I spent part of last week at the European University Association’s Funding Forum in Salzburg. Though it’s getting harder to see how you keep a European-wide conversation going when different countries are heading off in such different directions (small increases in funding in Germany and some Nordic countries, versus cuts of 35-45% in Ukraine and Greece), it was nevertheless a pleasant and productive event.

My job there was to give delegates a bit of a pep talk about European higher education, and why it may see better days soon. Sure, they have very big demographic and fiscal challenges, but these days, who doesn’t?

European universities have two big latent advantages over North American ones. The first is their cost structure. As we’ve seen before, European universities have done well to keep their labour costs relatively low. They also have room to squeeze a bit more productivity out of the teaching function by reducing the number of contact hours per degree. Though the numbers differ a bit from country to country, it seems that German and Austrian students, at least, have about 15% more contact hours on the way to a degree than do North American students. Close that gap, and that’s a lot of labour costs potentially saved.

Can this be done without reducing standards? Well, unlike universities here, European universities actually have some objective standards to uphold, thanks the widespread adoption of learning outcomes statements. As a result, I’d back their universities over ours every day of the week to engineer those kinds of efficiencies in a sensible way.

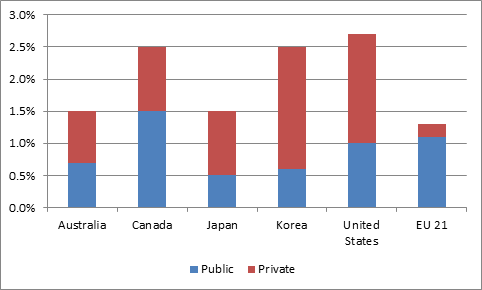

Public and Private Expenditures on Tertiary Education as a % of GDP, 2009

Then there’s the issue of income. European universities have an enormous untapped asset; namely, students. Even if EU members could close half the tuition revenue gap with non-EU OECD members, they would suddenly have enormous new pots of income which they can use to revitalize themselves. Almost instantly, they could go from having systems that are poor (if efficient), to having systems that are genuinely well-funded. The back half of this decade could be an exciting time in Europe, if governments and institutions have the will to grasp this nettle.

Of course, introducing tuition fees is a delicate thing, especially in countries where high unemployment is reducing the obvious payoff to higher education. Not surprisingly, I spent a lot of time there explaining what was going on in Quebec (most were shocked to find out how generous the Quebec government’s package really was). The lesson seems to be that introducing big changes in fee policy requires careful timing and – more importantly – governments with a lot of popular credibility. We might be waiting a while for that in Europe – and in Quebec, too, for that matter.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Any possibility of a breakdown of those numbers between University and College?

As an European academic I should be thrilled by the bright future that Alex Usher predicted for our universities (Europe’s Latent Strengths, June 19). Let me, instead, raise some critical questions.

First, what Alex regards as an “advantageous cost structure” is primarily due to the lower salaries of European academics compared to their North American counterparts. My point here is not to complain how poorly we are paid, but just to raise the question about whether academic salaries in Europe are sufficient to prevent brain drain – that is, the danger that the most competitive academics either leave for the US or for non-academic sectors of the economy in their own country.

Secondly, I was struck by Alex’s comment that German and Austrian students have around 15% more “contact hours” than North Americans. I would be very curious to see a meaningful indicator for contact hours, that is standardized for international comparisons. Lacking such information, I will provide a few personal experiences of the differences between teaching a course in an Austrian and in a Canadian research university. In Austria, in a “seminar” (a course in which as many as 40 students may be enrolled), students are graded at the end of the course on the basis of a paper, almost always without any feedback or justification for the grade assigned. Typically, there are no assignments during the course. Students who do not deliver a paper are not graded, so they do not fail the course; they can easily repeat the course in the next year, which, of course, dramatically increases the number of “contact hours”. There is no need to explain in any great detail the differences between teaching a course at a Canadian university to a Canadian audience. I wonder what consequences it would have on the quality of teaching if Austrian universities follow Alex’s recommendation and start “to squeeze a bit more productivity out of the teaching function.” Another point regarding the contact hours is the number of master and/or doctoral students that faculty in the Austrian system (at least in the “mass studies”, where the ratio between full professors and students may be 1:400) are supposed to supervise. Do North Americans know that at Austrian universities some professors supervise up to 80 master/doctoral students? Nobody has to worry if this negatively impacts the quality of the thesis; after all, it is the supervisor who also evaluates and grades the thesis.

Finally, Alex suggests that the European universities could revitalize themselves by targeting their “enormous untapped asset” and raising tuition fees. He concedes that this is a “delicate thing”, but I would rather call it a “mission impossible”. As the examples of Austria and Germany indicate, even the introduction of rather symbolic fees (370 – 500 € per semester) was reversed in Austria and in most German provinces. Other than in Québec, where students in that respect reflect a rather European attitude, it is not only students, but also political parties – including parties that form the government – that are fundamentally opposed to any kind of tuition fees.

I wish I could share Alex’s optimistic view, but I fear it is based on an excess of wishful thinking.

Hans Pechar, Alpen-Adria University, Vienna location

Hi Hans. Nice to hear from you (and apologies for taking so long to approve this post).

Two quick responses:

1) The contact hours comparisons I was making were based on about a dozen institutional descriptions of how different types of courses with different contact hours translated into ECTS credits. This does vary a bit from place to place – the 15% was an average. Across Europe as a whole I expect there would be quite a bit of variation both in the contact hours and in – as you describe – what happens during those contact hours.

2) Re: fees. This could be wishful thinking, but I have a hard time seeing how Europe – even Germany – gets to the end of the decade without facing this funding problem more squarely. Spain, for instance, is raising fees 30-50% this year – Ireland will almost certainly go down this route soon. I think if the argument in favour of fees (plus of course appropriate student assistance) is made more forcefully, we can see more countries go down this road.