Written in collaboration with Michael Sullivan

Good morning, all. Today’s blog is a collaboration with my colleague Michael Sullivan at the Strategic Counsel (with whom we at HESA Towers have been doing some joint projects over the past year or so) and it’s about the results of a new recently completed survey, which looks at students’ learning experiences since the start of this academic year. It’s an interesting half-full half-empty story, but with some very important future implications.

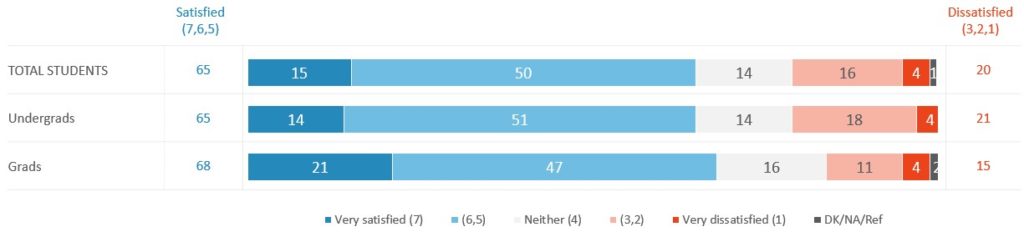

Figure 1 shows the big, top-line results. About two thirds of students say they are “satisfied” with their education since September, which is down a bit on a regular year. Only one-sixth or so say they are “very satisfied” (higher among graduate students), which is balanced out with a similar number who say they are dissatisfied and a smaller number who say they are “very dissatisfied”.

Figure 1: Levels of Satisfaction With 2020 Fall-Term Experience (7 point-likert scale), Canadian University Students, n=1341

Digging beneath the surface though, there are many signs that the experience is far from satisfying. Let’s key in on three specific areas: accessing student/academic services, overall campus life, and the actual learning environment.

Start with services: Two-thirds of students have accessed some university services in the first term, with library and research support services (36%) academic advising (33%) and health and wellness services (22%) being the most frequently accessed both online and in person. Not unexpectedly, more have accessed services online (64%) than in person (42%). Overall, the academic support services seem to be the area where students are most satisfied with university efforts; that said, a substantial proportion express a preference for health and wellness services being accessed in person and given the nature of these services this may not be surprising. And it is precisely these health services which seem most in demand at the moment: one troubling aspect of the move online is how it added to the stress levels of students. In all two thirds agree that they ‘feel more stressed than normal as a result of the shift to online learning’.

If any one issue seems especially troubling to students, it is the loss of an overall campus experience. In all, three quarters (77%) agree that they ‘miss being on campus’ and 48% strongly agree. Further, large majorities report that they are not satisfied with either the opportunities to participate in co-curricular activities and clubs, etc. (68%) or the opportunities to socialize with other students outside of classes (71%). The inability of the online experience to really replicate one essential part of a collegiate experience – close connection with other students – is no doubt a major factor in the overall lower levels of satisfaction we are seeing this year. This finding underlines the importance of on-campus activities for students & confirms that for most students, university is not just about acquiring skills and knowledge in class, but about the maturation and growth gained through interactions outside the classroom.

That said, the pining for a return to campus is not quite universal. Part-time students in particular do not seem to miss campus life as much, with only 31% strongly agreeing that they miss being on campus. These students are generally older (52% being 23 or older compared with 25% among full time students) and of course have responsibilities, expectations and reasons for attending university which are quite different, on average, from full-time students. This group is important, and we’ll come back to them in a second.

With respect to the learning environment, only about half report giving a 5 – 7 on the satisfaction scale for both online classes and labs. Intriguingly, this is not only for online students, but also for those attending at least some classes in-person (presumably the social distancing mask wearing make in person constraining also). But even these numbers hide a good deal of disquiet. This drops to 40% who agree (and 13% who strongly agree) that they ‘like online classes.’ The factors that appear to make online less than ideal for most students include the workload, the level of interactivity in online classes, limited opportunities to collaborate on projects and converse with other students in the class, the quality of feedback on assignments and the lack of motivation. In all cases, about half report these as issues.

Now, all of this said, one question struck a very interesting note. We asked students if they were to take the same courses again, how would they prefer to take it: entirely in person, mostly in-person, an even mix of in-person and online, or mostly or entirely on-line. And though you might expect a huge rush to “100% in person”, you’d be wrong: in fact, only 26% of students plumped for that option, with another 22% saying they would like to take it mostly in person. Fully 20% said they would prefer to stick with a mostly/entirely online format. Now it’s not clear from this whether the reluctance to go back to in-person was due to fear of COVID, or because of genuine preference for the format. But that’s still an important number. In fact, using an index based on three questions in the survey, The Strategic Counsel estimates that roughly a third of all students can be said to have on balance positive beliefs about the remote learning in the wake of the COVID crisis.

This is one of these places where university leaders need to focus on absolute numbers rather than percentages. Yes, on average, students would prefer to be back on campus. But depending on what percentage you want to use to represent students who might want to continue with an online experiment, nationally, we are talking about 200,000 to 400,000 students who might be open to making remote education a permanent part of their education. Even if you take the more conservative number (always the right choice in higher education), that’s a simply massive potential client base for a university that wants to go big into remote instruction. Such a move would not be easy, and it might not be possible for all universities (smaller ones would lack the capital resources, prestigious ones might not want to be seen to dilute their brand). But if one or two of them make the right investments, the rewards are potentially very, very high.

There is, of course, lots more information in the survey, including factors that can enhance the quality of the online learning experience. The information can also be used by any school as a great national benchmarking-tool for institutional quality-control efforts. If interested in purchasing the survey results, or getting a hand with your own survey efforts to compare with these benchmarks, please get in touch with us at info@higheredstrategy.com

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One response to “Examining Learning Experiences During COVID”