Yes, this again. Why? Because a few weeks ago the feds released an economic analysis of the benefits of Innovation Superclusters (recently rebranded as Global Innovation Clusters to make them sound slightly less ridiculous). It’s horrible analysis, but since this topic unites my twin pastimes of making fun of crap economic impact analysis and crap pseudo-industrial policy, I could not resist.

Some background: early in the Liberals’ first term, they announced that the key to growth was clusters – that is, dense, spatially bounded groups of firms in a related industry (think Waterloo and tech). While there was no previously recorded experience of government directly funding clusters into existence, the kinds of targeted industry areas had cluster characteristics, so the idea of spending nearly a billion dollars to try to will these things into existence didn’t seem totally outlandish.

The problem came when this idea ran headlong into the Ottawa regional development policy-making monster, which imposed two conditions on the whole exercise. First, there could not just be five clusters, there must one cluster per region (as Ottawa defines the term “region”, which is a whole other story). And in fact, they couldn’t actually be spatially-bounded clusters, either they had to serve the entire region. The first killed the idea of actual merit-based competition, and the second idea undermined most of the logic behind clusters. What we ended up with was a set of five industrially-thematic regional granting councils, each with its own bureaucracy that took a year or more to set up, creating its own competitions for money for smaller consortia of businesses and post-secondary institutions.

This might all have been tolerable if the responsible Minister, Navdeep Bains, hadn’t tried to launch the whole thing in such a farcical manner. After all, there are worse ways government can spend money than funding partnerships between Canada’s better manufacturers. But no, the Minister for Shaking Hands with Tech Bros had to go and claim that each one of these clusters would result in a “made-in-Canada Silicon Valley” and that collectively, they would see a 50-fold return on investment within ten years (I worked out the implied annual ROI to about 49%/year). The auditor general would go on to accuse ISED of basically pulling these numbers out of its ass and having no plan to measure return.

But now – NOW – we have something purporting to be an impact study, from Ernst & Young. The study is composed of two parts: one utterly laughable, allegedly measuring aggregated economic impact of the superclusters using an input/output methodology, and the other a moderately useful examination of each supercluster based on participant surveys. It’s worth delving into the details of the survey first to see how firms involved in the projects actually experienced the project.

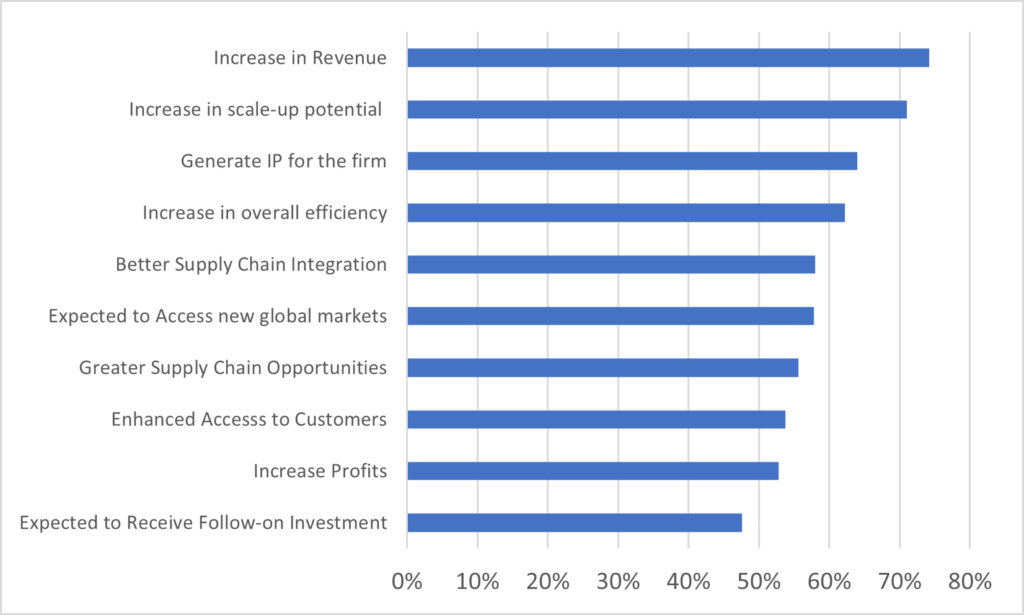

I’ll start by saying that although data was collected and displayed for each of the five superclusters, most of the results are consistent across the clusters. Figure 1 averages out some of the main findings from the surveys across all five clusters (though Ernst and Young seems not to have used quite the same instrument in all clusters, so sometimes the results are averaged over four clusters instead of five). A little over 70% of firms across all clusters have observed or expect increased revenue because of participating in a supercluster initiative, and about seven out of ten see an increase in scale-up potential for their businesses. After that, things get a bit murkier. A little over 60% say they expect to produce IP out of their project, and between 50-60% think their projects have had beneficial results with respect to accessing new customers, new markets, better supply chain opportunities and overall efficiency. However, only about 50% of firms say they expect increased profits and fewer still expect the results of their project to lead to any follow-on investments.

Figure 1: Percentage of Firms Saying that Their Participation in a Supercluster Project Had or Is Expected to Have the Following Effects (Average across clusters)

One may wonder: are these results good or are they bad? Is this a sign of performance or underperformance? I have no idea. Is a 48% rate of companies saying they do not expect any profits from their involvement with the projects a bad thing because it implies a high failure rate, or is it a good thing, because it implies the superclusters are taking risks on projects and companies are learning from failure? You could make either argument, I think, but you’d need more data (and a less foolish success criteria than “Made-in-Canada Silicon Valley”).

Now we get to the fun part, which is the calculation of aggregate economic impact. As I noted above, ISED has made some outlandish claims about the returns on the original $950 million investment. The specific claim (details back here) was that the five clusters would, ensemble, raise net employment by 50,000 and increase GDP by $53.5 billion. It’s not clear how much of this was expected three years into the process, but EY tries answering the question anyway, at least with respect to jobs (the report does not attempt to quantify GDP impact). And the answer is – according to the All-Knowing Ones at EY – 23,877 in the short term, and anywhere from 35,039 to 58,758 in the long term (and yes, they really do have the hubris/ignorance to purport to know this accurately to the final digit).

But how did they get these numbers? Well, it’s important to know that in no way shape or form did they ask any of the companies about their hiring record. They could have, but they didn’t (or if they did, they did not report it). Instead, they chose to use a simple input/output tool which i) treats all costs as benefits, ii) uses a Keynesian multiplier to estimate the impact on GDP and then iii) uses another algorithm to translate GDP growth into tallies of direct jobs (those hired directly by companies with supercluster money), indirect jobs (people who work for other companies who sell things to these companies) and induced jobs (the knock-on effect in the economy of people with direct and indirect jobs eating at restaurants, buying clothes, etc.) In other words, those 23,877 current jobs are not based on any kind of census but are simply the result of plugging in total expenditures to a formula. Any other use of $950 million in the scientific/technical space would give you the same result: it proves absolutely nothing about the efficacy of super-clusters as a use of public money.

As for the longer-term projections, here’s how EY describes its methodology:

Long-term employment contributions were projected by extending the short-term impact projections using composite growth rates that are specific to each Supercluster’s project portfolio. Each funded project was reviewed and assessed for its long-term potential; projects expected to have sustained impact were mapped to their corresponding industries. Composite growth rates were developed based on data from research reports regarding expected market growth for the mapped industries. Scenario analysis was also conducted to illustrate how changes in technology adoption rates could affect the ISI’s projected impacts.

I get that consulting companies don’t like to give away their IP but this is some deeply unconvincing hand-waving. It looks suspiciously like there is cherry-picking going on with respect to which projects get included in the long-run growth average, and the long-run growth average itself looks to me like it’s just “hey, we found a report saying jobs in the protein industry are going to grow at 7% per year, let’s apply that assumption to all the protein companies in our sample!”

I am honestly not sure what any of this tells us about super-clusters. A review after three years, eighteen months of which was dominated by COVID, seems unlikely to actually tell us anything useful, even if it were more rigorously conducted.

But I do know what it tells us about the culture of evaluation within the Government of Canada, and hoo boy it is not good.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Evaluation studies like this, trying to pin down exact job numbers generated by projects/spending that are still ongoing, are fiendishly difficult to do well. There are just so many unknowns and so many intervening variables. If you’re leading such a study, often the best you can do is lay out your assumptions and (many) caveats and come up with a very rough indicative output number. At least PwC had the sense to build a margin of error into their long term job forecast. But if they’ve churned out these numbers by feeding data into a black box proprietary input-output model, it doesn’t help anyone understand the mechanics of what’s going on in these projects, let alone have much confidence in the final jobs claims. A good evaluation should help you understand the journey, not just the destination. A better approach would have been to dive into a broadly representative selection of case study projects, carry out some mixed methods analysis (including surveys and interviews), and understand what’s really going on in these projects from a theory of change perspective. Crucially, this might have told us (and the supercluster mandarins) about what works best in project design, at least from a job creation perspective. Seems like a missed learning opportunity.