Let’s start with a little history.

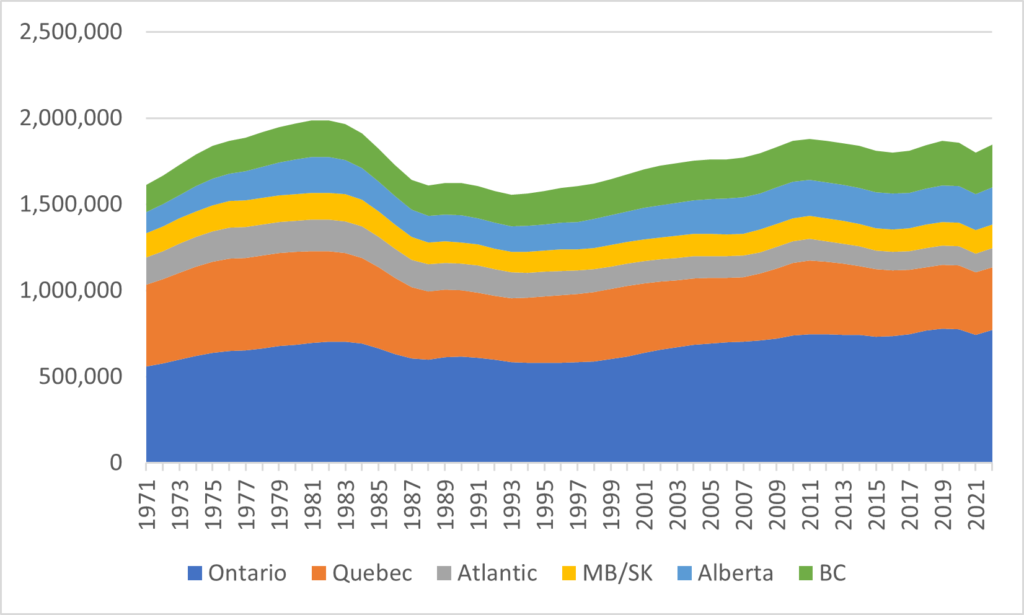

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the youth population (aged 18-21) in Canada from 1971 to 2022. The remarkable thing here is that this demographic group peaked over 40 years ago. What that means is that pretty much all the nearly tripled increase in domestic enrolments in the last four have come from increasing participation rates rather than population growth.

Figure 1: Population Aged 18-21, by Region, Canada, 1971-2022

This growth has not been distributed equally. Youth populations have shrunk substantially east of the Ottawa River and have grown substantially in Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario. Similarly, the vaunted “demographic trough” that was supposed to be affecting domestic enrolments for the past decade or so – that never happened anywhere west of the Ottawa river. The reason? Mainly, rising immigration, which increased the number of young people in the country but especially in Alberta, BC, and Ontario.

Figure 2: Population Aged 18-21, by region, Canada, 1971-2022, indexed to 1971

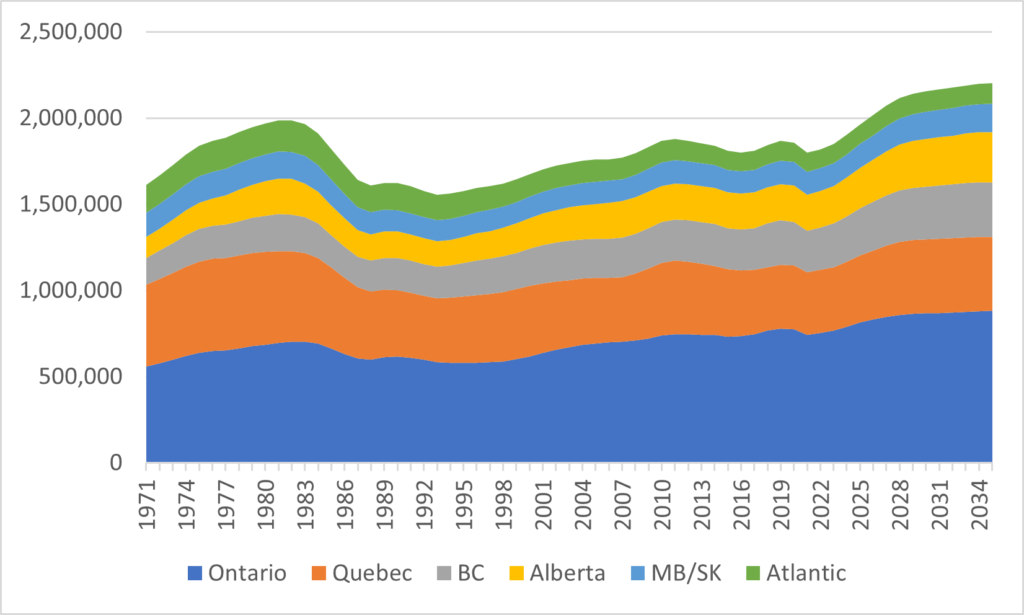

Let me draw your attention back to a graph I published last year, figure 3, which shows Statscan medium-growth (M1) population projections for through until 2035. The entire country is on a significant youth growth spurt from now until the end of the decade (and I have a feeling these projections are going to be on the low side, because Statscan undershot its growth projections for 2022). Nationally, we are looking at a 20% jump in the size of the youth population between 2020 and 2030, in Alberta, it’s an amazing 32%.

Figure 3: Projected Population Aged 18-21, by Region, Canada, 2021-2035, Indexed to 2021

To show that in absolute terms: over the course of the next decade, the national 18-21 population will grow at a faster pace than at any time since the 1970s. And because participation rates are roughly three times what they were back then, you can bet that domestic demand for postsecondary enrolments – undergraduate university enrolments in particular – is going to rise pretty much in lock-step with these increases.

Figure 4: Population Aged 18-21, by Region, Canada, 1971-2035

So what are the three provinces most affected by this – Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia – doing to prepare for this? Well, it turns out that they are digging themselves a massive hole. Exactly none of these three provinces are funding domestic enrolment growth. In a couple of cases, ministries are funding some extra spaces in specific programs at specific institutions – almost always in the name of some poorly-defined labour market needs – but generally speaking, growth is completely unfunded. For new students, institutions can only earn what they get through tuition.

Now would be a good time to recall what institutions get in tuition from domestic and international students, respectively, in terms of tuition.

Figure 5: Average Domestic and International Undergraduate Tuition Fees, Selected Provinces 2023.

Got that? Just as we are on the cusp of some unprecedented pressure on university enrolments, just as we need capacity for domestic students, the governments of Alberta, BC and Ontario have BY DESIGN made it 4-6 times as attractive for their universities to accept foreign students as domestic ones. This is a major problem.

There is a real chance that domestic students will be squeezed out of local universities because of the incentives that these provinces have set in play. Let’s see how that plays at the polls. Another possibility is that local universities will be forced to indefinitely accept domestic students at hugely loss-making rates, with predictable consequences for quality. Again, see how that plays out.

This is not an intractable problem. But it means provincial governments need to spend money and take a problem seriously for once rather than tossing up their hands and asking why some other country’s middle class can’t pay for our institutions.

Our lack of investment might just be about to turn around and bite us. Hard.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

On the assumption that international students are drawn towards somewhat different majors than domestic students, it would not be possible to simply replace one with the other. Even if we were willing to create space for rising domestic enrolments by ceasing to accepting international students, that would only free very much capacity space in certain sciences, business and engineering.

The inability of the provinces to keep up with funding domestic students as demand grows will provide opportunities for private institutions to increase their share in the post-secondary space.

Interesting. Will we have a “University of California versus Government of California”-type situation in some provinces?

You might think that there should be at least ONE provincial government out there that would not only want to proactively avoid a PSE crisis, but also give its province a strategic advantage by attracting high school graduates from other provinces through a properly supported PSE system.

We had this kind of leadership occasionally in select provinces in the past. Alas, no more.