Last month, the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO) published a paper entitled “Redefining Access to Postsecondary Education”. It raises a number of interesting questions about access in Ontario (which apply to Canada generally), so it’s worth examination.

Stripped to the basics, the document lays out the following point (quoted from the Executive summary) that Ontario funding and student aid policies “have resulted in a dramatic increase in overall enrolment at Ontario’s colleges and universities over the last two decades. Ontario is now a world leader in adult postsecondary attainment. The assumption inherent in these policies was that growth would also improve the equity of access. However, the evidence suggests that it has done little to achieve equitable access for those students who have been traditionally excluded from postsecondary and labour market opportunities.”

So, let’s stop there for a moment because I think the authors are choosing their words very carefully and correctly, but it is liable to misinterpretation. The evidence is not that traditionally-excluded groups have seen no gains in access. The evidence is that the increase in participation has been spread quite widely and that therefore the gaps in access appear to have remained relatively constant (though the authors also note that the data on this point is not all it might be, so we may not have the entire picture). Whether you consider this a failure or not is presumably a matter of perspective. Have access opportunities increased? Yes. Have relative opportunities increased? No. Half-full? Half empty? You pick.

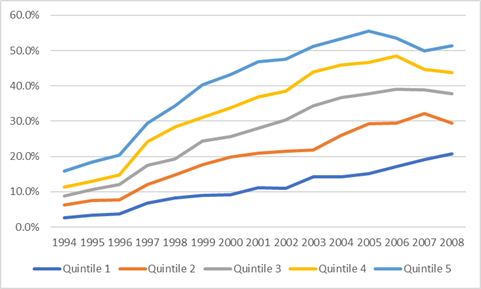

The authors themselves don’t point to any international evidence, but I

feel compelled as a ‘comparativist’ to point out that this experience is hardly

unique to Canada. Right across Europe, massification has had similar

effects. Figure 1 shows what happened in Poland to enrolments by income

quintile over a 14-year period where enrolment nearly tripled, in part through

the introduction of private universities and the partial introduction of

tuition fees at public universities.

Figure 1: Access to Higher Education in Poland by Income Quintile, 1994-2008

Source: Herbst and Rok (2010) The Equity of the Higher Education System: Case-Study Poland. Available at: http://www.euroreg.uw.edu.pl/en/publications,the-equity-of-the-higher-education-system-case-study-poland

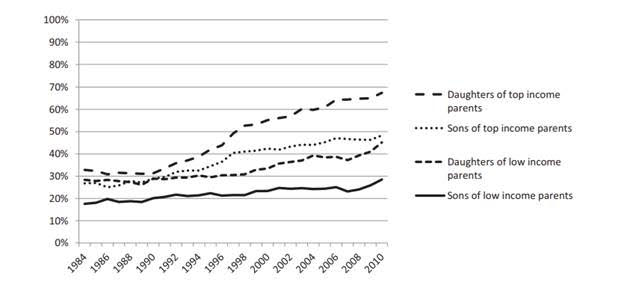

Figure 2 shows HE attendance by gender and income group in notably free tuition Denmark over a 25-year a period in which overall enrolment in universities quadrupled:

Figure 2: Predicted HE Attendance in Denmark by Gender and Income Background, 1984-2010

Source: Jens Peter Thompson, Maintaining Inequality Effectively? Access to Higher Education Programmes in a Universalist Welfare State in Periods of Educational Expansion 1984–2010, in European Sociological Review, vol 31 no 6 (2015).

I could go on here, but you get the idea; growing participation rates and constant (or even growing) inequality rates aren’t something specifically Canadian. In fact, they are almost universal. There is even a theory to describe this: “Effectively Maintained Inequality” (EMI). Developed by the American sociologist Samuel Lucas, it “posits that socioeconomically advantaged actors secure for themselves and their children some degree of advantage wherever advantages are commonly possible.” If the socioeconomically advantaged can obtain an advantage by obtaining a new higher level of certification (e.g. secondary school completion in the post-war period, bachelor’s degrees in the late 20th century), they will do so. If this is not possible, then the socioeconomically advantaged will obtain qualitative advantages/distinctions; that is to say, as a level of education becomes universal, then other things will start to confer distinction such as which institution one attends, which disciplines one studies (a proposition for which there is a wealth of data from a number of countries: I recommend Yossi Shavit et al’s Stratification in Higher Education: A Comparative Study if you want to know more about it)

None of this is to argue with the point the authors are making; it is however to suggest that the phenomenon that they are highlighting isn’t one anyone else seems to have “solved”. Social stratification is universal, and so is its reproduction via education. It is something to work on, obviously – limiting inherited privilege should everywhere and always be job 1 – but perhaps with due humility as to the potential for success.

If there is one place where I might differ a bit from the authors, it is with the following statement: “The analysis presented in this paper suggests that it is time to declare victory on growth and focus more intently on ensuring that all Ontarians have an equal opportunity to access and succeed in Ontario’s postsecondary system.”

Possibly, this is just a rhetorical flourish, but I really hope no one takes that passage literally. If you “declare victory on growth”, it’s hard to see how we can be successful in opening up opportunity to underserved student populations, because such absent system growth, such opportunity can only occur by taking spots away from social groups who already have them. And if there is one rock-solid lesson EMI teaches us, it is that the middle-classes’ privileges with respect to getting their kids into higher education will only be relinquished if you pry them from their cold, dead hands. Improved access for underserved groups, like it or not, almost certainly means continued system growth.

Still, a minor point. I look forward to seeing where HEQCO takes this new line of research.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post