It is a truth universally acknowledged that, first, Canada is facing something of a demographic trough with respect to young people, and second, that this the reason domestic enrolment at the post-secondary level is slumping.

Except, no. The first was true 10-15 years ago, and while the second might still be true, it’s about to change in a hurry. I wrote about reversing demographic trends a couple of years ago, but everyone could use an update because change in this area is about to speed up very quickly and many of the planning assumptions everyone has been using are about to change.

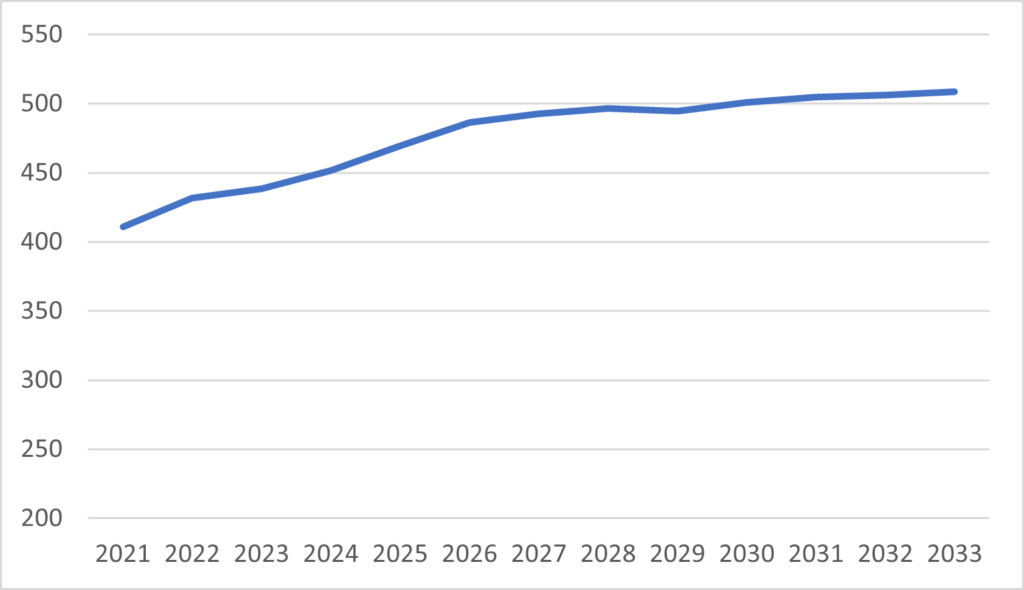

Let’s start just by looking at the simplest indicator: the number of 18-year-olds in Canada. This data is taken from the Statistics Canada population projection sheets, and I am using the most plain-vanilla “medium variant 1” scenario for population growth. What it shows is that there is a wave of new students heading right towards us. Like, now. The number of 18 year-olds is about to increase nationally by 20% in the next five years before reaching a new plateau around 2027 or 2028.

Figure 1: Projected Number of 18 year-olds in Canada (in Thousands), 2021-2033

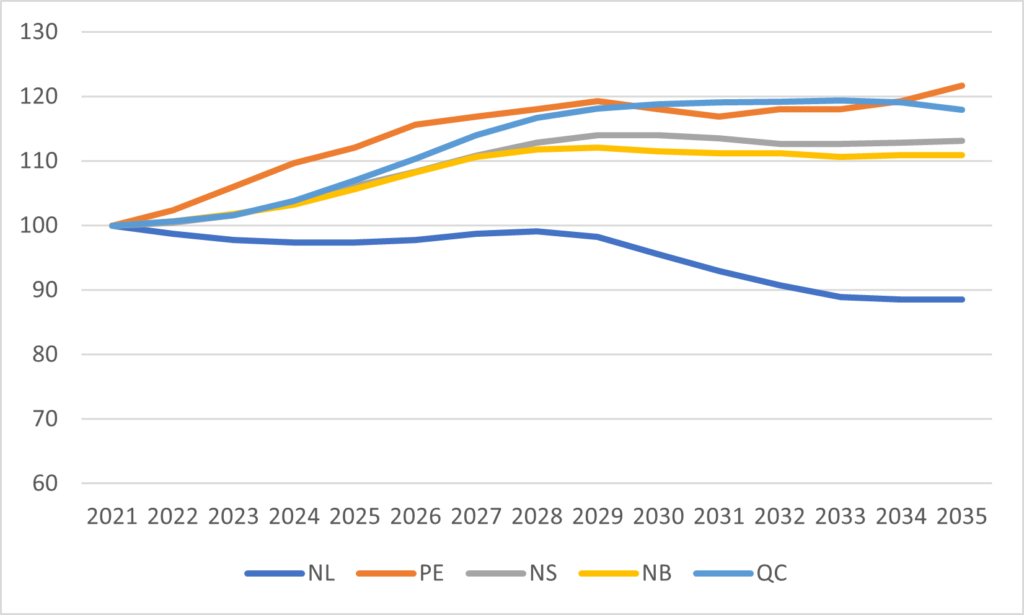

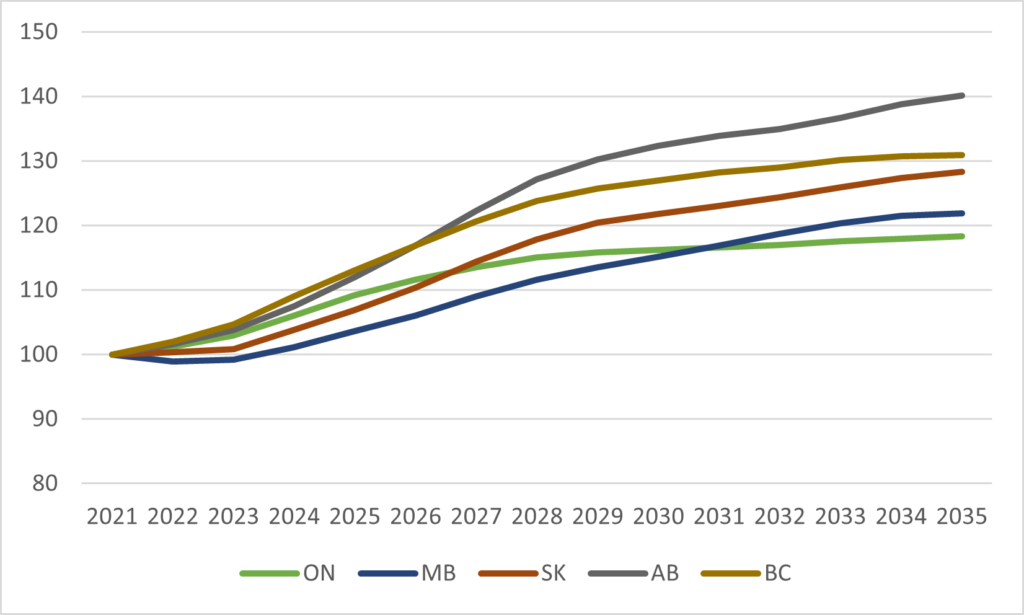

Now, our institutions don’t just teach 18-year-olds, so this doesn’t translate directly into 20% more students in five years. Also, this trend isn’t consistent across the country: some provinces will see faster growth, and some will see slower growth. So, to get a better sense of what’s about to happen, I have graphed the growth of the 18-21 population (still the core years, by far) for every single province from now until 2035. This larger group age-group takes a little bit more time to reach the plateau (2030 rather than 2027), but 20% increase is identical.

Figure 2: Projected change in number of 18-21 year-olds, Quebec and Atlantic Provinces, 2021 to 2035 (2021 = 100)

Figure 3: Projected change in number of 18-21 year-olds, Ontario, Prairie Provinces and British Columbia, 2021 to 2035 (2021 = 100)

First: note that the y-axes on these graphs are different, a necessity when the phenomenon being examined are so different. East of the Ottawa river (figure 2), only Quebec and Prince Edward Island are even close to the national average increase. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are both due for smaller increases of around 10 (though not enough to bring their numbers back to where they were in the early 2000s). Newfoundland and Labrador will be flat until the end of the decade at which point the population will face a drop of about ten percent.

But west of the Ottawa river (figure 3)? Totally different story. Ontario is actually going to lag the national average slightly until about 2030, but it will get there eventually. Manitoba will lag the national average for most of this decade, but surpass it in the early 2030s. And then there are Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Alberta, which are not only going to see growth rates at or above the national average, but – and this is the critical bit – aren’t going to see a plateau at the end of their decade. Check out Alberta in particular: that’s a 40% jump in 18-21 year-olds by 2035. This is going to have some significant effects on post-secondary systems across the country: especially in Western Canada, there is going to need to be a significant ramp-up in post-secondary spending quickly if they aren’t going to have troubles come 2026.

But there’s another factor that needs underlining. The demographic trough wasn’t he only big change in Canadian post-secondary education that occurred in the early 2010s. The other was the uptick in international student enrolments. These two things are not unrelated: it was the demographic slump that created the empty spaces for international students to come (some institutions have now gone waybeyond just replacing spaces, of course, but that’s how it started). It is what allowed international numbers to swell while at the same time allowing institutions to say (truthfully, for the most part) that international students weren’t taking away spots from domestic ones.

But now here’s the thing: those days are over. Domestic demand for post-secondary education is about to rise, and the choice won’t always be between an international student and an empty seat: institutions will have to make cold, hard calculations about whether they want to take a domestic student or an international one. The current ratio of international fees to domestic fees is about 5 to 1. And in most provinces, given the way funding formulas work, there isn’t a lot of extra money available for admitting any marginal domestic students (though Alberta has started to move in that direction). In Ontario, for instance, the so-called “corridor” funding model is designed specifically to not give institutions more money if they take on more students. In short: in some parts of the country at least, we have put ourselves in the position of having to accommodate a sudden rush of domestic students while at the same time making it much more advantageous for institutions to take international students than domestic ones.

Institutions will try to square this circle by asking governments to give them more money to bring in more domestic students instead of having to take international ones (Colleges Ontario tried out a variant on this pitch during last year’s election). My guess is that there is zero appetite for that in most governments. The path of least resistance would be for governments to keep budgets frozen – or maybe increase a little to accommodate population growth and then slap hard caps on international enrolment to make sure seats will be available.

The politics of international student numbers are about to get a lot more interesting.

2 Responses

Indeed. And several USA states have capped out of state and international enrolments for some time, while not necessarily increasing state grants correspondingly.

Interesting contrast to a recent Vox article on U.S. demographics and projections that will affect colleges there.