One of the most annoying things about the last couple of weeks – apart from the general collapse of civilization – has been everyone and their dog claiming they are “moving classes online”. I really wish we had found another word for this, because if there is one thing universities and colleges are NOT doing, it is transitioning to online education.

It must be especially galling if you’re, say, at Athabasca University and produce real, high-quality online content all the time. It takes time to learn how to teach online effectively – it’s not an instantly transferable skill. Developing effective online learning resources isn’t something that can happen overnight either. Universities that are good at online instruction takes years (and millions of dollars) to get good at it. And then all of a sudden, with no preparation whatsoever, every university and college in the country claims it, too, is online. This is, as my colleague Kevin Carey explains in much more detail in an excellent New York Times article, is a more than a bit of an insult to people who do this stuff for a living.

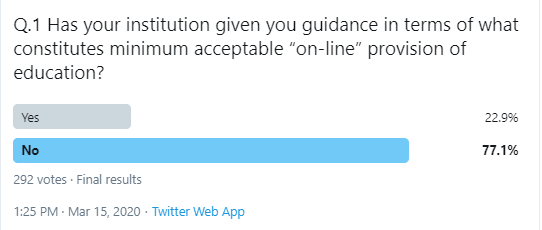

Over Sunday, I decided to do a little 24-hour twitter poll of Canadian professors/instructors, to see what “moving online” actually consisted of (yes, it’s a twitter poll so scientific validity is nil, but I suspect there is wisdom in here nonetheless). I started by asking about whether their institutions had given any guidelines about what constituted minimum acceptable “on-line” provision of education. Three-quarters said no.

At the time I asked my question, the order to go on-line had already dropped at most institutions. But, clearly, it hadn’t been accompanied by much guidance about what that meant. In some cases, this was deliberate (as I noted yesterday, some schools are taking a two-to-five day pause before “moving classes online”). This isn’t a criticism – everyone is just doing the best they can to stumble over the end-of-term finish-line in April – but it does suggest that in the rush to suspend in-person classes, professors have mostly been left to fend for themselves as far as pedagogy is concerned.

(One might argue that Canadian universities aren’t very good at enunciating standards of in-class education either and so this is just status-quo, but we’ll leave that for now).

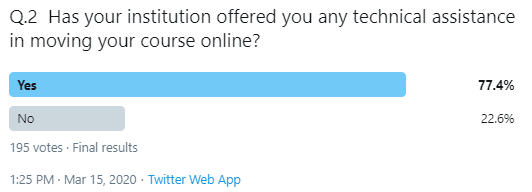

Question 2 asked a slightly different question: did your institution provide any technical assistance in moving courses online? The answer here was better: roughly seven out of ten said they had received such assistance.

(Of course, this assistance may just have been a pdf telling you how to turn on Zoom or a page with a bunch of links. And they may not have thorough concerning what kind of bandwidth was necessary to run loads of such courses simultaneously. But on the other hand, from what I’ve seen/heard, most people are getting more advice from peer networks than from institutions anyway – there is a lot of local expertise available, should people want to tap it.)

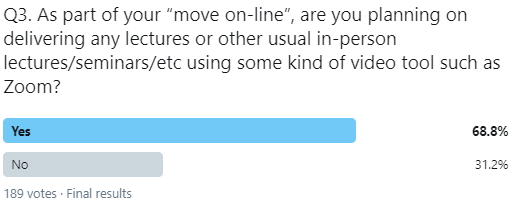

Question 3 was, to my mind, the big one. I asked profs if they were planning on moving their usual in-person teaching activities – lectures, seminars, etc – online. Nearly a third said no. As in, flat out, “move online” in a third of cases means basically, the class wrapped up for the year.

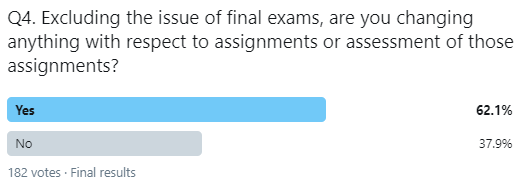

Similarly, in question 4, about a third of respondents said they were not changing anything with respect to assignments and assessments. I suspect this is more or less the same third that said they were not teaching online, but I can’t prove that because twitter polls only provide aggregates.

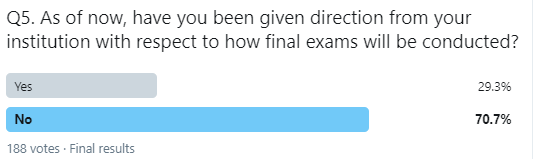

In question 5, I asked people if they had been given any news about what would happen to final exams. A remarkable 70% said their institution had not communicated any decisions about finals. I think this is evidence that as of Friday, a lot of institutions thought they could kick the can down the road on this issue. “Maybe we’ll be back up by then”, they thought, “finals aren’t for a couple of weeks, we can delay the decision for a bit.”. This is, unfortunately, magical thinking. “Coming back”, in the sense of getting students together in rooms for the purpose of instruction or testing, is months away. Institutions should face up to it quickly.

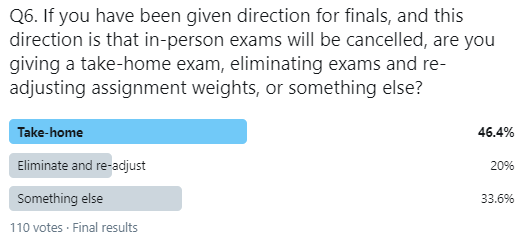

Finally, in question 6 I asked profs what contingency plans they were making for finals, and the most common answer was “make the final a take-home”

The upshot of all this is that the so-called “move online” is not, in fact, a move to online education. Online education is a serious and long-term development. What this is, for the most part, is a wing-and-a-prayer, duct-taped, please-just-let-us-get-to-the-end-of-the-semester DIY job. This is why many of the hot takes about this crisis being a big deal for online learning, such as this one, are nonsense, and true only if you attach no specific meaning to the words “online”, “perfect”, “measure” or “learn”.

Stay safe, everyone.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I was chatting with my wife about what she was going to do with the instruction to go online. She and her lab instructors are looking into Skype/FaceTime, etc. to replace office hours. She’s quite proficient with Moodle, so she can put in some lecture material with associated videos, as well as develop assignments and tests. So the tech isn’t necessarily the problem from her end as long as the system doesn’t crash from overload. However, she has about 150 students in her class, almost all of them in the new cohort of international students from India. She noted that the majority of them don’t have their own laptops or desktop computers; they use their phones when not in the university’s computer labs, or share one laptop in a household. Moodle’s doable on some phones, but not ideal. This brings up the issue that I haven’t seen discussed much in all the talk to go online: the ability of students to access and take up the material effectively. I hope that can make it into the planning as we get past this initial panic.