If there’s one subject we write about that gets people riled up, it’s academic salaries in Canada and the U.S. It’s a complicated issue – so let’s look at concrete examples at three of the better-paying Canadian institutions (Trent, Calgary and McMaster) and three prestigious American universities (Dartmouth, Washington and Berkeley).

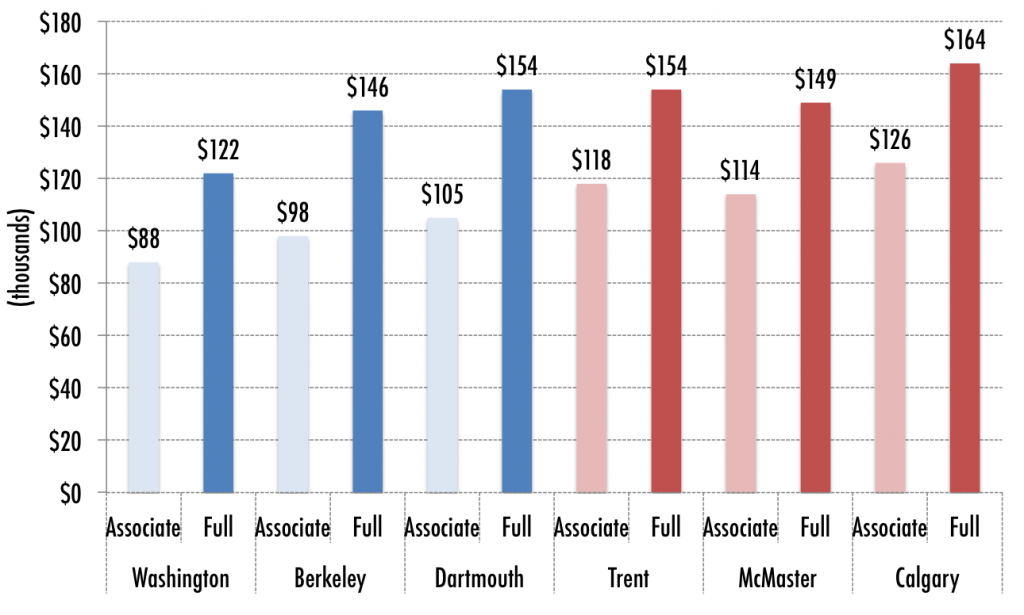

If you just look at baseline salaries for two sets of institutions, you see some pretty big differences as shown in Figure 1, below. The gap is bigger for associate professors than for full professors, but either way, Canadian professors appear to be making out a lot better than American ones.

Figure 1: Unadjusted Average Base Salaries at Selected Institutions, in Thousands of Dollars.

But this isn’t quite the whole story. Our professors get a 12-month salary, and receive the same pay no matter what they do in the summer months. In the U.S., however, pay is on a nine-month basis – in the summer, many profs are working on research and drawing a separate income from their research grant. Different funders have slightly different rules about how much salary professors can take, but the basic rule of thumb – based on National Science Foundation (NSF) rules that came into effect in 2009 – is that they can take another two months’ worth of salary (i.e., 2/9 of their regular annual pay).

How does that affect average compensation in the U.S.? NSF data seems to indicate that about two-thirds of all professors at research universities hold grants. So, multiplying that out, average compensation across all faculty would look like this:

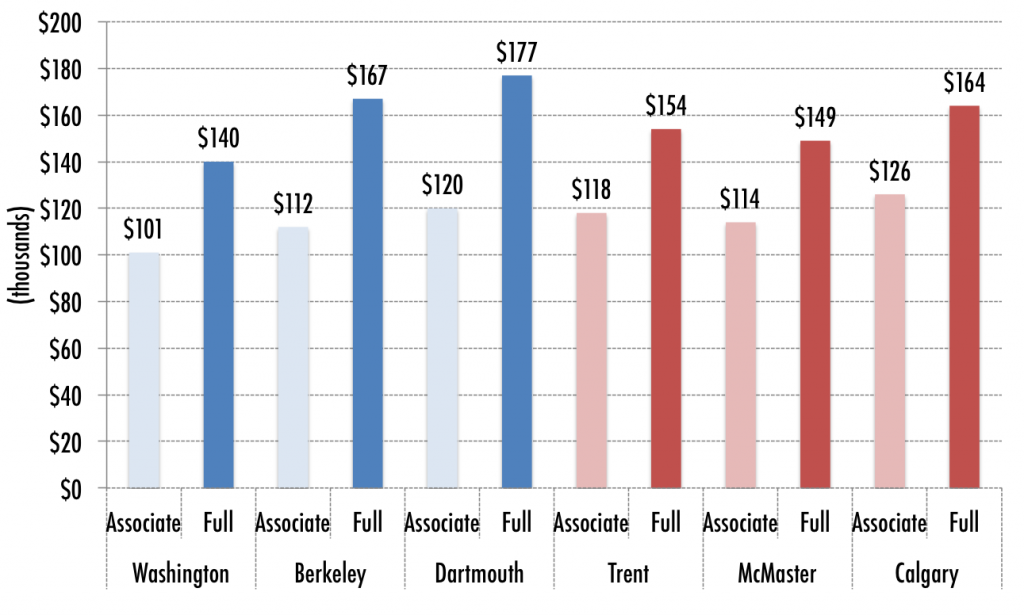

Figure 2: Adjusted Average Base Salaries at Selected Institutions, in Thousands of Dollars.

At the associate professor level, there is still an advantage to being in Canada – Trent, for instance, still has better salaries than Berkeley. But because promotion carries greater rewards in the U.S., the advantage reverses for full professors. There, all three Canadian universities have higher salaries than the University of Washington, but lower than those at Dartmouth and Berkeley.

If we only looked at research-active faculty, the numbers would look even better for the U.S. than they do in Figure 2. On the other hand, if we look at research-inactive faculty, the accurate comparison is Figure 1.

Another way of putting all this is that for older, research-active faculty, Canadian institutions may still face a bit of a compensation gap. For younger (i.e., associate professor rank) research-active faculty, Canada is the better bet; even Trent outspends Berkeley. But where Canada really kicks tail is in research-inactive faculty, where faculty at our three selected universities have a collective compensation advantage of almost 25% for associate professors and 10% for full professors.

Which raises an interesting question: given the choice, is that the category in which we really want to have an advantage?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post