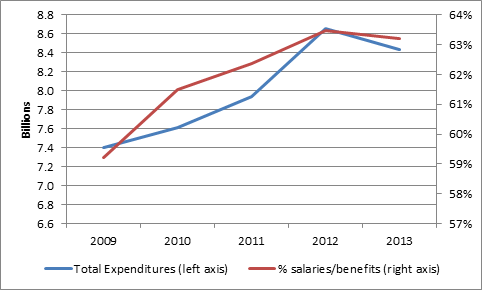

Figure 1: Total and Salaries/Benefits Expenditures, 8 Largest Ontario Universities, 2009-2013

Expenditures at these institutions rose from $7.4 billion in 2009 to $8.6 billion in 2012, before falling back to $8.45 billion in 2013. That’s a 14% nominal increase, which is about 6% after inflation – not bad. Meanwhile, salaries and benefits rose from being 59% of overall budgets to being 63% of overall budgets.

Now that doesn’t sound so bad, either. But let’s look at the same data another way:

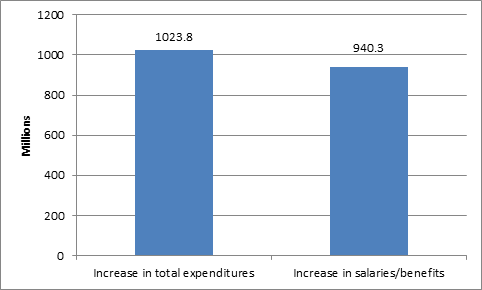

Figure 2: Increases in Total and Salaries/Benefits Expenditures, 8 Largest Ontario Universities, 2009-2013

This looks considerably less good, doesn’t it? As new money has come in and permitted higher spending, salaries and benefits have eaten fully 92% of the increase. This, friends, is the consequence of increasing salary mass by 5% per year, when income is only growing at 3%.

And the consequences for the rest of the budget? After salary increases, the Ontario 8 only had $83 million to put into non-salary areas. On a base of about $3 billion, that’s an increase of about 3%, but after inflation, that’s actually a 4% reduction, i.e., a fall of about 1% per year. And of course much of that money is earmarked for things like research, so in terms of disposable income, it’s likely that the figure is actually much higher.

Outside Ontario, we don’t see quite the same pattern. I pulled 7 other comparable institutions (UBC, Alberta, Calgary, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, McGill, and Dalhousie) and found that on the whole they spent a greater proportion of their money on salaries (66% in 2013, compared to 63% in Ontario), but that there was no sudden change in the way money was spent (only 67% of new expenditure went to salaries, meaning the average went unchanged). That said, there were differences inside this group. Most actually managed to decrease their salary-to-total expenditure ratios; the two exceptions were Alberta (where salaries took 86% of all new expenditure) and McGill (where they took an astounding 179% of new expenditures).

For a set of institutions that endlessly bang-on about how hi-tech they are, Ontario universities are apparently one of the very few industries in the provinces that are becoming more labour intensive over time. And that won’t change until compensation increases start coming into line with increases in income.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

On first reading this sounds like a reasonable argument. But, where is the data on enrolment? Would the data show more or less HR productivity when student numbers are factored in?

It would be interesting to see the composition of these salary increases. I beleive that the student/professor ratios at Ontario universities (and others) have increased lately and have been doing so for some time. If so, and by this measure, productivity has increased (although I won’t comment on the qualitative changes in degrees). I suspect that these figures cloud the increase in hiring (and perhaps salaries) of non-teaching staff at univerisities. Hopefully this will be the topic of an upcoming OTTSYD.

All in good time, my friend. Academic vs. non-academic salaries is tomorrow. Student:faculty ratios are next week.

Excellent! Will look forward (as always) to reading what you have to say. Stay warm!

Thanks for highlighting these issues, Alex. Re your conclusion that things “won’t change until compensation increases start coming into line with increases in income”…might be worth noting that there are two ways this can happen.

Individual compensation could come more into line with increases in revenue, although the former is driven partly by the demographics of the workforce and ‘progression-through-the-ranks’ policy while the latter is not.

Or, individual productivity could increase. Many institutions have had a go at this by increasing class sizes, but there are better ways to do this – better both financially and pedagogically. David Trick and I did some work on this for HEQCO last year, and the conversation is continuing at http://www.tonybates.ca/2013/12/23/productivity-and-online-learning-redux/.