Yesterday, we saw how tax credits lowered net prices by refunding students (or their families) roughly one out of every three dollars spent on tuition. But that’s not the whole story, because there are a lot of university students who also get some form of non-repayable assistance (i.e. grants); for them, tuition is even lower.

Let’s start with Quebec, where net tuition after tax expenditures is a mere $1,555. Data from the latest Aide Financiere aux Etudes annual report, adjusted for known changes in student aid expenditures, suggests that somewhere in the neighbourhood of 50-55,000 university students are receiving grants, which, on average, are worth $6,380 apiece. Meaning that net tuition for grant recipients in Quebec is in fact negative $4,825.

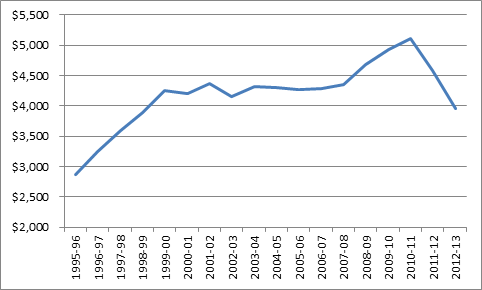

In Ontario, net tuition after tax credits is $5,680. Everyone with a family income under $160,000 is eligible for the Ontario Tuition Grant, which is (effectively) worth $1,730. So that means that, in fact, for a considerable majority of the full-time undergraduate population, net tuition last year was is $3,950, which is lower than it’s been at any time since 1998-99.

Figure 1 – Net Real Tuition in Ontario, After Tax Credits and Tuition Rebate, 1995-96 to 2012-3

Here’s where the analysis gets tricky. In the CSLP zone, many people receive more than one grant, mainly because of the overlap between federal and provincial aid. But while we know the average size of each grant, there’s no method of working out how many of the 320,000 recipients of federal grants (who receive on average 1.18 federal grants each – you can get more than one) also receive one of the 250-300,000 provincial grants.

However, based on a little bit of policy analysis – and some phoning around to friends in provincial governments – I reckon that between half and 2/3 of all provincial grant recipients are getting federal aid, as well. That would give us a ballpark of about around 430,000 total grant recipients, of which roughly two-thirds are in universities. With roughly $1.2 billion being given out in the CSLP provinces, that suggests that the average grant recipient there receives about $2,800.

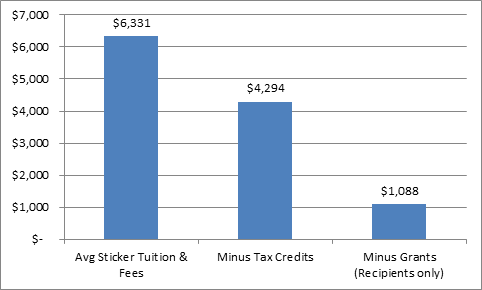

Taking that data and merging in the Quebec numbers gives us the picture we see in Figure 2:

Figure 2 – Actual Net Costs, Canada, 2012-3

Across Canada, the sticker price of tuition and fees last year was $6,331. As we saw yesterday, that falls to just over $4,300 when you take tax credits into account. And that’s the real net cost for about two-thirds of the full-time student body. But for the other third, the third that gets grants, real net tuition averages just over $1,000 – and it would appear that for a substantial proportion of these students, the actual cost is negative.

So, when the Statscan tuition numbers come out, just remember: no one actually pays the amounts Statscan reports. Most students pay about 66% of the sticker price, and the neediest third (proportions may vary by province) pay about 17% of the sticker price.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Is there a similar analysis anywhere of comparative borrowing costs over the sarm period? Even if you accept the repeated mantra that “student debt keeps rising” the cost of acquiring and carrying that debt must be remarkably lower for those graduates who have only ever known interest rates to be historically low, etc.

Ask and ye shall receive, Mark. https://higheredstrategy.com/a-closer-look-at-student-debt-postscript/

Wait, that’s the wrong link. Try this. https://higheredstrategy.com/a-closer-look-at-student-debt-part-1/

Reminder: Here in BC, student loan borrowers who are in programs less than two years are not eligible for the low income grants.

International students make up a big chunk of these students, so is it still correct to say that $4,300 is the real cost for about 2/3 of the student body, or just 2/3 of the domestic student body?

I’m quoting domestic tuition rates only here.