Last week, the Modi government in Delhi released a draft National Education Plan (NEP). This is a big deal because the last new NEP came out over 30 years ago, and the Modi government has been promising a new one ever since it was first elected in 2014. It’s also a big deal because it proposes some very big things, especially in higher education. But Modi while has a reputation for talking up big goals, his track record on delivery is not quite as impressive. So, the question is: what’s in this new plan for higher education and what are the odds anything will change?

If you don’t want the read the long version, there’s a decent summary here. The basic upshot is that the government wants to:

- Double gross enrolment rates from 25% to 50% between now and 2035.

- Simplify and reduce regulation, particularly to make it easier to set up new universities (unspoken here is that it is private entities that would do most of the setting-up).

- Provide institutions with more autonomy.

- Professionalize academic faculty.

- Restructure curriculum in the direction of US/Canadian higher education, with 4-year degrees, majors/minors and a stronger Liberal Arts component.

- Create a massive new “National Research Foundation” on the model (so it seems) of the UKRI (i.e. One Foundation to Rule Them All, as opposed to a series of separate disciplinary councils), with funds equal to 0.1% of GDP (for comparison, something similar in Canada would about a $2 billion annual commitment, or about five times larger than what the Liberals gave science in the “historic” 2018 budget.

- Double education funding as a proportion of total government expenditures from 10% of public expenditure to 20% in five years. Of the ten-percentage point growth, half is to be directed to higher education.

Obviously these are massive undertakings, both in terms of changing institutional and professional cultures within higher education and changing government priorities. There have certainly been cases where we have seen doublings of expenditure with five years before – including in India – but these tend to occur during periods of rapid economic growth when all facets of public expenditure are expanding. Doubling expenditures on education as a proportion of total government expenditures is almost unimaginable (and, I am fairly certain, unprecedented) because it likely requires actual cuts in other areas of government expenditure, which makes it very hard to contemplate.

But there’s another, more fundamental reason to think this is never going to happen: most education spending isn’t under the control of the all-India government. In total, 85% of all education expenditures occur at the state level, and though it is closer to 50-50 in higher education, there is simply no way that an all-India government can credibly make this kind of spending commitment.

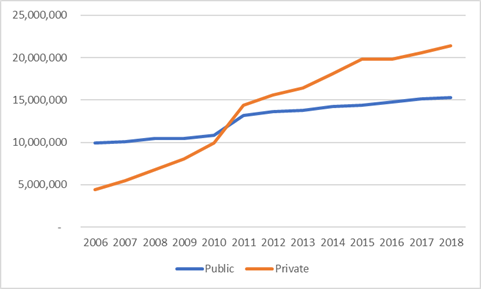

So how do you hit the kinds of targets the government is talking about? Well, take a look at how India has managed its system over the past decade or so. India is the growth success story in global higher education over the past decade or so, with total enrolments rising from about 14 million in 2006 to over 36 million in 2018. But they have done this on the cheap, basically by letting the private sector absorb over three-quarters the of the additional demand. (If you’re wondering why there is a sudden jump of about 8 million students in 2011, it mostly has to do with a shift in the way students were counted, in the sense that everything post 2011 is an actual count by institutions and everything pre-2011 is a straight-up guess based on samples of household surveys: probably the real increase was not quite so dramatic, but look, you work with whatever stats are available).

Students in Indian Higher Education, by sector, 2006-2018

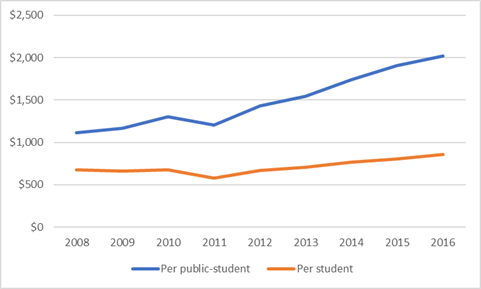

You can see how this plays out in expenditures per student. Even though total public expenditures (central and state combined) doubled between 2008 and 2013, and then increased another 70% or so since then, that all went to a minority of students; the majority paid their own way by going to private institutions. The result was that expenditures per student at public sector institution soared, thus contributing to a perception of increasing quality at select institutions like the Indian Institute of Technology, while expenditures per student (all sectors) stayed more or less flat.

Public expenditures per-student, 2008-2016

Here’s the problem: the NEP is suggesting doubling enrolments again, to around 70 million students per year, by 2030. This would make India the world’s largest HE sector by far; China’s enrolment is only about 45 million and this is stagnant due to demographic challenges. Assuming the all-India government managed to double its contribution, that would only just cover the current rate of per-student expenditure increases in the public sector, leaving almost no money for actual system expansion. Either those costs have to be contained, or it means a minimum of 25 million (and perhaps even 30 million) new students will need to be accommodated by private institutions. In turn, this implies that the private university sector in India alone would be bigger than China’s entire HE system before 2030.

The question is therefore really whether there actually are that many students not currently enrolled in private higher education who might want to attend a private institution. If you say yes: welcome to New Delhi, and there is a very bright future for you flacking for the Modi government. If, like me, you are a bit more skeptical, then what it means is that the growth target is, practically-speaking, unattainable.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post