Yesterday, I talked a little bit about how Canada needs better data to improve understanding of what various types of intervention – like Alberta’s tuition freeze or Targeted Free Tuition in Ontario and New Brunswick –do in terms of access. But data is not enough: it’s a necessary condition, but not a sufficient one. An example from our friends down in New Zealand can perhaps show why.

We are coming up on the first anniversary of the implementation of free first-year fees at New Zealand universities and colleges, and so naturally people want to litigate about what happened, is it working, etc. Generally, New Zealand has *excellent* data on post-secondary education. Nevertheless, its current debate on “did free first-year work” is a bit disastrous, mainly because people there can’t seem to agree on the terms of the debate.

Do take a minute to digest this article about the current bunfight. As precisely as I can lay it out, here’s what the two sides are saying:

Pro-free-fees. The program is working. 40,000 students received a subsidy. 31,600 fewer students had to borrow to pay their fees and total borrowing fell.

Anti-free-fees. There are fewer students in tertiary education and training than there were last year. Maori students aren’t getting their share of the money and enrollments at the three Wānanga are down, so obviously the policy is a failure for Indigenous students (a New Zealand reader has informed me I’m not supposed to use English plurals on Maori words, so it’s one Wānanga, many Wānanga, etc).

Where to begin?

The issue about whether there are more or fewer students that the previous year is an empirical one, and as the article points out it gets a little muddier depending on how you cut the data. As I understand the data, it seems to suggest that most of the decrease has come on the short-term training side, and that while there might be some shifting between universities and polytechnics, it’s kind of a wash on the public education side.

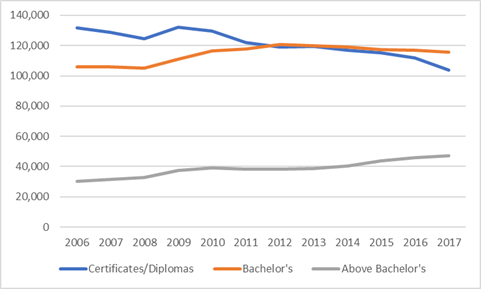

But there are two larger points one should probably use before pointing to stable enrolment figures to declare success or failure after a single year. The first is: do you really think a policy announced in November is likely to have had a rally big impact on enrolments when the standard application closing date in New Zealand is December 1? The second is: wouldn’t it be a good idea to look at demographics before getting overly excited? Because I look at the long-term data and see that slight declines in enrolment (below the graduate level anyway) have been the norm for over a decade.

Figure 1: Tertiary Enrolment by Level, New Zealand, 2006-2017

As for the argument that the policy is a failure because Maori students don’t get their fair share…that’s an interesting one. We could use it here in Canada, too. Indigenous youth in Canada would get nothing like their fair share of money for free tuition because they are under-represented to begin with. (I urge everyone, next time they are in the presence of someone arguing in favour of free tuition, to ask them why they support an anti-indigenous policy, just to see what happens).

All that said, if the anti-free-fee arguments are poor, the pro-free-fee arguments are worse. Basically, they amount to: “of course the program is a success! We transferred money to students! What more do you want?” If this impresses you as an argument, you probably shouldn’t be reading my blog.

There are three problems here. First, to have a debate, you need to have a definition of what success would look like. It’s legitimate for the two sides to have different definitions, but you must state them upfront. If the argument is “free fees will increase student numbers, period”, then that’s the correct measure, not whether or not a particular group gets its “share.” (In fact, increased numbers are quite unlikely to result from this program because the government has not increased institutional funding to accommodate increased demand. Rather, the government’s pre-election rhetoric was about how better finances would “relieve student stress” and thus lead to better academic results and lower drop-out rates, two results which are empirically testable but which have not yet been tested).

Second, you need to have some context, especially around demand and demography. Without it, you look dumb.

Third, you need patience. The impacts of new policies are never immediate. In the case of something like access to postsecondary education, where we know that attitudes are mostly set by early secondary school, it’s possible one wouldn’t see results for 3-4 years. Plus, you must collect and analyze data. Plus, you have to put it into context.

Policy analysis – good policy analysis anyway – isn’t a short process. It needs good data (better than we tend to produce in Canada), but it also needs definitions of success, context and patience. We should strive for all three.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post