One of the things I am proudest of in my career is the role I played – almost 20 years ago when I was at the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation – in trying to start a tradition of evidence-based research in Canadian higher education. And by evidence-based, I don’t just mean creating better statistical bases to describe systemic inputs and outputs, I mean actual experimental evidence regarding how certain treatments/policies work.

For those of you not up on the concept of experimental evidence in the social sciences: imagine a vaccine trial, in that you take a group of volunteers and randomly split then into two groups receiving different “treatments”, with some getting the drug and others a placebo. It’s almost exactly like that, except that it’s not “blind” (i.e. people know whether they are in the treatment group or the control group). Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee won the Nobel Prize in Economics a few years ago for using these kinds of methods to create better poverty reduction policies in the developing world.

(To anyone inclined at this point to claim “but you can’t run experiments in public policy! It’s immoral to give benefits to some people and not others”: we run experiments all the time. Every time we change a policy, it’s an experiment. We just don’t usually bother to figure out if the treatment actually achieves its aims or not. Because you know, God Forbid we measure anything or suggest in any way that the act of throwing money at a problem is not in and of itself a solution, which seems to be the official position in Ottawa these days.)

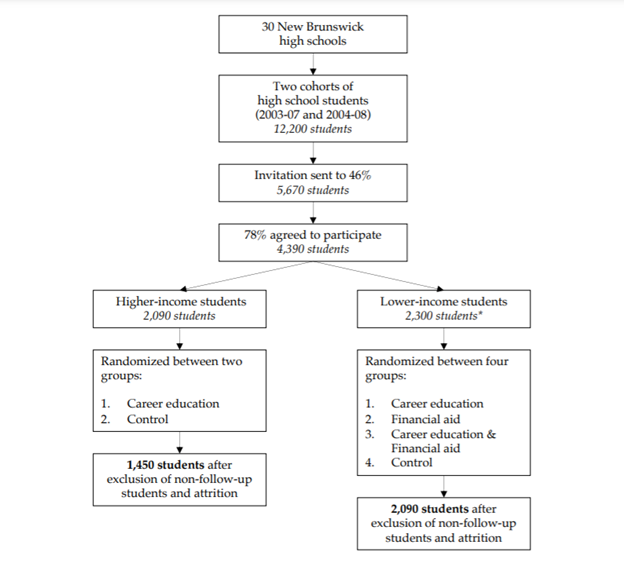

In any case, one of the experiments I worked on (but which other more talented than I brought to fruition – y’all know who you are) was called Future to Discover (FTD). The Foundation paid for it, the Government of New Brunswick hosted it and the Social Research and Development Corporation (SRDC) managed it. The experiment was designed to test the effect of both career guidance and the promise of financial assistance on post-secondary access and participation. Four thousand five hundred students were randomly assigned to receive a series of 20 education/career planning workshops over four years, some of which were also delivered to parents. The low-income students in the experiment were also randomly assigned to receive a grant for post-secondary education worth $8,000 ($2,000/year for up to four years), meaning that there were actually three treatment groups: one receiving career information, one receiving financial support, and one receiving both. And some were assigned to a control group which received nothing.

The results of this experiment on post-secondary access have been known for some time and have written up by the Social Research and Development Corporation on a few occasions: (see Ford, Hui and Kwakye, 2019 for the project’s final report). The short answer is that both interventions increased access, and by a similar magnitude. The career planning changed the type of education students accessed – more university and less college, while the boost in financial aid tended to result in an increase in college attendance (interestingly, both effects were slightly more apparent among francophones than anglophones). The effect of both on graduation was also positive but more muted (the career planning intervention more so than the financial aid one). Interestingly enough, the effect of combining the two forms of interventions did not increase enrolment or graduation by much more than supplying either intervention on its own.

(One really interesting finding in the report is that receiving $8,000 made no difference whatsoever in students’ employment income. That is, giving them money made them no less likely to try to find work. This is significant since one of the touted benefits of grants or lowering tuition, cf. the Labour Government in New Zealand, is that lower net costs will help students work less and study more. Nuh-uh. Turns out students’ drive for a better material standard of living outweighs the drive to study.)

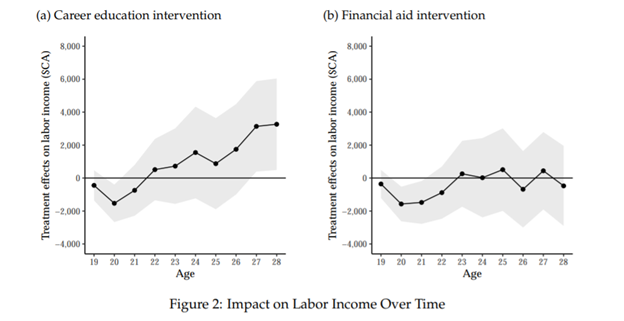

Anyways, just last month, almost a decade after those students left post-secondary, a new study has come along to tell the story from an even longer-term perspective. Laetitia Renée, a PhD student in Economics at McGill University, released a job market paper which focuses on long-term labour market outcomes. She has managed to take all the experimental data and link it to individual files in StatsCan’s Post-Secondary Student Information System and its Tax Filer Database (data nerds will know how insanely cool that is, others will need to trust me). Her focus is on long-term labour income, and what she finds is, well, pretty stunning. It’s most easily expressed in the following graph:

On average, the students who received the career education intervention saw a rise of $3,300 in their income at age 28 compared to the control group. Given that these students only saw a 0.24 rise in their average years of education (remember, many of them would have gone to post-secondary education anyways), that implies a return of over $14,000 per year of education, if delivered with in conjunction with career education. Which is crazy high. But the students who received financial aid? They had no difference in income vis-à-vis the control group, which may suggest a) in the absence of career information, they chose less-remunerative fields of study and/or b) they took some or all of their educational benefits in non-pecuniary form.

Anyways, there are a plethora of lessons for access and student aid policy which could be drawn from the FTD if anyone chose to do so: the main one obviously being that career development information seems to be a much cheaper way to achieve an increase in participation and young workers’ wages (though financial aid does seem to play a large role in retention). Maybe the interesting question for political scientists and policy types is why no one seems to be paying attention to such an abundantly clear empirical conclusion.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This is a very important post, Alex. As a long-time advocate of career development for university students, I am happy to see this study, and thank you for summarizing it.

I wonder if you can send the email version out again, because the mailout had a first paragraph from a different blog post, so you might have lost some readers.

As someone who is interesting in doing research in careers, this is really cool! Especially that both anglophones and francophones were included.

Could you tell me if it was strictly quantitative data? Or where could I find the methodology?