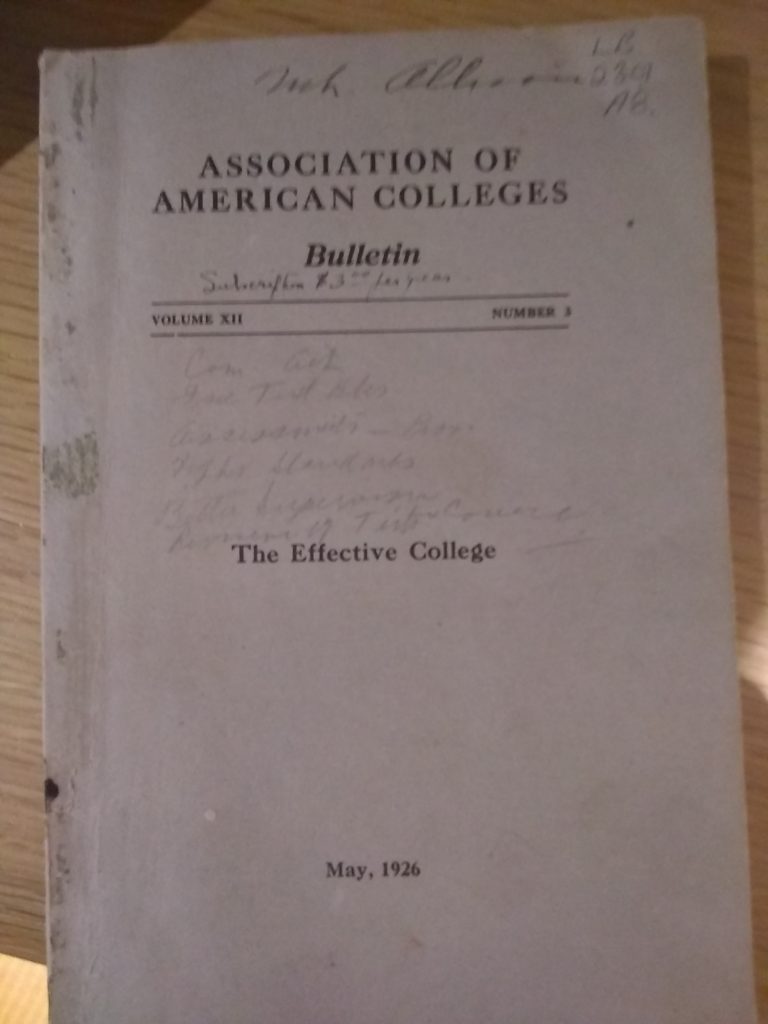

Sometimes when you pick up an old book about higher education, it’s like stepping into a weird version of the present because the issues are exactly the same, only presented in the language of a different decade. The book I picked off the shelf this week, though, is nothing like that – it’s actually a really interesting window into a totally different world of higher education. And it’s actually not a book, but a “bulletin” of the Association of American Colleges (now the American Association of Colleges & Universities) from 1926, on the subject of “The Effective College”.

(Where do I get these things, you ask? I have no memory of picking this one up. Might have been at John King Books in Detroit – a national treasure, if you ask me – which has a lot of stuff like this.)

So, just to back up a bit, the AAC was an association of colleges – a term which in the American lingo of that era implied a) residential and b) not land-grants. And these bulletins, near as I can tell, are almost transcripts of meetings – a series of papers on specific issues which for the most part are best described as well-informed if not scholarly, accompanied by transcripts of the Q & A sessions. The Q & As are particularly interesting because it is clear these are some very senior people (including some Presidents) from very prestigious institutions who bothered to show up and compare notes on things like financial management, athletics, curriculum – all topics which by the 1950s would have had their own specific professional bodies and never would have been taken up in a general meeting.

In fact, at one point in the bulletin, you can actually see the birth of Institutional Research as a profession, when the University of Pennsylvania’s Comptroller starts talking about what the effective college really needs is “a phase of administration which has not yet been charted, that of ‘fact-finding’” and that “sound educational practices today demands an educational fact-finding office…a co-ordinated office of administrative and financial fact-finding”.

The major topic of this meeting was about defining “effectiveness”. Some American higher education history is needed to decipher this. The United States has a lot of colleges, a product of the fact that pretty much anyone could set one up (unlike Europe, there was no need for state approval), and as it happened many, many religious communities did just that. At the turn of the century, the state of Ohio alone had more universities than the entire German Empire. This drove some key philanthropists – Carnegie and Rockefeller in particular – to absolute distraction. And so these two Foundations – vehicles of two capitalists who above all gained their fortune through a rigid attention to details like efficiency – spent a lot of their time in the inter-war period trying to create better systems of education, by pushing private institutions either to merge or to avoid duplication with local competitors. For instance, the Atlanta University Center (a merger of Morehouse, Spellman and Atlanta Universities, all historically Black, later joined by Clark and Morris Brown Colleges) was the result of Rockefeller money; in Canada, Carnegie tried to pull off a merger of Nova Scotia institutions, though in the end the only practical upshot of that effort was to get King’s to move to Halifax so it could share a campus with Dal.

In large part, this meeting was an intellectual riposte to that line of argument. There are passionate debates about the most “effective” size of a college, with people arguing for numbers anywhere between 200 and 500 student. And no, there are no missing zeros in that sentence. The argument essentially was that college is about forming the “whole student” and this, for reasons that now seem a bit mysterious, implied that you needed to teach them in small enough cohorts that they could all know each other and develop an “esprit de corps”. Now of course, anything under 500 students means a college is on a death watch: a better example of the Baumol Effect would be hard to find.

While most of the pieces are merely quaint (I particularly enjoyed the chapter on the new fad sweeping the nation called “Freshman Week”, which intriguingly enough seemed to involve a lot of ability testing), there is one article which is really eye-opening because of the density of the data presented, and the way it allows for comparisons with the present day. There are interesting details on teaching loads, which at the time were commonly measured in “student clock-hours”: that is, number of students in a class multiplied by the number of hours per week the class meets. We are told that 300 clock hours might be the standard at a college of 500, but it would be lower at smaller colleges. Now, today, that would be like teaching two classes of 50 with a standard 3-hours per week contact time, which is not that different from what we see today (though: there was not much research to speak of and no graduate supervision – profs spent a lot more of their time on pastoral work with students back then and also they were not paid nearly as well). The difference though is that generally 300 clock hours meant 3 classes of 20 students meeting for five hours a week (once a day for an hour).

The other really interesting piece of information has to do with finances, and in particular, the calculation that roughly 60% of an institution’s budget went to “education”, with 16% to “administration”. Which is actually uncannily close to what we have today in Canadian universities (59% and 13%, respectively, see back here for the data). To some extent this is probably coincidence – I doubt this guy was using exactly the same definitions we use today to categorize expenditures – but it’s worth a reminder that even when universities were simpler place, a significant chunk of money was going to dreaded “non-academic” expenditures.

Anyways: pre-internet, bulletins were the main way that people learned about leading-edge practice in their professions. As such, they are an interesting and useful window into the ways universities have changed over the past century. Find some and browse them if you can!

Tweet this post

Tweet this post