One of the fastest ways to get into an argument at a university is to suggest that there is some necessary trade-off between research and teaching. Really. The words will hardly be out of our mouth before someone comes charging at you, claiming the opposite. It’s not an empirical argument or anything, but an article of faith. Frankly, you wouldn’t want it to be an empirically testable position because if it was, someone might start asking some pretty difficult questions.

There have been attempts to quantify this relationship but these attempts are not super-high quality mainly because there are multiple possible different measurements of “research” and “teaching quality” and in the case of the latter, measures are neither plentiful not uncontested. Not surprisingly then, studies come up with wildly different correlations depending on (among other things) the methodology used. The last reasonably broad synthesis of data that I know of was done about fifteen years ago in the UK by the Department of Education and Skills (available here), which reviews a very large number of studies. It notes that most studies suffered from deep methodological challenges and inconsistencies which, even if you accepted each of them as valid, makes a nonsense of most meta-analyses. That said, the review found that the preponderance of studies showed either a null or positive relationship, and that the average relationship was very modestly positive, at about 0.1.

I mean, I suppose you could call that a victory for the “no trade-off” position. But you’d have to be straining pretty hard to do so.

The thing is, even if there are some complementarities between research and teaching, there are still hard trade-offs. Time, for instance. An hour in the laboratory or the archives is an hour not spent on pedagogy. So yes, an hour of research might improve teaching, but does it improve it as much as a more direct application of talent to the task at hand? Or, take money. Being a serious research university requires you to spend tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars every year in construction and maintenance of laboratories. That’s money an institution is not spending on shrinking class sizes. Is all that money worth your (methodologically suspect) 0.1 correlation?

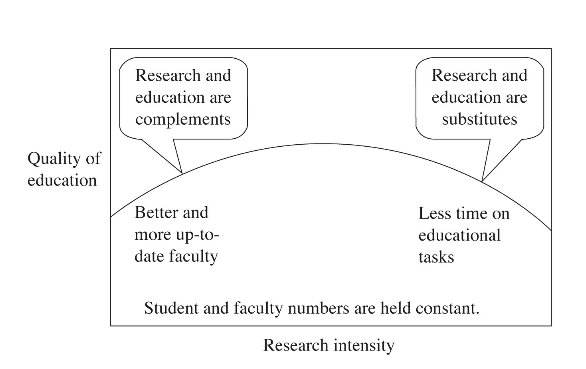

And then there is the fact that the actual relationship between teaching and research is probably non-linear. Below is a graph produced by William Massy, one of the giants in the field of economics of education. It’s a sensible way of visually suggesting the relationship between teaching and research at the institutional level – up to a certain point, they are complentary, but beyond it they are substitutes. This is, I think, a pretty accurate way to describe things, and it mostly works at the level of the individual faculty member, too.

In fact, this is such a reasonable depiction of the true relationship between teaching and research I suspect the no-trade-off crew would probably agree with it as well. And in fact, therefore, what I suspect the no-trade-off crew is saying when it rages against trade-offs is “we here at institution X are at the apex of this curve”. And maybe that’s true.

But how would they know, exactly?

I mean, look, if being at the apex was really a priority, then deans and department heads would be managing staff to make sure that on aggregate, the balance between research and teaching was at the apex and not too far to one side or the other. And provosts would be managing faculties to reach an institution-wide apex. And Ministries or an intermediary body would be managing across institutions to achieve a system-wide apex. But of course, no one does this. No one. What we have instead is a system where nearly all the status and financial rewards are on the research side, and so there is a perpetual race to the right side of the curve, all the while claiming that there is no trade-off even though it is almost certainly the case that at some places the apex point is a long way in the rear-view mirror.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thanx for this.

A crucial variable is the examination of the relation between teaching and research by level of actor – individual academic, department, faculty, institution, sector, province/state, country, and world.

Another crucial variable is the level of analysis by breadth of activity – sub discipline, discipline, field, area, broad area.

I think the figure is from Massy, William F (2003: 97) Figure. Teaching and research: Complements or substitutes? In Honoring the trust: Quality and cost containment in higher education. Anker Publishing Company.

It was republished in Massy, William F (2016: 45) Figure2.1. Teaching and research: Complements or substitutes? In Reengineering the university: How to be mission centered, market smart, and margin conscious. JHU Press.

Thanks for the post.

As one of my colleagues is fond of saying, time is brittle. The trade-off is real, and I infer from the figure you show from Massy that research engagement is supposed to lead to “Better and more up-to-date faculty”. “Up-to-date” how broadly? In my narrow sub-specialty, yes (hopefully!). In the breadth I need for an undergraduate course? Not from engagement in research by itself. Others experiences will undoubtedly differ – the plural of anecdote is still not “data”.

Of course the relationship between teaching and research isn’t empirically provable. You obviously can’t prove a platonic ideal. It’s not that everyone is afraid of what they’ll find — it’s just that they correctly identify any attempt to draw a correlation as a category error.

Let’s put it this way — if you don’t want experts to teach and teachers to be experts, you simply don’t want a university in the first place. You just want a high school, maybe with a research centre attached, or a research centre, maybe with a training institution attached. This is why all-teaching and all-research positions aren’t just bad policy for universities: to create them is to enact a policy of not being universities.

Nevertheless, Massy’s (apparently freehand) graph makes a point: the extremes are where the complementary of teaching and research break down. And this is where each is “excellent.” A call for “excellent pedagogy” is usually accompanied by a call to stop wasting time on cultivating research expertise, just as, as you note, placing all the status and rewards on “excellent research” skews everything to the other side.

More management would be constitutively incapable of moving us back to the middle. It would just enslave us to the metrics that can measure only either teaching or research (assuming, that is, that they measure anything at all). It would skew us towards both extremes at once, and further separate teaching and research, undermining the university as such.