A few months ago I was asked to give a presentation about my thoughts on the “big trends” affecting international education. I thought it might be worth setting some of these thoughts to paper (so to speak), and so, every Friday for the next few weeks I’ll be looking one major trend in internationalization, and exploring its impact on Canadian PSE.

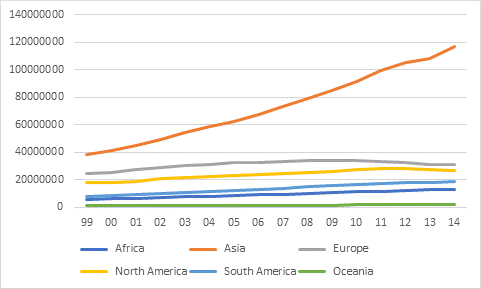

The first and most important mega-trend is the fact that all over the world, participation in higher education is going through the roof. Mostly, that’s due to growth in Asia which now hosts 56% of the world’s students, but substantial growth has been the norm around the world since 2000. In Asia, student numbers have nearly tripled in that period (up 184%), but they also more than doubled (albeit from lower bases) in Latin America (123%) and Africa (114%), and even in North America numbers increased by 50%. Only in Europe, where several major countries have begun seeing real drops in enrolment thanks to changing demographics (most notably the Russian Federation), has the enrolment gain been small – a mere 20%.

Tertiary Enrolments by Continent, 1999-2014:

Now, what does this have to do with the future of international higher education? Well, back in the day, international students were seen as “overflow” – that is, students forced abroad because there were not enough educational opportunities in their own countries. Therefore, many people thought that the massification of higher education in Asia (and particularly China) would over the long run mean a decrease in internationalization because they would have more options to choose from at home.

Clearly the last decade and a half has put that idea to bed. Global enrolments have shot up, but international enrolments have risen even faster. But as all these national systems of higher education are undergoing massification, they are also undergoing stratification. That is to say: as higher education systems get larger, the positional advantage obtained simply from attending higher education declines, and the positional advantage to attending a specific, prestigious institution rises. And while higher education places are rising quickly around the world, the number of spaces in prestigious institutions is staying relatively steady in most countries (India, which is expanding its IIT system, is a partial exception). Take China for example; over the last 20 years, the number of new undergraduate students being admitted to Chinese universities has increased from about one and a half million to six million per year. In that same time, the intake of the country’s nine most prestigious universities (the so-called “C-9”) has increased barely at all (it currently stands at something like 50,000 per year).

Now if you’re a student in a country where there’s a very tight bottleneck at the top of the prestige ladder, what do you do if you don’t quite make it to the top? Do you settle for a second-best university in your own country? Or do you look for a second-best university in another country, preferably one where people speak English, and preferably one which has a little bit of cachet of its own? Assuming money is not a barrier (though it often is) the answer is a no-brainer: go abroad.

So when we look ahead to the future, as we think about what might affect student flows around the world, what we need to watch is not the rise of university or college places in places like China and India, but rather the ratio of prestige spaces to total spaces. As long as that ratio keeps falling – and there’s no evidence at the moment that this process will reverse itself anytime soon – expect the demand for international education to remain high.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The neo-elitism that is a covert result of massiifcation is rarely identified, let alone discussed. Good catch!