Academic bureaucracy is weird. Basically, about 150 years ago, it was decided that it was important to have two layers of administration interposed between an individual faculty member and a University President (and later, once the university expanded, a senior team with various Vice-Presidents). One layer came to be called a “department” and one level came to be called a “faculty”. These theoretically mapped on to the branches and limbs of the Tree of Knowledge (so to speak). But they never seemed to map consistently: just in the Golden Horseshoe you have universities which where Arts and Sciences is one enormous faculty, universities where Sciences, Social Sciences, Humanities are split into three different faculties, and places where Arts are jammed in with various types of professional studies. At different universities, Health can be found anywhere between one and five faculties. And then there is the vexed question of where “schools” fit in. Schools are often areas of professional practice that in reality are disciplinary-like in breadth, but are professionally-oriented in such a way that they have no wish to be bundled with anyone else (often the case in Social Work). They tend to get treated like faculties, and their leaders given the term “Dean”, even though they often aren’t multidisciplinary.

Depending on how you cluster this stuff, you get very different-looking universities. Among the U-15 institutions, most universities have between 12 and 16 faculties. But some fall well outside this range: at one extreme you have McMaster, which has managed to keep their universities to just six Faculties apiece, whereas the University of Manitoba has twelve Faculties, four schools and five health “colleges” (each of which has its own Dean, but if I understand correctly all seem to report to another Dean, who also doubles as a VP Health Sciences).

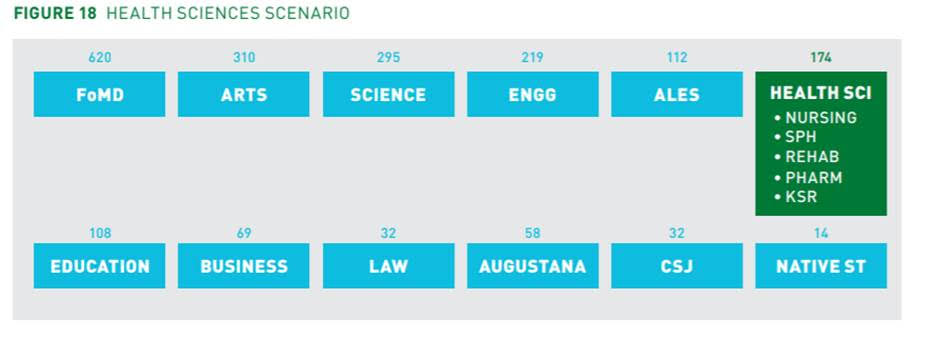

All of which brings me to the University of Alberta, where the new President, Bill Flanagan, seems to have decided that this university’s 18 faculties are too many and need to be cut down. This is part of a larger “re-structuring” meant to deal with the significant budget cuts made by the provincial government over the past eighteen months. According to the Academic Restructuring Working Group’s Interim Report (from which I have lifted the nifty visuals below), they are pondering three models. The first of these, called the “Health Sciences Scenario” merges all the smaller Health Sciences disciplines into a single entity, thereby reducing the number of faculties by four.

(the numbers above each of the faculty boxes on the chart are, if I understand correctly, the number of permanent FT faculty)

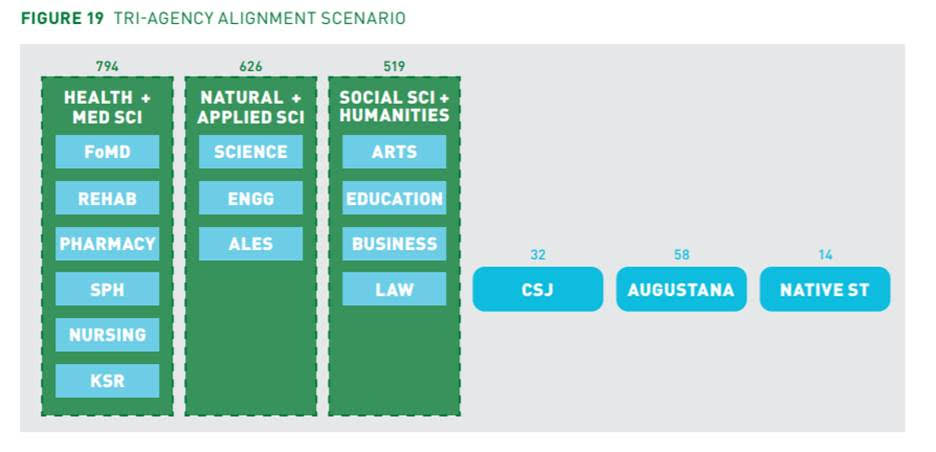

The second scenario, which is transparently the one senior administration favours, is called the Tri-Agency Alignment Scenario. Here, nearly all faculties would all be merged into one of three “divisions”, based on the granting council to which they primarily relate (the Native Studies faculty as well as the Augustana and St. Jean Campuses stay outside this system).

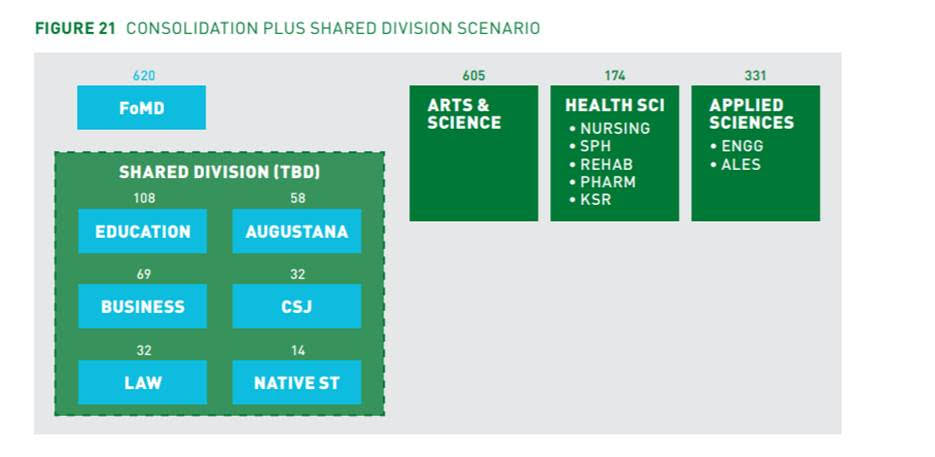

And then just to round things off, there is a weird compromise version in which Arts & Science gets their own “division”, the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry gets to tell everyone else to do one, and Augustana, St. Jean and Native Studies get lumped in with Education, Business and Law because reasons.

Now, you ask – what does all this have to do with budget cutting? Well, this is where it gets tricky. The budget rationale is basically that because faculties are innately voracious and jealous, they tend to duplicate functions. And moreover – this is the interesting part – precisely because they duplicate functions in spite of their smallish sizes, a lot of people within each faculty do more than one job, with many of them being “off the side of the desk”, so to speak, meaning there are a lot of “generalists” in these positions. The theory is if you started stacking faculties together you could hire specialists to do each job properly and thus provide equivalent services with fewer staff. This might be true, and the University says it has an internal analysis that proves this, though the data has not been released. What has been released is an interesting deck showing how some top universities around the world have restructured and reduced faculty numbers and everything has turned out swimmingly, which is intriguing but not especially persuasive.

(There is an argument that these divisions might be able to power curricular innovation, by encouraging more programming across faculties within a single division. I wouldn’t dismiss these arguments entirely, but I would note that under the favoured model, Arts, Business and Health are all kept apart from core STEM, meaning that some of the most important potential innovations are no more likely under the new system than the old one).

It’s worth remembering that at the end of the day, no matter how you choose to group academic programs together, you’re still teaching roughly the same number of students with roughly the same number of academic staff in essentially an un-reconfigured set of programs, so direct program costs don’t change a whole lot. What this strategy is aiming for is to reduce – perhaps significantly – the “back-office” costs behind each of these programs. Processes like HR, budgeting, IT, student support, etc., which were done at a faculty level are going to get booted up to a higher “division” level. Of these, the one that will get professors’ antennae up is budgeting, especially when it comes to things like tenure lines. Because now Astrophysics isn’t just fighting against Palaeontology and Chemistry for money, it’s also up against departments in Engineering and Agriculture/Life Science. With budgets shrinking, it’s easy to see how this might lead to conflict.

It should be said that you don’t need to re-organize academically to achieve these kinds of savings. The University of Manitoba did this through something called the Resource Optimization and Service Enhancement (ROSE) program, which I gather was reasonably effective, if not overly popular. Would this be a better solution for U of A? Hard to tell without more data, and ROSE was a slow process.

To return to the original question about the “right” number of faculties: the correct answer is “as few as you can get away with” (which is also the answer for the number of departments, by the way). Any new nodes on the academic bureaucracy add costs. Not overwhelming ones, because program costs are the big cost driver: running twenty programs through one faculty is not much more efficient than running them through two. But when your institutional budget is over a billion dollars, those little savings add up and are worth pursuing.

So bravo to University of Alberta for at least choosing to explore some interesting if controversial new ideas. We’ll see how they turn out.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I think you’re missing the question of how disciplines represent ways of seeing the world. Different faculties can be seen as collections of allied disciplines. If the question of administration were the only one, we could simply divide disciplines at random into numerically equal units, then assign them letters or some other arbitrary signifier. Think of how soldiers are assigned to numbered units in large armies, all of them symmetrical.

Gathering disciplines into faculties is a matter of deciding who will encounter each other at faculty meetings and in faculty committees, what sorts of scholars are likely to get along with each other, and what sort of intellectual community they will therefore form. In reality, the situation is more like that of the Canadian army, with its historical and named regiments, and esprit de corps. I don’t know about all your readers, but I’ve certainly seen departments and faculties which simply failed to form intellectual communities, others in which the intellectual communities seemed frankly inbred, and yet others whose members fled to institutes or residential colleges.

That’s good