If there’s one word everyone can agree upon when talking about international education, it’s “expensive”. Moving across borders to go to school isn’t cheap and so it’s no surprise that international education really got big certain after large developing countries (mainly but not exclusively China and India) started getting rich in the early 2000s.

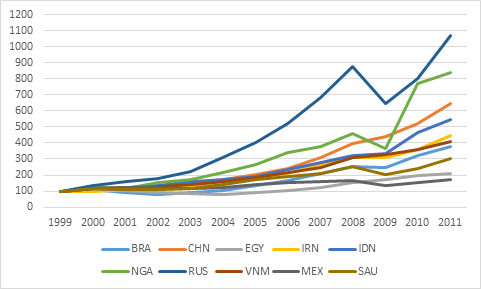

How rich did these countries get? Well, for a while, they got very rich indeed. Figure 1 shows per capita income for twelve significant student exporting countries, in current US dollars, from 1999 to 2011, with the year 1999 as a base. Why current dollars instead of PPP? Normally, PPP is the right measure, but this is different because the goods we’re looking at are themselves priced in foreign currencies. Not necessarily USD, true – but we could run the same experiment with euros and we’d see something largely similar, at least from about 2004 onwards. So as a result figure 1 is capturing both changes in base GDP and change in exchange rates.

And what we see in figure 1 is that every country saw per capita GDP rise in USD, at least to some degree. The growth was least in Mexico (70% over 12 years) and Egypt (108%). But in the so-called “BRIC” countries world’s two largest countries, the growth was substantially bigger – 251% in Brazil, 450% in India, 626% in China, and a whopping 1030% in Russia (and yes, that’s from an artificially low-base on Russia in 1999, ravaged by the painful transition to a market economy and the 1998 wave of bank failures, but if you want to know why Putin is popular in Russia, look no further). Without this massive increase in purchasing power, the recent flood of international students would not have been possible.

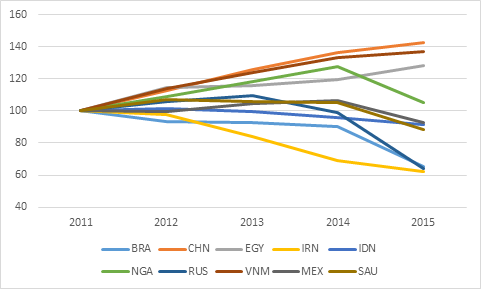

But….but but but. That graph ends in 2011, which was the last good year as far as most developing countries are concerned. After that, the gradual end to the commodity super-cycle changed the terms of trade substantially against most of these countries, and in some countries local disasters as well (e.g. shake-outs of financial excess after the good years, sanctions, etc) caused GDP growth to stall and exchange rates to fall. The result? Check out figure 2. Of the 10 countries in our sample, only three are unambiguously better off in USD terms now than they were in 2011: Egypt, Vietnam, and (praise Jesus) China. Everybody else is worse off or (in Nigeria’s case) will be once the 2016 data come in.

Now, it’s important not to over-interpret this chart. We know that many of these countries have been able to maintain. Yes, reduced affordability makes it harder for student to study abroad – but we also know that global mobility has continued to increase even as many countries have it the rough economically (caveat: a lot of that is because of continued economic resilience in China which has yet to hit the rough). Part of the reason is that if a student wants to study abroad and can’t make it to the US, he or she won’t necessarily give up on the idea of going to a foreign university or college: they might just try to find a cheaper alternative. That benefits places which have been pummelled by the USD in the last few years – places like Canada, Australia and even Russia.

In short: economics matters in international higher education, and economic headwinds in much of the world are making studying abroad a more challenging prospect than they did five years ago. But big swings in exchange rates can open up opportunities for new providers.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thanks, very interesting data. Just one observation, “IDN” is the ISO code for Indonesia, not India.