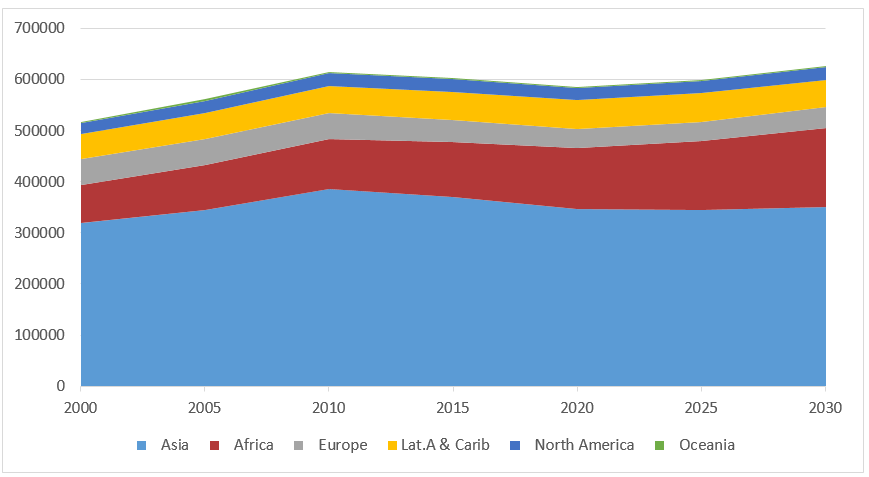

Last week I noted that one of the big factors in international education was the big increase in enrolments around the world, particularly in developing countries. Part of that big increase had to do with a significant increase in the number of youth around the world who were of “normal” age for higher education – that is, between about 20 and 24. Between 2000 and 2010, that age-cohort grew by almost 20%, from a little over 500 million to a little over 600 million. Nearly all (95%) of that growth came from Asia and Africa.

Figure 1: Number of People Aged 20-24, by Continent, 2000 to 2030

But as figure 1 shows, 2010 was a peak year for the 20-24 age group. Over the course of the 2010s, numbers globally will decline by 10%, and not reach 2010 levels again until 2030 (intriguingly, this is almost exactly true for Canada, as well). A problem for international higher education? Well, maybe. Demography isn’t destiny. But to get a bit more insight, let’s look at what’s happening to the demographics within each region.

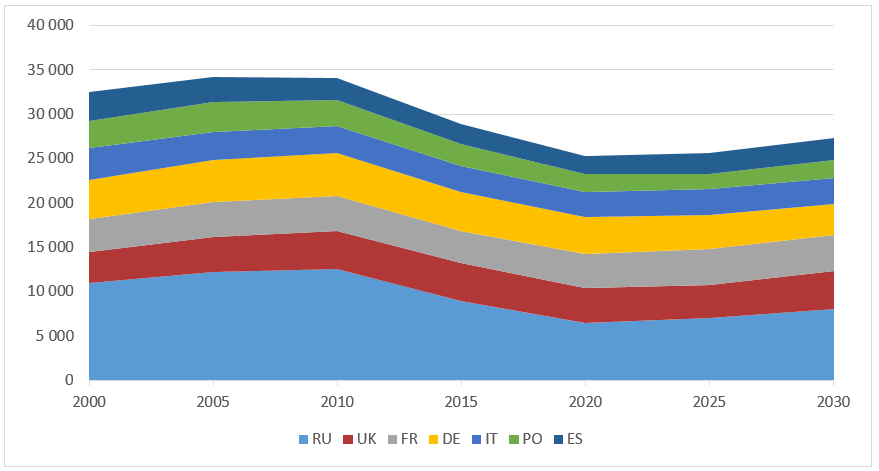

In Europe, the numbers for the 20-24 year old group are falling drastically. In Western Europe, the decline is relatively moderate and reflects a gradual drop in the birth rate which has been going on for about fifty years. In Eastern Europe, the fall is more precipitous, a reflection the fall in the birth rate during the occasionally catastrophic years of the switch from socialism to capitalism. In Russia, youth numbers are set to drop by – ready for this? – fifty per cent (or six million people) between 2010 and 2020.

Figure 2: Number of People Aged 20-24, Selected Countries in Europe, 2000 to 2030

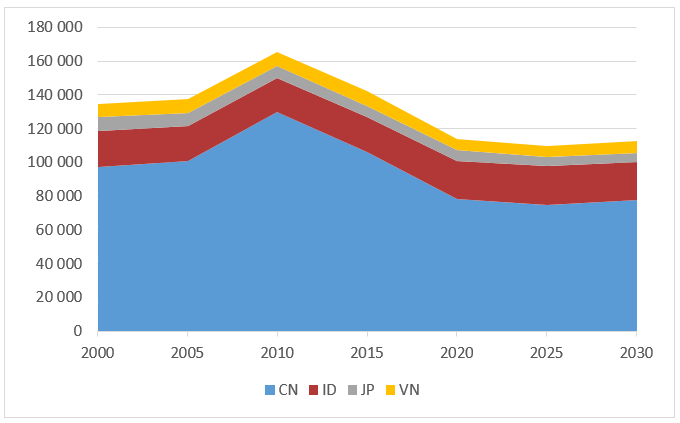

In East Asia, the story of the first ten years of the century was the huge increase in youth numbers in China (yes, the one-child rule was in effect, but the previous generation was so large that raw numbers continued to increase anyway). But once we reach 2010, the process reverses itself. China’s youth cohort drops by 40% between 2010 and 2020. Similarly, Vietnam’s drops by 20%, as does Japan’s (which additionally lost another 20% between 2000 and 2010). Of the countries in the region, only Indonesia is still seeing some gentle growth.

Figure 3: Number of People Aged 20-24, Selected Countries in East Asia, 2000 to 2030

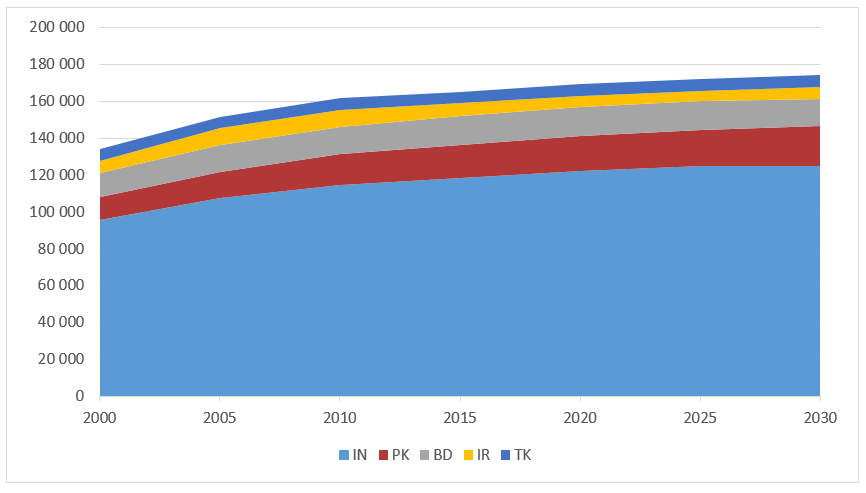

The story changes as we head west in Asia. India will continue to see rises – albeit small ones – in the number of youth through to 2030 at least. Pakistan will see an increase of 50%, albeit from a much smaller base. Numbers in Bangladesh will rise fractionally, while those in Turkey will stay constant. Iran, however, is heading in the other direction; there, because of the precipitous fall in the birth rate in the 1990s, youth numbers will fall by 40% between 2010 and 2020 (i.e. on a similar scale to China) before recovering slightly by 2030.

Figure 4: Number of People Aged 20-24, Selected Countries in Southern & Western Asia, 2000 to 2030

I’m going to skip the Americas, because numbers there stay pretty constant over the whole period and the graphs therefore look pretty boring (just a bunch of lines as flat as a Keanu Reeves performance). But here comes Africa, where youth numbers are expanding relentlessly.

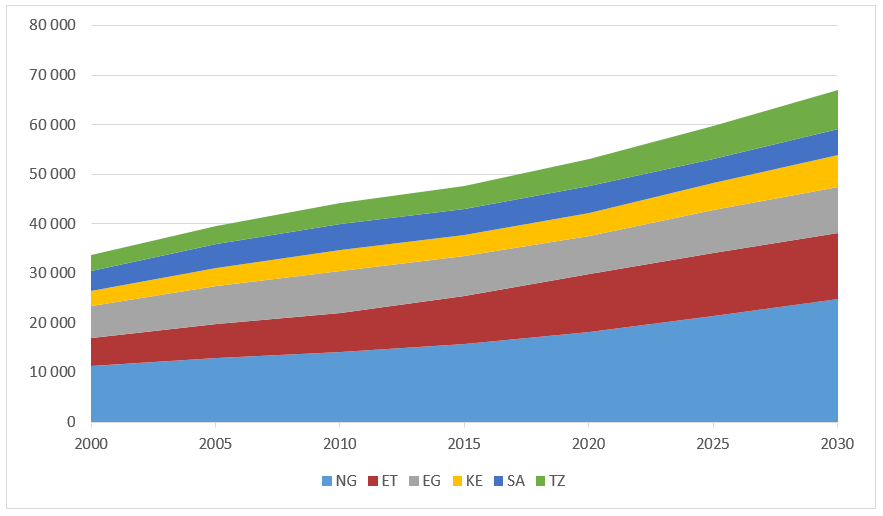

Figure 5: Number of People Aged 20-24, Selected Countries in Africa, 2000 to 2030

The six countries portrayed here – Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania – make up just 40% of the continent’s population, but they are quite representative of the continent as a whole. By 2030, there will be more 20-24 year-olds in Nigeria than there are in North America, and growth in numbers in Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia (as well as Nigeria) between 2015 and 2030 will exceed 50%. The outliers here are South Africa, where youth cohort numbers are going to stay more or less constant, and Egypt, where the numbers drop in the 2010s before starting to grow again in the 2020s.

So what can we learn from all this? Well, what it means is that overall, youth numbers are shifting from richer and middle-income countries to poorer ones. While many developed countries like the US, France, Canada and the UK are more or less holding their numbers constant (or, more often, showing a dip in the 2010s and a subsequent rise in the 2020s), we are seeing big, permanent drops in numbers in places like Russia, Iran, China and Vietnam and big increases in places like Nigeria, Pakistan and Kenya.

Ceteris paribus, this is bad news for international student flows because on average, the potential client base is going to be coming from poorer countries. But keep in mind two things: first, international education is by and large the preserve of the top five percent of the income strata anyway, so national average income may not be that big a deal. Second, while the size of the base populations may be changing, what really matters for total numbers is the fraction of the total population which chooses to study abroad. China is a good example here: as our data shows, the youth population is falling drastically but international student numbers are up because an increasing proportion of students are choosing to study abroad.

Bottom line: the world youth population is now more or less stable, after decades of growth. For international education to continue to grow means finding ways to convince people further down the income strata that study abroad is a good investment.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One response to “Four Megatrends in International Higher Education – Demographics”