Earlier this week, I gave a speech in Shanghai on whether countries are choosing to focus higher education spending on top institutions as a response to the scarcity of funds since the start of the global financial crisis. I thought some of you might be interested in this, so over the next two days I’ll be sharing some of the data from that presentation. The story I want to tell today is about how exceptional the Canadian story has been among the top countries in higher education.

(A brief aside before I get started on this: there is nothing like a quick attempt to find financial information on universities in other countries to put our own gripes – Ok, my gripes – about institutional transparency into some perspective. Seriously, you could fill the Louvre with what French universities don’t publish about their own activities.)

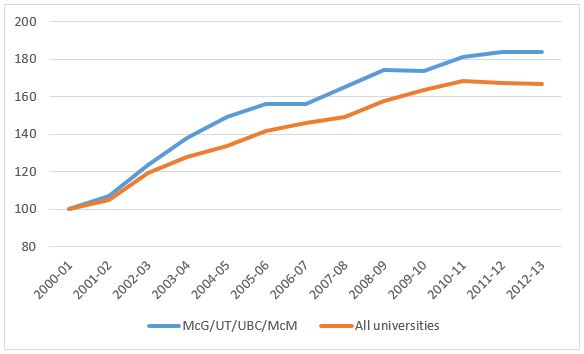

For the purpose of this exercise, I compare what is happening to universities generally in a country, to what is happening at its “top” universities. To keep things simple, I define as a “top” university any university that makes the Top 100 of the Shanghai Academic Ranking of World-class Universities (ARWU). In Canada, that means UBC, Toronto, McGill, and McMaster (yes, it’s an arbitrary criteria, but it happens to work internationally). I use expenditures rather than income because fluctuations in endowment income make income numbers too noisy. Figure 1 shows the evolution of funding at Canadian universities in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) dollars.

Figure 1: Real Change in Expenditures, Canadian Universities 2000-01 to 2012-13, Indexed to 2000-01 (Source: Statistics Canada/CAUBO Financial Information of Universities and Colleges Survey)

So this is actually a big deal. On aggregate, Canadian universities saw their expenditures grow by nearly 70% in real dollars between 2000 and 2010. For “top” universities, the figure was a little over 80% (the gap, for the most part, is explained by more research dollars). Very few countries in the developed world saw this kind of growth. It’s really quite extraordinary.

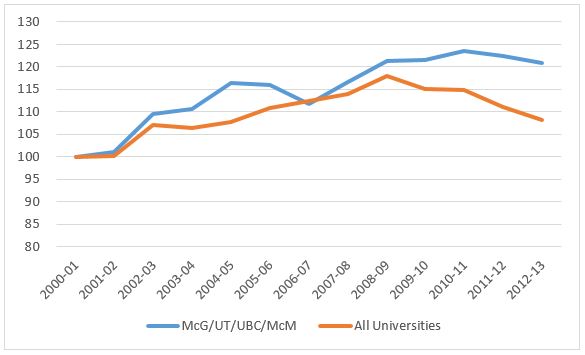

But a lot of that money went not to “improvement”, per se, but rather to expanding access. Here are the same figures, adjusted for growth in student numbers.

Figure 2: Real Change in Per-Student Expenditures, Canadian Universities 2000-01 to 2012-13, Indexed to 2000-01

Once you account for the big increase in student numbers, the picture looks a little bit different. At the “top” universities, real per-student income is up 20% since 2000, but about even since the start of the financial crisis; universities as a whole are up about 8% since 2000, but down by nearly 10% since the start of the financial crisis.

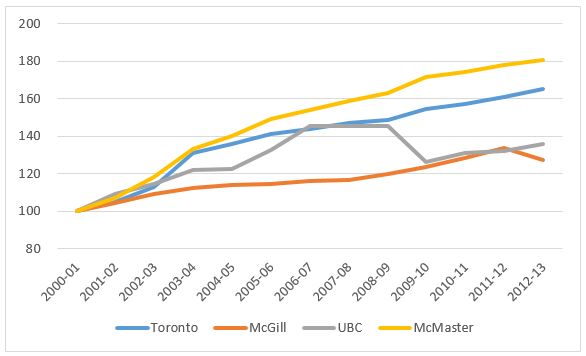

This tells us a couple of things. First, Canadians have put a ton of money, both collectively and as individuals, into higher education over the past 15 years. Anyone who says we under-invest in higher education deserves hours of ridicule. But second, it’s also indicative of just how much Canadian universities – including the big prestigious ones – have grown over the past decade. Figure 3 provides a quick look at changes in total enrolment at those top universities.

Figure 3: Changes in enrolments at highly-ranked Canadian universities, 2000-2001 to 2012-13, indexed to 2000-2001

In China, the top 40 or so universities were told not to grow during the country’s massive expansion of access, because they thought it would affect quality. US private universities have mostly kept enrolment growth quite minimal. But chez nous, McGill’s increase – the most modest of the bunch – is 30%. Toronto’s increase is 65%, and McMaster’s is a mind-boggling 80%.

Michael Crow, the iconoclastic President of Arizona State University, often says that where American research universities get it wrong is in not growing more, and offering more spaces to more students – especially disadvantaged students. Well, Canadian universities, even our research universities, have been doing exactly that. What we’ve bought with our money is not just access, and not just excellence, but accessible excellence.

That’s pretty impressive. We might consider tooting our own horn a bit for things like that.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post