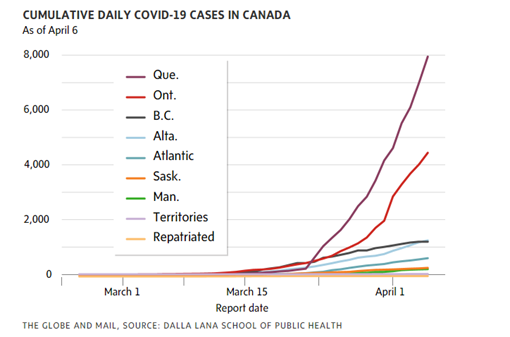

Though the national media has dealt gingerly with the subject, the fact is that this pandemic is playing out very differently across the country. Ontario and Quebec are still in full-on holy crap mode: the situation is bad, no two ways about it. Not Italy bad, but bad enough. But away from Central Canada, it’s a very different story, as this graph from Tuesday’s Globe and Mail shows.

Look at BC, where despite proximity to the early outbreak hub of Seattle, new daily cases seem to have been contained at under 100 cases. Look at the three Maritime provinces, which as of Wednesday AM had only a single death between them. Even Alberta, which had one of the country’s earliest mass transmission events (a physicians-only bonspiel, which has to be up there in the running for “most Canadian pandemic event ever”), hasn’t done too badly, although there has been an uptick in recent days.

At one level this does not matter much: at a personal level, we’re all equally vulnerable to the virus. But at another level, it really does, because on current trends, it looks like most of the country is going to exit from physical distancing measures a lot faster than central Canada. And then some very interesting politics are going to play out.

Just to take a few examples:

The CIHR recently decided – on highly debatable grounds – to cancel its Spring funding competition in order to devote that money to COVID-related causes, a move that will have strong negative consequences for younger researchers. Quite apart from the fact that CIHR is undoing most of its recent good work in retreating from its (roughly) 2007-2017 policies where it consistently and wrong-headedly emphasized translational over basic research: how is this going to look in four months time in, say, British Columbia where the disease may already be under control? Why should their young researchers get sacrificed for a disease which may not be as grave an issue there?

What happens if universities in eight provinces are open for face-to-face teaching in September but not in Ontario and Quebec? More specifically, how do federal rules on granting student visas and permitting students to enter the country evolve? Do BC institutions lose out on a billion dollars or more in income just because Quebec’s Bill 21 leaves Quebec vulnerable to disease outbreaks because of the way it inhibits mask-wearing?

You can see where this might get ugly.

But, you say: aren’t we all in this together? Aren’t we one country with freedom of movement and so, like an old-style naval convoy, we have to go at the pace of the slowest ship? Well, no. That ship sailed a while ago (so to speak). Quebec, New Brunswick, PEI and the three territories have already to some degree introduced various types of internal border controls. If every province introduces those kinds of controls, it would be hard to argue against the “cured” provinces being able to admit students from abroad.

I don’t know how serious these problems are going to end up being. The country has pulled together pretty well during this crisis so far. I’m just saying that it’s a big country, external shocks can play out very differently in different parts of the country, and that can make it very difficult to make national policy in ways that don’t seem blatantly unfair to at least one or two provinces. Normal politics might be suspended in March and April, but don’t count on that lasting right through to the end of the emergency.

Shout-out to my friend & colleague Andrew Potter for convincing me that virus federalism might actually be a thing. If you aren’t already subscribing to the daily Policy for Pandemics blog he edits for the Max Bell Policy School, what are you waiting for?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post