Today, I want to talk a little bit about a region of the world that doesn’t get a whole lot of attention/respect in higher education talk, but which has recently faced some quite unimaginable financial and demographic challenges. The higher education systems of the former Soviet Union and its erstwhile Eastern European allies have been through a wild ride over the past fifteen years and there really has never been another period in higher education history with such a rapid and sustained decline in student populations.

(I will note that the data for this blog comes from HESA’s upcoming publication World Higher Education: Institutions, Students and Finances which will be coming out in January after over three years of preparation. When published, it will be by far the most comprehensive statistical treatment of global higher education anywhere, so as you can imagine I am pretty stoked about this.)

In order to tell the story of the region, I will concentrate on its five largest higher education systems: Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Poland and Romania. And in order to put these countries in some kind of regional and global context, I will compare them not just to each other, but also to the average of major West European HE systems, the average of HE systems across the Global North (which is basically the OECD, plus the Eastern Bloc countries examined here, but minus Turkey, Chile and Mexico for geographic reasons), as well as the global average made up of 56 countries around the world that make up close to 95% of total global enrolments.

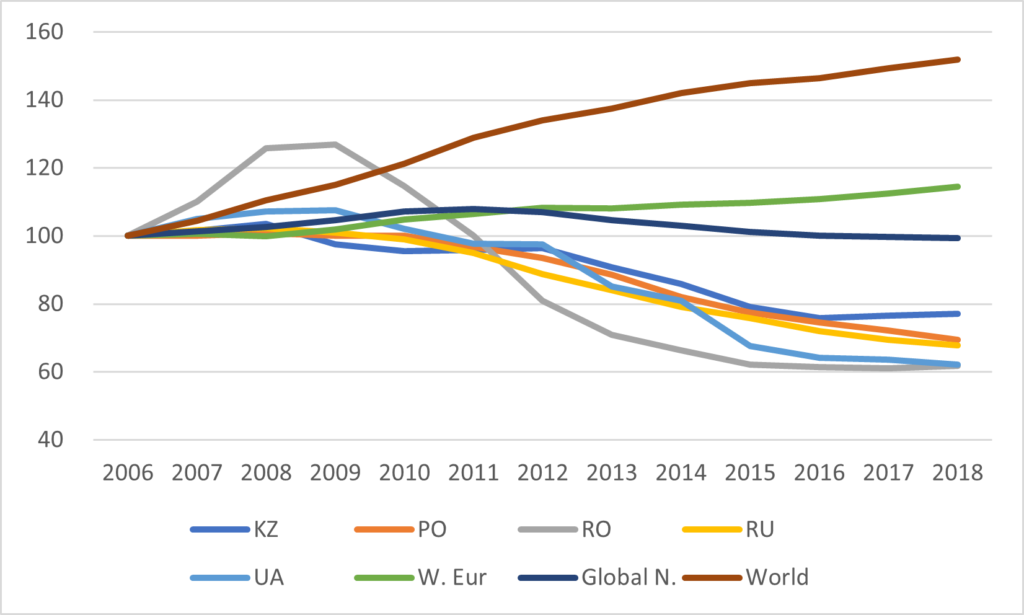

Let’s start by seeing what happened to enrolments. Enrolments in the region boomed in the 1990s and early 2000s, partly because the arrival of a market economy required people to learn new skills but also because enrolments had been restricted under communist regimes. But most countries in the region experienced an enormous drop in the birth rate around 1990. In Romania’s case, that was because contraceptives became available for the first time (these having been outlawed by Nicolae Ceaucescu in 1967); in the rest of the region it was because of declining birth rates in the face of a full-on economic collapse. The consequence of falling birthrates in the 1990s was plummeting enrolments in the 2010s: between 2006 and 2016, no country in the region saw a fall of less than 20% in enrolments; meanwhile, in Western Europe enrolments rose 15% and globally they increased by more than 40%.

Figure 1: Change in Total Enrolments, Former Eastern Bloc and Comparators 2006-2018, (2006 = 100)

Source: HESA World Higher Education Database

(If you’re wondering why Romania looks a bit anomalous, it has to do with a very strange private institution named Spiru Haret University, which by 2008 was enrolling close to a third of all students in Romania. The only trouble was that it was basically a degree mill, and as the government belatedly started to shut down some of its more obvious low-quality programs, students fled. That, combined with the demographic transition, resulted in a reduction in the number of students being cutin half between 2009 and 2013, which I am fairly sure is the biggest peacetime enrolment collapse anywhere in the world, ever.)

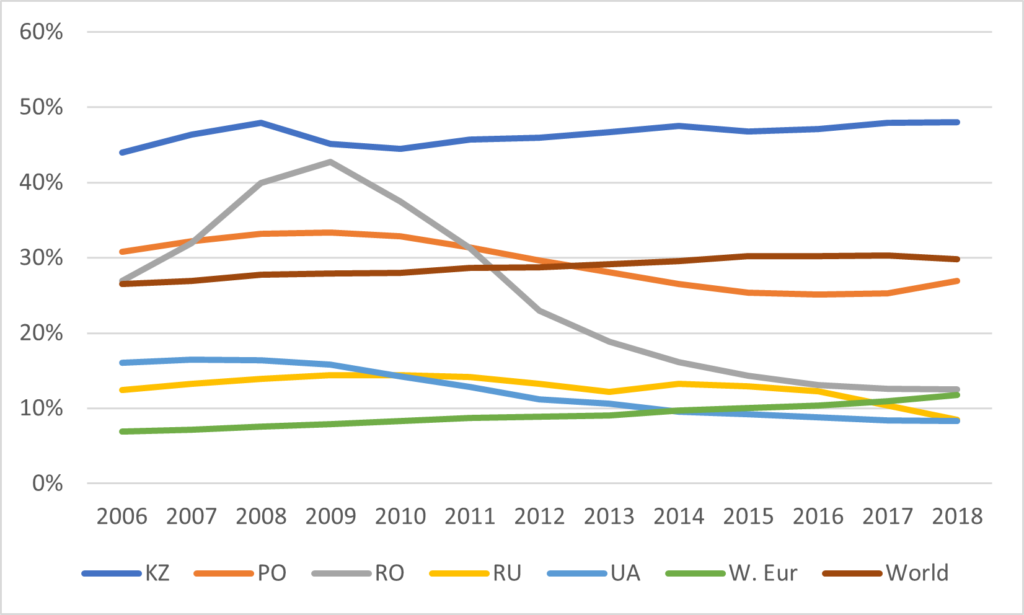

Figure 2 shows the percentage of students in private higher education. Private higher education had long been a bigger deal in Eastern Europe than in the West, in part because public universities couldn’t cope with sudden boom in demand for higher education on the budgets they were able to wrest from cash-strapped governments. Further, in the social sciences, public universities had limited credibility after teaching “scientific socialism” for 40-70 years and private alternatives looked pretty good. But the same privates that rose during the boom years also took the majority of the hit when students disappeared. The big exception here is Kazakhstan, where private universities maintained a 50% share of enrolments more or less throughout the period 2006-2018.

Figure 2: Proportion of Students in Private Higher Education Institutions, Former Eastern Bloc and comparators, 2006-18

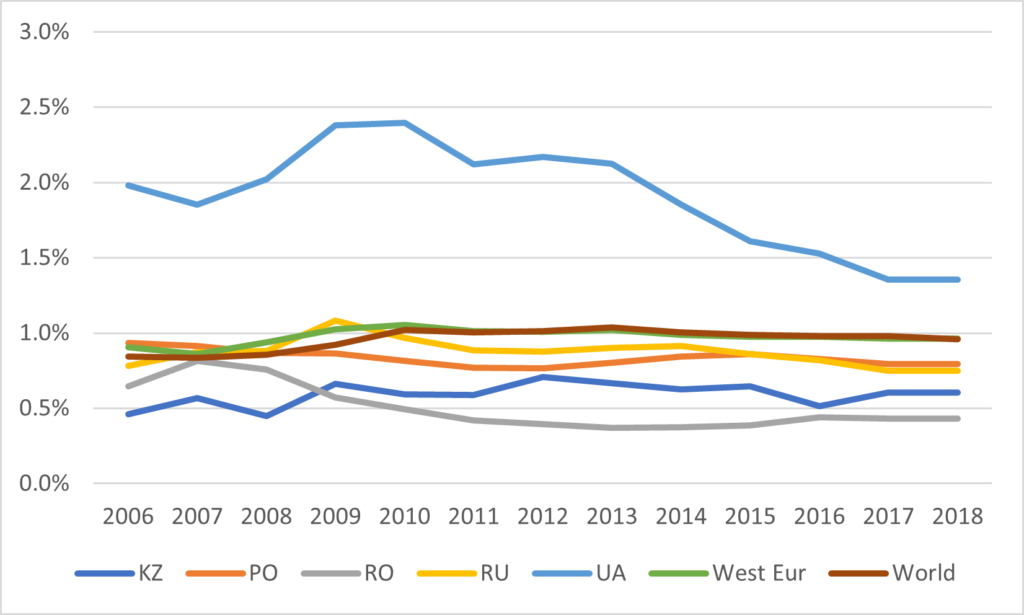

Figure 3 shows public expenditures on higher education as a percentage of gross domestic product. Generally speaking, countries from this region spend slightly below the global average (and well below the West European one). The real outlier here is Ukraine, where spending was at Scandinavian levels, at least until the Donbas War began in 2014, after which it began falling towards the regional average.

Figure 3: Public Expenditures on Higher Education as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, Former Eastern Bloc and Comparators, 2006-18

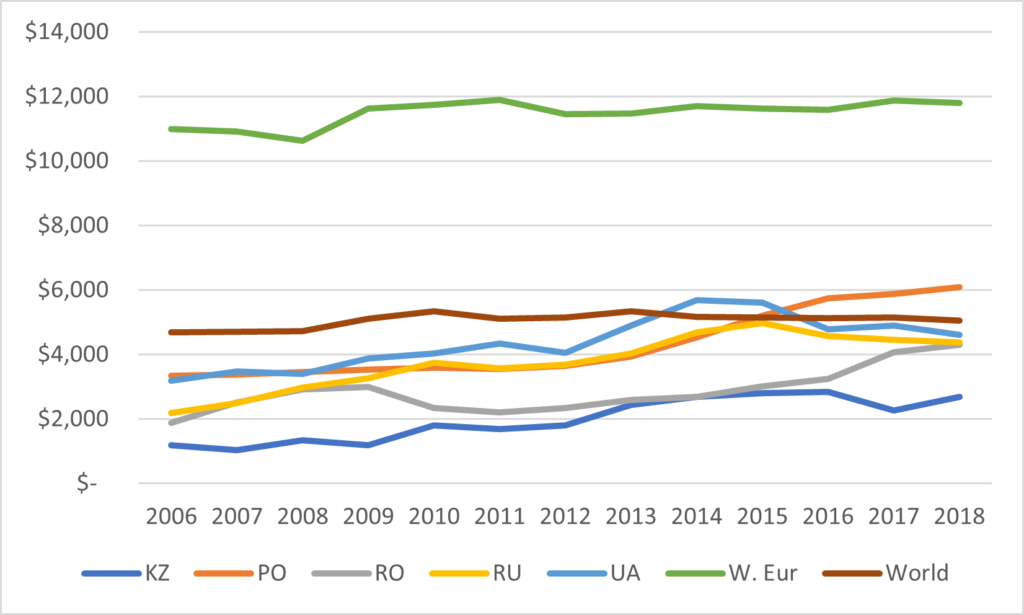

Spending on a per-student level tells a different story: per-student expenditures rose (albeit from a low base) while West European and World totals are declining slightly. Remember, there are a couple of things going on here. The first is that economies in this region are in catch-up mode and have therefore tended to grow faster than elsewhere – so holding student numbers constant, you might still expect per-student numbers to go up faster in Eastern rather than Western Europe. But then, recall that the number of students is falling quickly, too. So even though funding levels are relatively stable, funding per-student is rising quickly, doubling in Russia and Romania, and rising sharply in the other countries, even Ukraine. Those levels are still a very long way off Western European standards, but they have at least started to approach or peek above global levels.

Figure 4: Per-Student Public Expenditures on Higher Education in constant 2018 USD at PPP, Former Eastern Bloc Countries, 2006-18

Finally, there is the question of what the future holds. If student numbers keep falling, then this improvement in per-student expenditure can keep going, right?

Well…

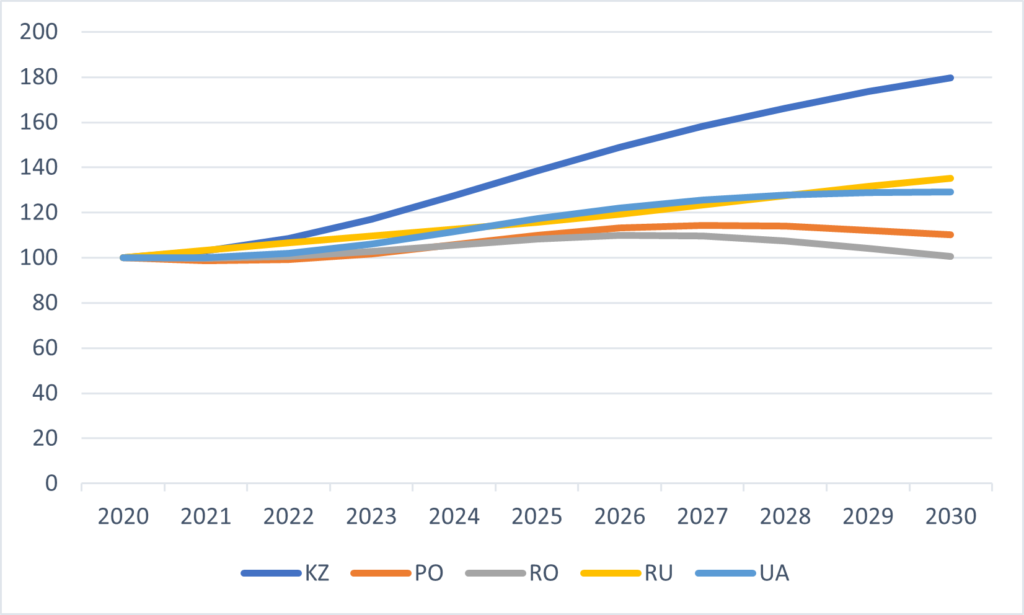

Figure 5: Projected Population aged 18-21, Eastern Bloc Countries, 2020-2030 (2020 = 100)

Here you realize all these countries started to really diverge in the mid-2000s. Poland and Romania, the two countries that gained access to the European Union, did actually see a brief rise in birth rates in the early 2000s, but this pretty much tailed off by the time of the great financial crisis, and so for the late 2020s, we see these countries youth populations start to shrink again. Russia and Ukraine saw much stronger and more sustained rises in their birthrates: their youth populations are looking at increases of 35% and 29%, respectively over this decade. That’s not enough to reach replacement rate, but it is enough to give their universities a lot of work to do, and it’s not clear yet where the money for that will come from. And finally, there is Kazakhstan, where the youth population is expected to increase by 80% (not a misprint) over the decade. Keep an eye of that country: I suspect there will be quite a lot of policy innovation to work out how to deal with what are clearly going to be some eye-watering numbers with respect to student demand.

In short, then, even after fifteen roller-coaster years for higher education, at least of a few of these countries still have some big challenges to meet.

The blog will be off next week: see you back here on October 25th.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thank you, Alex, for another great and informative piece.

And special thank you for writing about the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. This part of the world does not get much attention in Canada, and when it does, it’s rarely about evidence and almost always about politics and, in general, full of uninformed rant.

Your article is refreshing (to be fare, your entire blog is), both in tone and content, and provides great insights grounded in quality research.

Bravo and thank you again!