In previous blogs, I discussed how Canadian colleges and universities are generating bad vibes by exacerbating various housing crises. This has been bad for pretty much the entire sector. These strategies have contributed to the impression that the leaders of our post-secondary sector are putting their own institutional interests ahead of the communities they inhabit. It’s not a good look, but for the moment, I think it is survivable from a credibility/responsible neighbour point of view, if only because federal and provincial governments have been moving very quickly on this front to ease rules on housing supply for the past few months.

But there’s a bigger challenge on the horizon with respect to international students: the possibility that Canadians come to the view that international students are actually “crowding out” domestic ones simply because they can pay higher tuition. If that view takes hold – and my sense is that we may not be that far away from it in some parts of the country – things are going to get ugly, fast.

To be clear: I don’t think most institutions are doing this (I’ll get to the exceptions in a second). But the problem is that proving that crowding out is or is not happening is difficult. It is not just the usual challenge that institutions don’t produce enough data to prove much one way or the other; the problem is that there are so many ways to define “crowding out” that even with all the right evidence, it might not be possible to convince everyone. Which is why it is so important to stop the impression getting out in the first place.

If you look at Canadian universities as a whole – or indeed any single institution – one could easily argue that no crowding out is taking place. Sure, the number of international students is increasing significantly. But the number of domestic students is largely stable. International students are paying higher fees, and those higher fees for the most part are going to create new spaces. So, no crowding out, right?

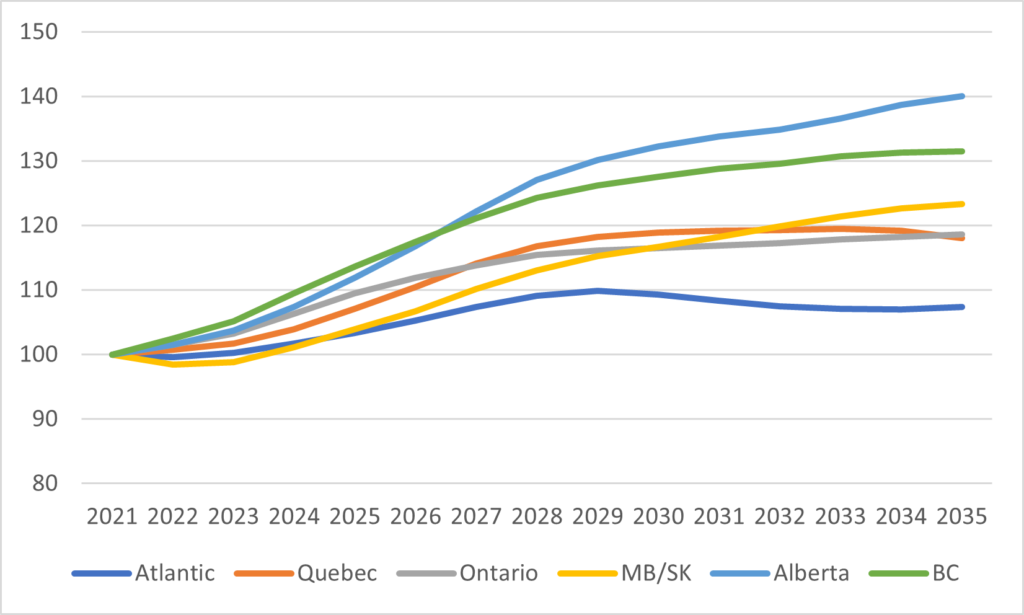

Except: how meaningful is the absolute number of students? That is always dependent to a significant degree on the size of the youth (18-21) population. For instance, if domestic numbers are staying stable but youth numbers are going up – which is precisely the situation we are in right now (see figure below) that is arguably a sign that natural growth is being “crowded out”.

Figure 1: Projected Population Aged 18-21, by Region, 2021-2035 (2021 = 100)

In other words: in theory, every institution in BC and Alberta must see their domestic numbers grow about 30% over the rest of the decade before they can be declared completely innocent of “crowding out”. In other provinces, the figure is lower, but it’s still going to be a daunting task to raise domestic enrolment when the financial incentive to do so is between 4 and 6 times less than it is for international students.

(Except: what if you are one of those schools in a smaller urban area where the local 18-21 population is not slated to make such a recovery? Say, like Laurentian in Sudbury? Then, you can probably allow domestic enrolment to fall or at least stay stable. But you’d better have the numbers to back up your story.)

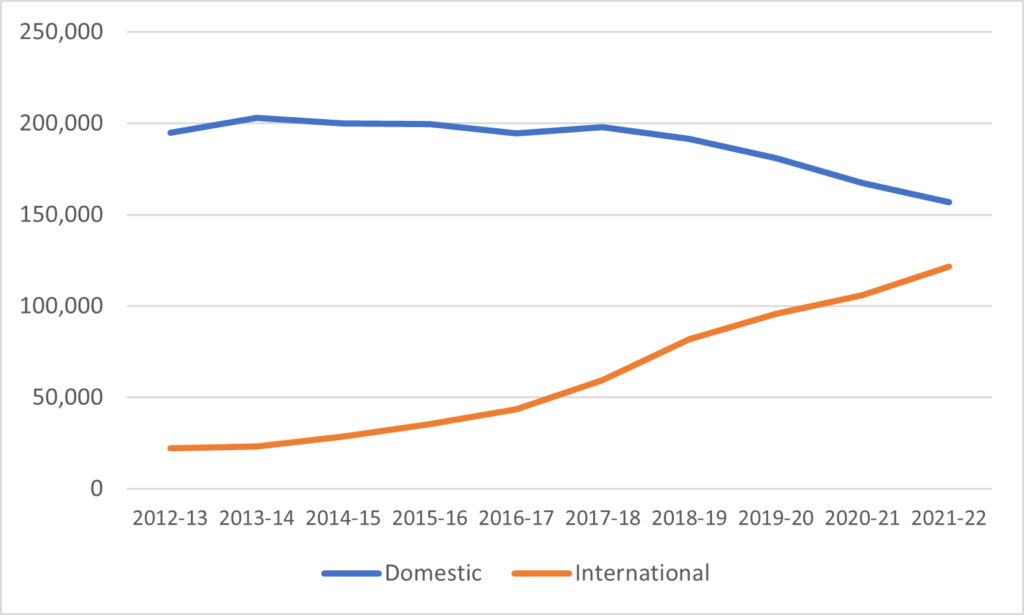

Ah, but wait. We know of a very clear-cut case where international numbers are increasing, and domestic numbers are declining and no one is (yet) screaming blue murder about it. It’s Ontario colleges (data below is for 21-22; everyone in the system tells me the share of international students for 2023-24 over 50% and I am pretty sure at least some of that is due to a fall in domestic numbers).

Figure 2: Domestic v. International Students, Ontario Colleges, 2012-13 to 2021-22

So, if we have such a clear case of international up, domestic down, why aren’t people screaming about unfairness? Many reasons, I suspect, but three stand out. First, it may well be that we are just seeing a decline in domestic demand for sub-baccalaureate degrees, particularly among 18-21 year-olds. This phenomenon has been happening in other countries, and in Ontario it’s been accelerated by the province’s decision to largely shift trades training out of the college sector and into a series of private and union trainers. Second, I’m pretty sure that many Ontario colleges are no longer working as hard to pull in domestic students as they were a decade ago simply because it is so much easier to sign up another thousand students from overseas. But does not recruiting as hard equal “crowding out”? Not obvious. Third and most importantly, with a very few exceptions – say, animation at Sheridan – college programs aren’t especially prestigious. That’s not to say they aren’t good programs, just that carrying them does not carry the kind of prestige as does, say, math at Waterloo or business at Western. And it’s precisely at the program level where angry parents are most likely to train their fire.

You see, people might agree based on the evidence that there is no crowding out at the national level, but at the they might be absolutely convinced that it is happening in significant ways in certain very high-demand programs, say engineering or mathematics/computer science or business. Parents especially are likely to be a lot less forgiving: they don’t care about system-level metrics because what matters is whether their kid gets in to their (prestigious) first-choice program

Disproving crowding out at the program level is pretty difficult. Say your institution has a program with 600 students, one-third of which are international. Now, that program could keep growing along with the local population – faster, even – but if the program is really competitive and only admits half of the students who apply, then the program will have more rejected domestic applicants than it has international students. And that will provoke a lot of questions: to some, that will be prima facie evidence that international students are “crowding out” domestic students.

Now, financially speaking, this argument is almost always nonsense. One less international student rarely means one more domestic student; it just means one less international student and maybe one less domestic student too since international fees, to at least some degree, cross-subsidize domestic spots. But almost no one outside academia understands that and it’s not clear many would care even if they did. My guess is many would prefer smaller, poorer institutions to ones that are seen to favour outsiders.

So – and this is where it gets tricky – the only real defence against claims of crowding out in–demand programs is proof that international students are actually better students than domestic ones. That they got in on merit not because of money. That all things being equal, the weakest international students is still a better prospect academically than the weakest domestic student. If an institution can do that, it has a merit-based defense against crowding out. If an institution cannot do that – and let’s face it, this is not the easiest thing in the world to do given that most institutions in effect have separate admissions systems for domestic and international students – then it’s going to look very much like as if the program/institution is indeed putting foreign dollars ahead of serving the local public.

Can all institutions do this? We’ll see, I guess. One thing I will say is that the current state of data at the program or faculty level at most institutions does not bode well.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

What is wrong with being perfectly honest in your own defence:

“Given that our operating budget from the Province has been reduced by XX percent over the past Y years, we need Z-thousand international students to avoid program cuts and layoffs, and to provide the full suite of services to all our students, including the domestic ones.”

Given the prevalence of the Matthew principle on campi (“For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away”; Matthew 25:29), “crowding out” might happen another way.

Rather than using foreign-student tuition to subsidize underfunded programs, administrators might decide to use it to reinforce success, which is to say, the programs in which foreign students are enrolling. Programs popular with foreign students (marketing, engineering, some sciences) will grow, while those programs which are not popular with foreign students (many languages, historical literatures, Canadian history) will find their budgets stagnate, their retirements not replaced, and eventually their existence threatened. They’ll be crowded out.