A few weeks ago, I was at a session which brought together several folks in the enrollment management business. It was kind of an open-mike session, in which people could bring up topics that seemed most troubling and most in need of addressing. So, the topic turned immediately to the preparedness (or more accurately the lack thereof) of incoming students. Pretty much without exception, from the most to least selective institutions in the room, there was consensus that this was a huge and increasingly disruptive issue, forcing universities to make changes to first and second-year courses to adapt.

Now, my mind went quickly to the effects of COVID. For two years, I’ve been having conversations with folks telling me about how the entering classes of Fall 2021 and Fall 2022 are different from earlier generations. “We’re running remediation within remediation” one Engineering Dean told me. “They don’t know how to work in groups”, said another. A former senior admin returning to a first-year science course for the first time in a while: “The biggest difference? No one asks questions in class anymore”

All of this, of course, maps on to what we all understood the effects of online learning during the pandemic to have been: disastrous in terms of learning outcomes, but also destructive in terms of student study habits: such learning as occurred over video tended to be passive rather than active, and certainly things like group learning were certainly inhibited. So, it’s all down to COVID and school closures, right?

Well, maybe. I’ve been thinking about those conversations a lot over the past few days, ever since the OECD released the latest round of results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Superficially, they provide some backing to this theory. But on greater reflection, I think there’s something much more serious going on, not just in Canada, but in most countries around the world.

Let’s examine PISA itself for a second. It’s a standardized test given to students around the world at the age of 15. For obvious reasons, it’s not a test of knowledge gained from the curriculum; rather it is meant to test how well students can apply their knowledge of reading, math, and science to new problems. Within each participating jurisdiction there is a sampling process both for schools (minimum 150) and individual students (between 4000-8000). If you want to know more on the nature of the tests, you can see the Assessment and Analytic Framework here.

Based on the results, students who take the test get classified from 1-6, from the lowest understanding to the highest. Level 2 is considered “minimum proficiency”. At a jurisdictional level, the collective results of all students are average and “scored” in such a way that it is possible to compare jurisdictions to one another. A score of 500 is equal to the mean score across all test takers in the original 2000 version of the test, when the participating countries were mostly high-income. Since that time, the test has spread to close to 80 countries, and the median national score is down around 440-450. Canada has tended to score above the OECD average in all three areas tested though some of the interprovincial differences are quite large: overall, big provinces do significantly better than small ones. It also does better than the OECD average in terms of equality; that is, to say the rich-poor gap in skills is smaller than it is in many countries.

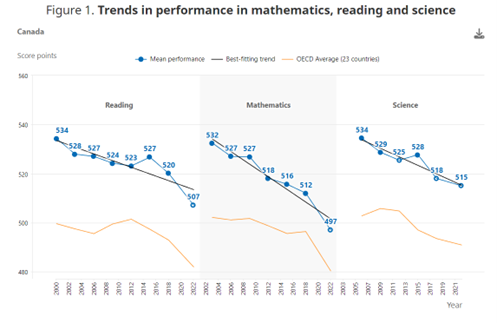

The headline story in Canada is that our average national scores fell enormously between 2018 and 2022: down 15 points in mathematics, 13 points in reading and 3 points in science (the full Canada report from the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada is here and it’s very much worth a read – a brief summary from OECD on Canada is available here). And the rich-poor gap increased somewhat: the fall in scores was more pronounced among students from poorer families than from richer ones. And as I say, that fits with the view that school disruptions were the cause. Case closed?

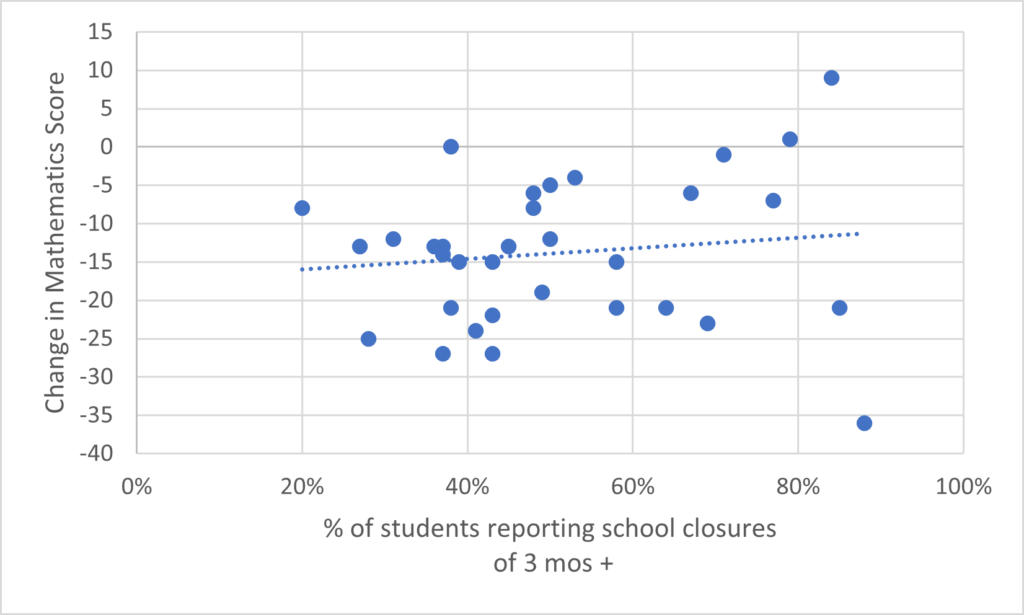

Well, no, not quite. And the reason that’s not the whole story is that Canada is not alone in seeing a drop – virtually every country in the survey saw a drop. But if you look at the drop in scores across jurisdictions, there isn’t a whole lot of correlation between length of time spent in remote learning and the drop in scores. So COVID is part of the story, but not the whole of it by a long shot.

Figure 1: Decline in PISA Scores, 2018 to 2022 vs. % of Students Reporting Long School Closures

The bigger story is this: math and reading scores in Canada – and right across the OECD – have been declining for years. The decline in Canadian scores is happening a little bit faster than in the rest of the OECD but it’s not a huge difference. But what’s interesting to me is when the turn happened. It was right around 2010 – that is, right around the time that smartphones became widespread, a correlation which has also been noted with respect to sharp declines in teenage mental health. Whatever the reason, this decline is something we should all be trying to address. There is no world in which our country’s economic future is made brighter by declining ability in math and reading.

And from the perspective of post-secondary institutions, there is a deeper warning here. I think everyone expected COVID to have a multi-year impact on the preparedness of the couple of cohorts closest to graduation when COVID hit. The more forward-thinking might have thought that these couple of cohorts would have trouble adjusting in a single year or even over the course of an entire degree, which might extend the effects to 5 or 6 years. But the COVID results are telling us is that unless there is some massive remediation going on in secondary schools, the actual damage to post-secondary readiness extends way down in the K-12 system, and is not going to get better for another 4-5 years at the very least.

It’s an interesting question: if universities and colleges wanted to talk to secondary schools about the question of student preparedness, to whom would they speak? Secondary schools are for the most part supposedly in the business of preparing students for further study, but what fora exist to discuss gaps in preparedness? Where are the places where universities and colleges can say to high schools and the ministries that govern them: this isn’t good enough, the students you’re producing simply aren’t ready for work at the post-secondary level.

I am pretty sure some of this happens informally. But formally, in a manner that would actually drive changes in incentives and behaviours? I don’t think they exist. It’s an unfortunately typical manifestation of the Canadian institutions’ inclination towards “I’m OK, you’re OK”. Because, you know, God forbid anyone be held accountable for outcomes.

We could easily be doing better as a country. We just choose not to.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

We know that COVID often causes cognitive damage, and young adults in the first years of COVID faced other stresses (eg. deaths and disability of parents and grandparents and teachers, increased crowding at home, general uncertainty about the future of the pandemic). Stress also worsens cognition.

Due to the vaccinations-only policy infections have been very widespread. While I have no trouble believing that most distance education during the early years of COVID was poorly done, or that smartphones and social media increase anxiety and distraction, shouldn’t the direct effects of COVID be in there somewhere?

Alex, you correctly note that…..”But what’s interesting to me is when the turn happened. It was right around 2010 – that is, right around the time that smartphones became widespread, a correlation which has also been noted with respect to sharp declines in teenage mental health. Whatever the reason, this decline is something we should all be trying to address.”

Buried deep in the PISA report on Canada is this statistic: ” about 21% of students in Canada reported that they cannot work well in most or all lessons (OECD average: 23%); 29% of students do not listen to what the teacher says (OECD average: 30%); 43% of students get distracted using digital devices (OECD average: 30%); and 33% get distracted by other students who are using digital devices (OECD average: 25%). On average across OECD countries, students were less likely to report getting distracted using digital devices when the use of cell phones on school premises is banned.

It appears that a very significant percentage of middle-school and high-school teachers have given up on controlling the use of cell phones in their classrooms, and the students’ responses above speak to the detrimental effects. I don’t know if anyone in a position of power has the courage to address this and ban the use of cell phones on school premises.

I’d be interested in whether the standard deviations on the PISA scores have changed. My own sense is that Covid lockdowns affected different people differently. This isn’t just a matter of wealth — some people flourish while working alone. The kind of good students who do the reading, and look up anything they don’t understand in wikipedia or Khan Academy were given their heads, while the kind of bad students who do the minimum amount of work and remain basically incurious found they could just watch Netflix all day.

Moreover, some forms of instruction could be transferred better (or at least, less badly) to Zoom. I wonder, for instance, whether sudden drops in Finland show that the relatively unstructured form of Finnish learning just didn’t translate, whereas the rote learning and relentless practice favoured by some Asian societies translated quite well.

This also ties in with the sudden ubiquity of cell phones: give a cell phone to a curious student, and they’ll use it to look up youtube videos and wikipedia articles for history class. Give it to an incurious student and they’ll watch TicToc videos. Hence my interest in the standard deviation.