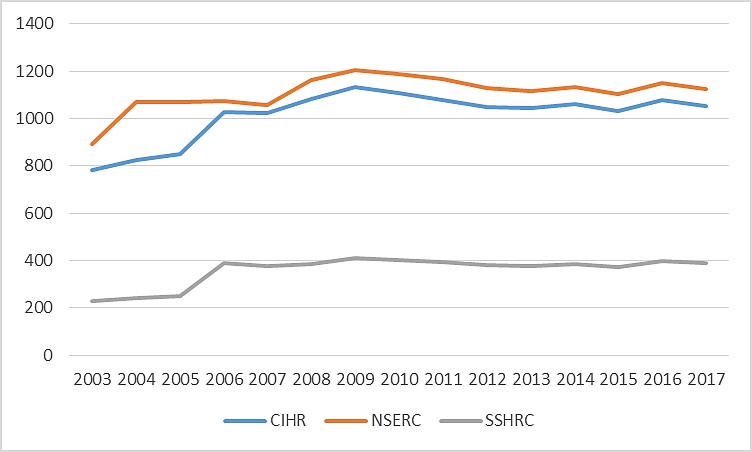

Every year on budget night, we at HESA Towers publish a graph tracking granting council expenditures in real dollars. This year it looks like this:

Tri-council Funding Envelopes

Some people really like the graph and pass it around and re-tweet it because it shows that whatever governments say about their love for science and innovation, it’s not showing up in budgets. Others (hi Nassif!) dislike it because it doesn’t do justice to how badly researchers are faring under the current environment. Now, these critics have a point, but I think some of the criticism misunderstands why government funds research in the first place.

The critique of that graph usually makes some combination of the following points:

- Enrolments have gone way up over the past fifteen years, so there are more profs and hence more people needing research grants.

- At some councils, at least, the average grant size is increasing, sometimes quite significantly. That’s good for those who get grants, but it means the actual number of awards is decreasing at the same time as the number of people applying is increasing.

- In addition to an increasing number of applicants, the number of applications per applicant also seems to be increasing, presumably as a rational response to increasing competition (two lottery tickets are better than one!).

Now, from the point of view of researchers, what all this means is that “steady funding in real dollars” is irrelevant. On the ground, faculty are having to spend more time on grant proposals, for fear of not receiving one. The proportion receiving awards is falling, which has an effect on scientific progression, particularly when it happens to younger faculty. So it’s easy to see why the situation has academic scientists in a panic, and why they’d prefer a graph that somehow shows how applicant prospects of receiving grants are nosediving. And that graph would as be as undeniably true as the one we publish.

But, from the perspective of Ottawa, I think the answer might well be: “not our problem”.

Here’s why. The main reason governments get into the research game is to solve a market failure. The private sector can’t capture all the benefits of basic research because of spillovers, so they underinvest in it. Therefore, governments invest to fill the gap. This has been standard economic theory for over 50 years now.

So, to be blunt, government is there to buy a particular amount of science that is in the public interest given corporate underinvestment. It is not there to provide funds so that the academic career ladder works smoothly.

Provinces and universities decided to hire more science profs to deal with a big increase in access? Great! But did anyone ask the feds if they’d be prepared to backstop those decisions with more granting council funds? Nope. They just assumed the taps would keep flowing. Academia decided to change the rules of pay and promotion in such a way that emphasized research, thus creating huge new demand for more research dollars. Fantastic! But did anyone ask the feds to see how they’d cope with the extra demand? Nope. Just hope for the best.

There’s a case, of course, to say that the federal government, via the granting councils, should be more concerned than it is with the national pipeline for scientific talent. What’s happening right now could really cause a lot of good young scientists to either flee their careers or their country (or both), and that’s simply a waste of expensively-produced talent. But for the feds to thoroughly get into the business of national science planning requires provinces and institutions to give the councils a more direct role in institutional hiring decisions and the setting of tenure standards. I bet I can guess how most people would feel about that idea.

So could the government put more money into granting councils? Sure. Could some councils make things better by reversing their Harper-era decisions to go with larger average grant sizes? Yes, obviously. But let’s remember that at least part of the problem is that institutions and academics have taken a lot of decisions over the past twenty years about what research and scientific careers should look like with very little thought to the macro fiscal implications, under the assumption that the feds and the councils would be there to bail them out.

That needs to change, too.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I remember thinking about the science/engineering funding problem when I first started my faculty position in 1997 (esp. in the context of a institute that recently received University status) – and was influenced by these articles by professor Goodstein which I would recommend people to read (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Goodstein):

http://authors.library.caltech.edu/50907/1/eost11547.pdf

http://authors.library.caltech.edu/62996/1/S0883769400045231a.pdf

I agree with his assessment, 20 yrs later:

“For science to survive, we must find a

radically different social structure to orga-

nize research and education in science

after the Big Crunch. The new structure

will come about by evolution rather than

design because, for one thing, neither I

nor anyone else has the faintest idea of

what it will tum out to be, and for anoth-

er, even if we did know where we are

going to end up, we scientists have never

been very good at guiding our own des-

tiny.”

Anyone who wants to look up SSHRC’s program success rates can go here:

http://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/results-resultats/stats-statistiques/index-eng.aspx

There are easy-to-use drop boxes from which you can download Excel files for each program for each competition.

Anyone who wants to look up NSERC’s program success rates can go here:

http://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/Professors-Professeurs/DiscoveryGrants-SubventionsDecouverte/Index_eng.asp

For NSERC, you’ll have to go through the list and find the specific year you want to investigate. The list only has statistics on Discovery Grants and RTIs. For other programs, you’ll have to check with NSERC.

Grants success is increasingly used to measure the strength of humanities programs, also, and even individual humanities researchers. It’s hard to imagine a more thorough confusion of cost and value.

This is peculiarly perverse in that whereas much of our work isn’t expensive, and certainly doesn’t form some sort of giant project, that’s increasingly what’s funded. A demand that we apply for funding is a demand that we pervert our research into something fundable.

I think this is a good analysis. It highlights that a lot of factors have contributed to perverse incentive systems and the concentration of research dollars in fewer and fewer hands. Not sure where you are going with the last paragraph however. In what ways ought/would an institution influence or think strategically about “macro fiscal implications?”

This graph would be much better with a indication of what the y-axis refers to. ‘Real Dollars’ in text only goes so far. 1000 million? 1000 awards?