Back in July, I was kindly invited to a conference sponsored by the Perspektywy Foundation in Warsaw to give a talk about the future of global higher education after COVID. Over this week, I want to recap that talk and provide some analysis about the main policy trends affecting higher education of the next few years. Not all these trends will affect countries equally (for reasons that will become apparent) but I think they probably capture the biggest pieces of the puzzle through to 2025 or so.

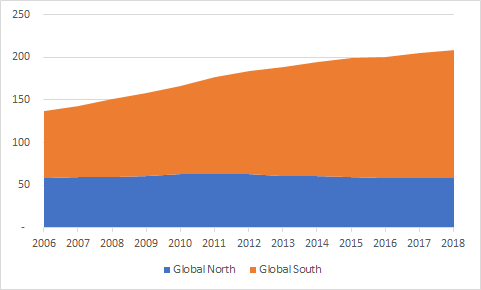

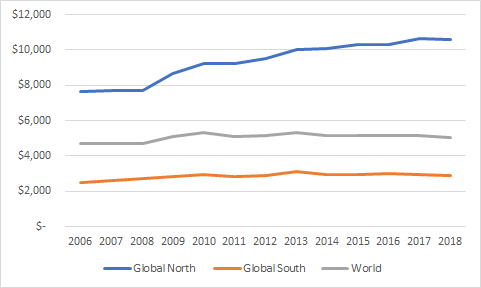

Being (sort of) a historian, my instinct when approaching these kinds of questions is to look at what was going on in terms of enrolments and public funding prior to COVID. And the answer, as Figures 1 and 2 show, is in particular due to developments in Russia and the United States, student numbers were slumping in the Global North (that is, what we used to call the “developed world”) while growing at a good but slowing clip in the Global South (basically Latin America, Africa and the later-developing bits of Asia) and also that public funding per student was flat in real terms in the Global South was flat while increasing in the Global North (albeit partly because student numbers were declining there).

Figure 1: Number of Students, in Millions, by Global Super-region, 2006-2019

Figure 2: Total Public Expenditures Per Student, in Billions of constant 2018 USD at PPP, 2006-2018

(If you think the above figures are cool, sit tight. Resident HESA genius Jonathan Williams and I are putting out a report on global higher education enrolments and finance in the next few months that will knock your socks off)

So then COVID hits. Now, for me, the most important thing to remember is that a *lot* went on during COVID besides just COVID. And with respect to higher education, I think there are three big developments worth noting. The first is the more or less overt outbreak of a Cold War between China and the West. We now see endless stories about universities – in Canada, in the US, and especially in Australia – needing to tighten up their own security against potential Chinese industrial espionage. And in retaliation we are seeing things like China breaking off large numbers of international education partnerships, and recommending Chinese students not to enroll in Australian universities (we won’t be able to fully test how effective that measure is until 2023, because at the moment Oz doesn’t seem likely to be out of quarantine until after the 2022 school year starts).

China is incredibly important to the global higher education picture, and not just because it represents close to 20% of all students and is the #2 country in terms of science output. Chinese students abroad have had an enormous role in financially propping up the higher education systems of several anglophone countries, including our own (If I am not mistaken, students from Greater China – i.e. including Hong Kong – are now the largest single source of income for the University of Toronto, larger than either the provincial government or domestic students). More importantly, a very large proportion of STEM-subject labs in North America depend on the labour of Chinese graduate students. If the flow of students from China ends, not only are a lot of institutions going to be in trouble, but a big chunk of the continent’s scientific infrastructure would be in peril as well, which in turn would have significant effects on our larger innovation pipeline as well. (To be clear, I’m not saying this will happen. I’m saying the odds of this happening have grown significantly in the last few months),

The second big development was the ongoing deepening of culture wars. Quite obviously, there have always been differences between les wokes and les Duplessistes. But what has happened in the last 24 months or so has been an obvious escalation, and more importantly, one in which the right has declared open war on higher education in many countries (Hungary and Russia have been most obvious about it, but you certainly see this tendency in Australia, the UK and the US as well). In truth, it’s a conflict between governments and the humanities and (a bit) the social sciences, and an awful lot of it is focused either on gender studies or history – universities are just collateral damage, in this respect.

Universities weathering political storms are nothing new. But in most countries, universities have prided themselves on being a neutral forum, a place which can serve their countries no matter who is in power. But that is harder to do when one set of political parties – often the ones in power – are actively identifying universities as “the enemy”. Universities are still adjusting to this new and (in democracies at least) unprecedented situation.

The third development is what the massive expansion of higher education and science spending in the United States is going to do. I outlined much of the new Biden agenda, particularly with respect to big new investments in community colleges, student aid and science back here. While not all of it will pass, a lot of it is going to go through and that is big news.

Internationally, some parts of this package are neither here nor there. Much of it is about replacing private expenditures on higher education with public ones – it’s not going to make a positive impact on institutions’ bottom lines (though possibly the focus on community colleges and the completion agenda might create some policy mimetics in a few countries around the world, including Canada). But the big jump in science and technology expenditures are a big deal. They are spooking several countries around the world who may increase their research funding as a result. They up the ante for national investments in scientific research everywhere (including Canada, though none of our politicians seem to have had the wit to notice it). These measures go a long way to restoring some of the luster that top US universities lost over the Trump years and makes it a lot easier to recruit top graduate students. This will have significant effects on global science patterns.

And then, yeah, there was the experience COVID itself. I won’t belabour this too much here because we’ve all lived through the global experiment in remote learning. But the key points is that we have a lot more students (mainly older ones) who think remote learning is a decent alternative to the status quo ante, and – more importantly – a large cadre of instructors who now see the advantages and opportunities of remote teaching and are comfortable and perhaps even eager to continue doing so. I’ve mentioned before how I think just in Canada the potential market for this kind of fully on-line undergraduate degrees could be as large as 200,000 students: someone, at some point, is going to be able to move to grab some of those. And, in theory, there is a big potential market in transnational online education, if – and let me stress this is a big if – western institutions are prepared to reduce the price of their course offerings.

But it’s worth remembering also that governments spent a *lot* of money to get us through the pandemic. We went back to WWII-style borrowing for a year, which was all to the good but compromises the ability of governments to make major new investments in anything in the years ahead (those debts are sustainable if interest rates stay at historic lows, but any uptick leaves public finances in a lot of difficulty). And this, more than anything, is what’s going to create a hard limit on universities plan to grow or improve in the next few years.

The question, of course, is what this mishmash of big developments means for the future of higher education. And to me it seems like the there are three big themes. The first is what I call “Funding Challenges Forever”, the second is “New Pedagogies and New Credentials” and the third is what I call the “Primacy of Politics”. And over the next three days I’ll be talking about each one of these.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I’m not normally one of those annoying people who tell those facing ruin that everything’s an opportunity, but it does strike me that there are some opportunities here, if only for institutions to cure themselves of addiction to foreign tuition and lab labour, and stop trying to solve all problems by turning into unwieldy multiversities.