I was fooling around this weekend with some data on public higher education funding for HESA’s forthcoming publication World Higher Education: Institutions, Students, Finances. For the most part, the report’s data shows that funding around the world continues to increase, but not always enough to offset student number growth or inflation. It’s not flashy growth, but it is fairly consistent.

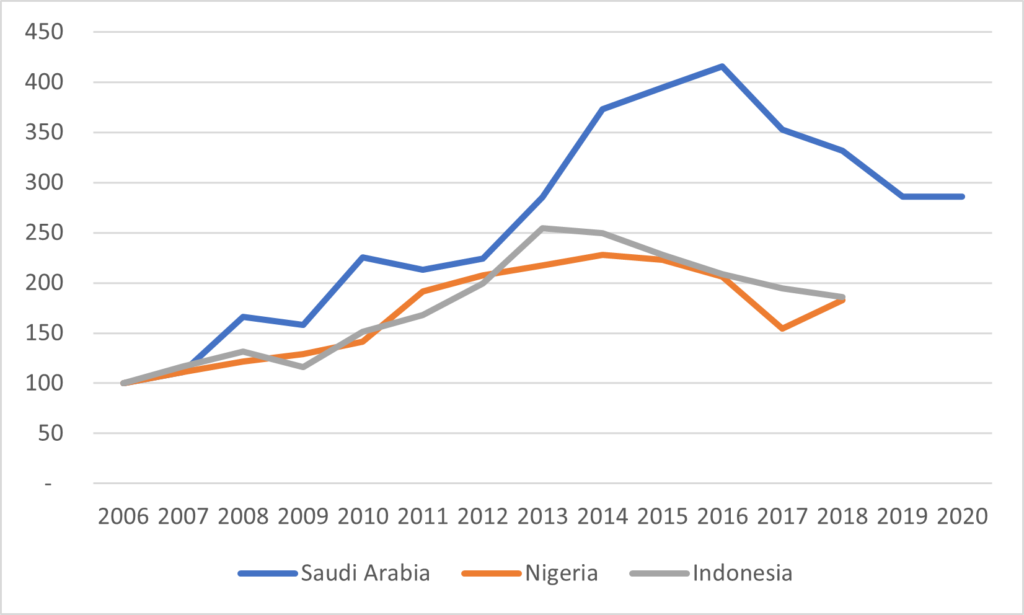

There are three significant exceptions: Indonesia, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia, all of them OPEC members. In these countries have recently seen huge drops in funding. Now, to be clear, in all three cases, their current levels of spending on higher education are way above where they were when the big run-up in oil prices began in the mid-00s. But also in all cases, their public expenditures have fallen from where they were when the oil boom ended. Take a look at Figure 1, which shows each country’s trajectory of public expenditure on higher education in inflation and purchasing-power-parity-adjusted terms, indexed to 2006.

Figure 1: Total Public Spending in Constant $PPP, 2006=100, selected OPEC countries

The dates of peak higher education spending vary, and data availability varies quite a bit as well, but the picture across all three countries is remarkably similar.

- In Indonesia, the peak came soonest, in 2013. Funding rose 150% (again, this is in inflation-adjusted terms) in the preceding seven years and then fell by about 25% thereafter.

- In Nigeria, the peak came in 2014. Spending rose by 130% in the previous eight years before falling back by a third in the following three years.

- In Saudi Arabia, funding rose by – hold onto your hats – 315% between 2006 and 2016. However, since then, funding has fallen by 28%.

Why did spending stay buoyant for a couple of extra years in Saudi Arabia? I don’t follow events in the Kingdom closely enough to say for sure, but my guess would be that a) King Abdullah was quite enamoured with expanding higher education funding and the budget was untouchable until his death in 2015, and b) Saudi cash reserves were such that they could maintain spending in the hopes of a medium-term oil price recovery in ways that the Nigerians and Indonesians could not.

This shouldn’t be all that surprising. Petro-dollar dependent countries tend to have boom-bust public sectors as well as private ones. Still, these are huge, huge cuts that are incredibly difficult to absorb if you’ve committed money during the upswing to hard-to-reduce expenditures like salaries.

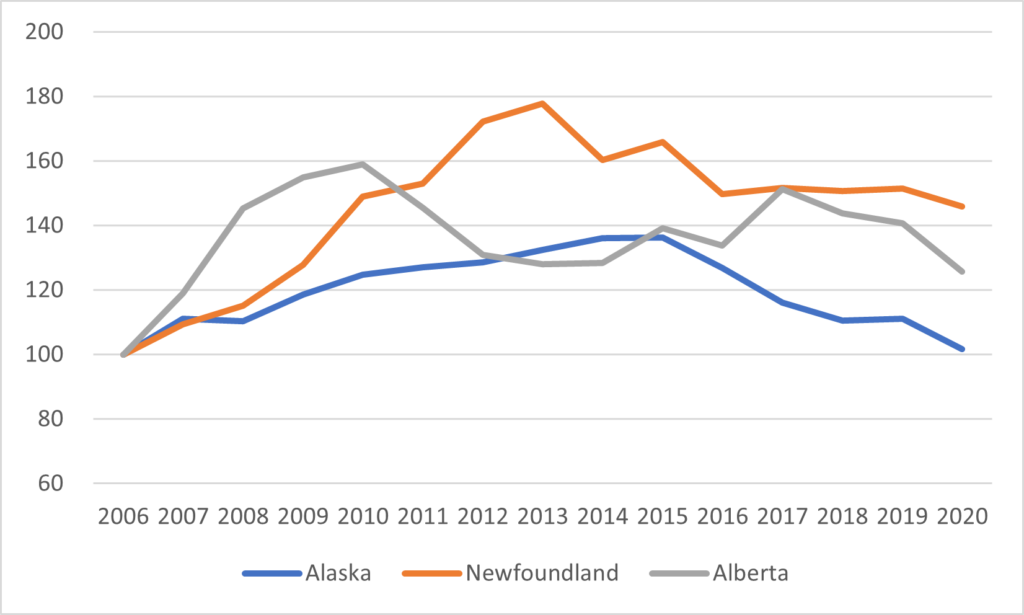

These countries are hardly alone in this predicament. In North America we also have some jurisdictions which are pretty hydro-carbon dependent: in particular: Alaska, Alberta, and Newfoundland & Labrador. Figure 2 shows the path public spending on higher education has taken in these jurisdictions.

Figure 2: Total Public Spending in Constant $PPP, 2006=100, Alberta, Alaska and Newfoundland & Labrador

In brief:

- Alaska had a 40% increase in funding between 2006 and 2015 before giving back all those gains from 2015 to 2020.

- Alberta’s big peak was in 2010, just after prices for natural gas peaked (Alberta’s provincial finances are more geared to gas than to oil). Spending rose 60% (!) in the four years between 2006 and 2010, evidence that Ed Stelmach was more like King Abdullah than you’d think. Spending fell a bit then increased early in the NDP government’s tenure, primarily to pay for a four-year tuition freeze rather than fund institutions. Between 2017 and 2020, funding fell by almost 20%.

- Newfoundland is maybe the most interesting of the trio. Between 2006 and 2013, funding rose by 80% in real terms. It then fell by about 16% over the next three years before plateauing. Funding dipped again a bit in 2020, and according to the plan laid out in last year’s budget it is due to plunge another 15-20% or so between now and 2026, which would bring total expenditures down to about the starting point (although with the rebound in oil prices, we’ll see if the provincial government decides to stay the course on cuts or not)

The thing is, though: higher education institutions – and especially universities – are not really made to ride budgetary roller-coasters like this. Their cost structures are brittle and inflexible, and even the tiniest cuts tend to send the system into convulsions. Really, institutions in jurisdictions where income is highly tied to natural resources should be allowed or even encouraged to put money aside in some kind of fiscal stabilization fund in order to make sure that the highs do not go too high and the subsequent pull-backs do not go too low. I don’t mean into endowments, because the rules for getting money out are too complicated: I mean a genuine rainy-day fund. For the sake of long-term stability, universities in these jurisdictions need to give up the sugar-highs of funding upswings, and their governments need to make sure institutional funding rules are changed to permit this to happen.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I’d be interested in seeing what the situation is like for Norway. That might imply a solution.

Secondly, I’d not trust anyone to run a true rainy day fund, as you put, without declaring precipitation on the least pretense. That’s why endowments are supposed to be hard to access.